Camelopardalid Meteor Shower

Credit: Gail Lamm

A small Camelopardalid meteor streaks through the northern lights as the Milky Way shines overhead in this stunning photo by stargazer Gail Lamm from Balmoral, Manitoba in Canada on May 24, 2014.

Credit: Malcolm Park via the Virtual Telescope Project

A brilliant meteor streaks over Toronto, Canada in this photo by Malcolm Park shared by the photographer and VirtualTelescope Project during the Camelopardalid meteor shower created by Comet 209P/LINEAR early on May 24, 2014.

Credit: BG Boyd

Photographer BG Boyd captured this photo of a meteor from the Camelopardalid meteor shower over Tucson, Arizona early on May 24, 2014. The meteor display was created by dust from Comet 209P/LINEAR.

space.com

space.com

The Night Sky

Credit: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope/Coelum

Friday, May 30, 2014: Stars form within nebula NGC 2170, which lies in the constellation of Monoceros (The Unicorn). A dark nebula, such as this one, provides raw material for the star formation going on inside them. The newly formed, massive blue stars seen here continue to push away traces of the dust that previously hid them from view. The material that remains will eventually disperse in the interstellar medium. ~Tom Chao

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA; Acknowledgement: Nick Rose

Wednesday, April 16, 2014: Spiral galaxy NGC 3455 lies roughly 65 million light-years away from us in the constellation of Leo (The Lion). NGC 3455 falls into the category of type SB galaxy — a barred spiral — in the Hubble classification system, the Hubble Sequence. Galaxies of this type appear to have a bar of stars slicing through the bulge of stars in their centers. Further, this galaxy is considered a SBb type, which means its spiral arms neither wind tightly nor loosely. NGC 3455 makes up a pair of galaxies with its partner, NGC 3454 (out of frame). This cosmic duo belong to the NGC 3370 group.

The Orion Nebula, also known as Messier 42 or NGC 1976, is located approximately 1,500 light-years from Earth. Miguel Claro took the photo in Serra de Aire, Portugal near the Mira de Aire Caves complex. He used a portable Vixen Polarie Star Tracker Mount with a Canon 60Da camera and Astro Professional ED 80 telescope to capture the image, which was released to Space.com on Feb. 7, 2014.

Credit: Miguel Claro | www.miguelclaro.com

Credit: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope/Coelum

Tuesday, April 1, 2014: These four spiral galaxies in NGC 4410 display an extraordinary cosmic spectacle, each generating immense tidal forces that rip each other apart as they pass close to each other. The galactic disks and spiral arms stretch apart while stellar filaments swirl into the intergalactic medium as the galaxies entwine in a dance of staggering proportions. ~Tom Chao

The Swan Nebula (M17), where ultraviolet radiation streaming from young hot stars sculpts a dense region of dust and gas. M17 is some 5,200 light-years from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius and is one of the most massive and luminous star-forming regions in our galaxy

Photograph: Gemini Observatory/AURA

On the left, surrounded by blue spiral arms, is spiral galaxy M81. On the right marked by red gas and dust clouds, is irregular galaxy M82. This stunning vista shows these two mammoth galaxies locked in gravitational combat, as they have been for the past billion years. The gravity from each galaxy dramatically affects the other during each hundred million-year pass. Last go-round, M82's gravity likely raised density waves rippling around M81, resulting in the richness of M81's spiral arms. But M81 left M82 with violent star forming regions and colliding gas clouds so energetic the galaxy glows in X-rays.

Credit: Rainer Zmaritsch & Alexander Gross

Robert Fields sent Space.com this image of Messier 42, or the Orion Nebula on March 18, 2014. The image is a compilation of narrowband data in SII, HA and OIII taken from Irvington Observatory of Howell Twp, Miss.

Credit: Robert Fields

The Pleiades star cluster (M45) is a group of 800 stars formed about 100 million years ago. The cluster is located 410 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Taurus.

Credit: Chuck Manges | www.astrochuck.blogspot.com

A. Garrett Evans sent Space.com this 9-shot panorama of the Milky Way rising over Cape Neddick Lighthouse in York, Maine on March 3, 2014. The photo covers nearly 180 degrees and was taken with a Canon 6D camera, Canon 16-35mm @ 16mm, ISO 4000, f/2.8, 30 sec.

Seen here is a jaw-dropping, amazing, stunning panorama that includes several of the most famous night sky objects, Orion's Belt and the surrounding molecular cloud. What could possibly be said to capture the sheer incredibleness of this image that isn't conveyed simply by looking at it?

First of all, to set the scene, we're looking at the three stars in Orion's Belt, Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka, seen at left in the image. Just below Alnitak is the extremely recognizable Horsehead Nebula. Over on the right of the image is the gorgeous Orion's Nebula, visible to the naked eye as the middle star in Orion's sword. Both nebulas and the surrounding gas and dust are among the hottest regions of star formation that can be seen in the night sky. All of these objects have been studied for centuries, yielding insight in modern times into the life cycles of stars.

This beautiful vista was created by Australian astrophotographer Terry Hancock. The data were captured in January, February and early March 2014 over eight nights from Hancock's home in Fremont, Michigan. Check out more of his work on his Flickr page.

Green airglow shimmers atop translucent clouds as the Milky Way rises over a remote island off the northwest coast of Africa in a majestic photo recently sent to Space.com. Credit: project nightflight

Randy Halverson dakotalapse.com captured the footage from April-Nov 2013 in South Dakota, Utah and Wyoming. 2 Canon 5D Mark III and 1 Canon 6D cameras were used to create this.

Astrophotographer Ken Crawford sent Space.com this image of galaxy NGC 2685, also known as Arp 336, on March 4, 2014. He captured the image from Rancho Del Sol Observatory in Rancho Del Sol Camino, Calif.

Astrophotographer Garry Owens sent in a photo of the recent brilliant auroral display seen in the United Kingdom. He took the shot on Feb. 27, 2014, in Prestatyn, Wales, UK.

Astrophotographer Terry Hancock sent Space.com this wide field image of a few galaxies in the constellation Coma Berencies on March 2, 2014. He captured the photo from Fremont, Mich. on Feb. 22 and 27, 2014.

Comet 209P/LINEAR

A meteor streaks through the night sky above Yellowstone National Park on Halloween 2008.

Photo Credit: Jeffrey Berkes

New Meteor Shower: How to Hear the Shooting Stars

On the night of May 23-24, 2014, a new meteor shower from the Comet 209P/LINEAR will light up the night sky. It could even spark a "meteor storm," or it could fizzle out.

Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

A rare meteor storm, or especially intense meteor shower, could happen if a particular comet was active hundreds of years ago.

Credit: By Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

A brand new meteor shower shooting 100 and potentially as many as 400 meteors an hour may radiate from the dim constellation Camelopardalis below the North Star Saturday morning May 24. Each is crumb or pebble of debris lost by 209P/LINEAR during earlier cycles around the sun. This map shows the sky facing north around 2 a.m. from the Saturday May 24 from the central U.S. Stellarium

Photo Credit: Jeffrey Berkes

New Meteor Shower: How to Hear the Shooting Stars

By Joe Rao, Space.com Skywatching Columnist | May 20, 2014 03:07pm ET

Comet 209P/LINEAR may create a new meteor shower on May 23-24, 2014.

Credit: NASA/JPL

Even if cloudy skies or bright city lights hamper your ability to see the much-anticipated meteor shower this weekend, you can still listen to it on the radio.

On Friday night and early Saturday morning (May 23-24), Earth will plow through debris shed over the years by Comet 209P/LINEAR. The result likely will be a new meteor shower, and possibly a spectacular meteor storm of 1,000 or so shooting stars per hour, experts say.

Under certain conditions, meteors can reflect radio waves in the same way that the ionosphere — a portion of Earth's upper atmosphere — propagates transmissions between widely separated ham-radio operators. The ionosphere usually reflects frequencies below 30 megahertz (MHz), but it's transparent to higher frequencies, such as the FM broadcast band (88 to 108 MHz).

Such high-frequency (short-wavelength) radio signals generally pass unimpeded through Earth's atmosphere in straight lines; they cannot follow the curvature of the Earth to reach a listener beyond the horizon. Yet when certain layers of the upper atmosphere become ionized, they can reflect the signals back to the ground far away. The lowest such layer, 60 to 70 miles (96 to 112 kilometers) up, is called the "E layer" of the ionosphere — and that's the altitude where the majority of meteors are seen.

So, when a meteoroid vaporizes as it passes through the atmosphere, it briefly ionizes air molecules along its path. Forming an expanding column or cylinder several miles or more in length, these ions can scatter and reflect radio waves, in much the same way that jet contrails scatter sunlight, leaving a glowing trail in the darkening sky after sunset. But because the ion trails disperse rapidly, the reflected radio waves generally last for only a few seconds.

Tiny particles tend to vaporize at the bottom of the E layer. Large particles, in contrast, begin to flame higher up. And predictions for the particles shed from Comet 209P/LINEAR suggest that most of them will be large. Such meteors produce longer-lasting ionization, and since they start to "flame on" higher up, they can reflect signals from more distant transmitters.

On the ground, a meteor's appearance is signaled by the momentary enhancement of FM reception from a distant station.

For this to work, find a frequency where no nearby FM station is broadcasting. You'll have the best chance of success by scanning the low-frequency end of the FM band, below 91.1 MHz.

Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Why there?

The low end of the FM dial is where the lower-power stations, chiefly run by colleges and universities, are found, and they're usually free from local interference from high-power commercial stations.

In fact, unless you live in a very unpopulated region of the country, your chances of finding an open frequency free of interference above 91.1 MHz is rather small. Therefore, you should tune to a distant station on a clear frequency below 91.1 MHz.

The FM Atlas, which was published from 1970 to 2010, provided listings of all FM stations in North America, with the unique feature of frequency-by-frequency maps. Bruce Elving, publisher of the FM Atlas, was an expert in all things FM. Elving passed away in 2011, but as a tribute to his love of and dedication to FM radio, the 21st and final edition (2010) is freely available courtesy of AmericanRadioHistory.com. http://www.americanradiohistory.com/Archive-FM-Atlas/FM-Atlas-21-2010.pdf

On the same site, you can also view a complete listing of AM and FM stations from the 2010-2011 edition of the M Street Directory: http://www.americanradiohistory.com/Archive-M-Street/2010/Freq-M-Street-19-2010-2011.pdf

Credit: By Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

What are you listening for?

Normally, you will just hear a hiss of noise when you're tuned in to an "empty" radio frequency, but as meteors zip in through the atmosphere, a distant, silent station will abruptly "boom in" for anywhere from a fraction of a second to perhaps several seconds. You might also hear what initially sounds like a "pop" or whistle, and then, as the ionization trail dissipates, the station will quickly fade away.

Because of their height, meteors best reflect signals from stations 800 to 1,300 miles (1,300 to 2,100 km) from you.

The best time to listen is when the radiant — the spot from which the meteor shower appears to originate — is 45 degrees above the horizon, as seen from a point midway between you and the transmitter. (Your outstretched fist held at arm's length measures about 10 degrees.)

At the predicted peak time for Saturday morning's potential meteor outburst, the U.S. Pacific Northwest and southern Canada will see the radiant close to that preferred altitude, whereas New York, Chicago, Denver and Los Angeles will not be far behind, at about 30 degrees. [How Meteor Showers Work (Infographic)]

Also, it is best to tune to a station located in a direction that is perpendicular to the radiant. Since the 209P/LINEAR radiant will be toward the northern part of the sky, the better listening directions will be to the west and east of you. (The possible new meteor shower should appear to radiate from a point near Polaris, the North Star, which lies at the end of the handle of the Little Dipper.)

Most meteors are heard but not seen

If you are watching for meteors while monitoring your radio, most of the time, you will hear a "ping" of reception but won't see a corresponding meteor streak in the night sky.

Recall that most of the meteors you're "hearing" are roughly halfway between you and the radio station, about 400 to 650 miles (650 to 1,050 km) away, so they are occurring either near the horizon or just below it.

Back in the 1970s, members of the Nippon Meteor Society in Japan who made extensive records of radio meteors noted that only 20 to 40 percent of radio meteors were simultaneously observed visually.

What if you can't find a clear frequency?

It may be difficult to find a clear or empty FM frequency on the radio dial, especially if you live in large metropolitan or urbanized areas.

In many ways, finding a clear frequency seems to go hand in hand with trying to find a dark sky free of light pollution; you'll probably have a much better chance in rural or country locations. But if you can't find an FM frequency to work with, don't despair. You can still listen for meteors on Space Weather Radio.

Radio engineer Stan Nelson uses a Yagi antenna in New Mexico to detect 54-MHz TV signals reflected from meteor trails. When a meteor passes over his observatory — ping! — there is an echo. It's the next best thing to a giant government radar!

For more details, visit spaceweatherradio.com.

Good luck, and good listening!

Eta Aquarid Meteor Shower

Image credit: Kevin Cole

Meteor Shower Spawned by Halley's Comet Peaks This Week

By Joe Rao, Space.com

Early Tuesday morning (May 6), just before dawn begins to light up the eastern sky, stargazers have an opportunity to see a meteor shower made up of debris from one of the most famous of comets in history: Halley's Comet.

Halley's Comet made its last pass through the inner solar system in 1986 and it's not due back until the summer of 2061. Nonetheless, each time Halley sweeps around the sun, it leaves behind a dusty trail — call it "cosmic litter" — that ends up trailing behind the comet.

And as it turns out, the orbit of Halley's Comet closely approaches the Earth's orbit at two places. The first point comes now, in early May, producing the Eta Aquarid meteor shower. The other point occurs in the middle to latter part of October, producing a meteor display known as the Orionid meteor shower.

You can watch live webcasts of the Eta Aquarid meteor shower from the Slooh community telescope beginning at 9 p.m. EDT (0100 May 6 GMT)

This year, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower is predicted to peak early on Tuesday morning, May 6, but will also be visible late at Monday night (May 5). Under ideal conditions (a dark, moonless sky) up to 60 of these very swift meteors might be seen per hour. The shower appears at about one-quarter peak strength for several days before and after May 6.

If bad weather or bright city lights spoil your view, you can watch webcasts of Eta Aquarid meteor shower Monday night, courtesy of NASA and the Slooh community telescope.

This year will be a very good year to watch for them because the moon will be one day from First Quarter phase which means it will have long since set when the stars of the constellation Aquarius make their appearance in the southeast sky during the early morning hours and will provide absolutely no interference to viewing these swift streaks of light.

There is, however, a bit of a catch.

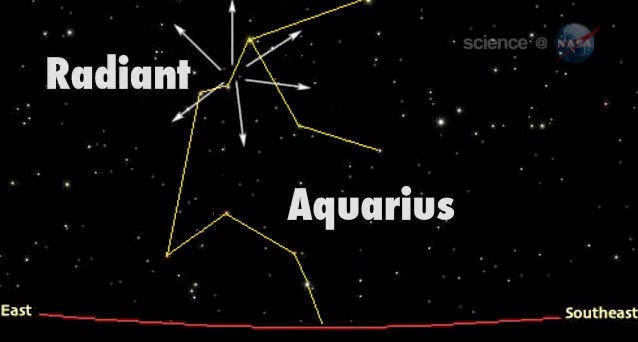

This sky map from NASA depicts the origin the Eta Aquarid meteor shower in the constellation Aquarius in the night sky. The Eta Aquarids are left over material from Halley's Comet.Pin It This sky map from NASA depicts the origin the Eta Aquarid meteor shower in the constellation Aquarius in the night sky. The Eta Aquarids are left over material from Halley's Comet.

Credit: NASA

What’s the point?From places south of the equator, the Eta Aquarids put on very good show; Australians consider them to be the best meteor display of the year. But for those watching from north of the equator, it’s a much different story.

The radiant (the origin point of these meteors) is within the "Water Jar" of the constellation Aquarius, which begins to rise above the eastern horizon around 3 a.m. your local time, but unfortunately, never really gets very high as seen from north temperate latitudes. And soon after 4 a.m., morning twilight will begin to brighten the sky.

So if you're hoping to see up to 60 meteors per hour, forget it. With the radiant so low above the horizon, the majority of those meteors will be streaking below the horizon and out of your view. In fact, from North America, typical Aquarid rates are only 10 meteors per hour at 26 degrees north latitude (for Miami, Florida, or Brownsville, Texas); five meteors per hour at 35 degrees latitude (Los Angeles, California or Cape Hatteras, N.C.); and practically zero to the north of 40 degrees latitude (New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia).

"So," you might ask, "What's the point of getting up before dawn to watch?"

The answer: You might still see something spectacular.

Astrophotographer Justin Ng of Singapore sent in a photo of an Eta Aquarid meteor taken at Mount Bromo, East Java, Indonesia, May 5, 2013.

Credit: Justin Ng

Catch an earthgrazer

For most, perhaps the best hope is perhaps catching a glimpse of a meteor emerging from the radiant that will skim the atmosphere horizontally — much like a bug skimming the side window of an automobile.

Meteor shower watchers call such shooting stars "earthgrazers." They leave colorful, long-lasting trails. "These meteors are extremely long," says Robert Lunsford, of the International Meteor Organization. "They tend to hug the horizon rather than shooting overhead where most cameras are aimed."

"Earthgrazers are rarely numerous," cautions Bill Cooke, a member of the Space Environmentsteam at the Marshall Space Flight Center. "But even if you only see a few, you're likely to remember them."

If you do catch sight of one early these next few mornings, keep in mind that you'll likely be seeing the incandescent streak produced by material which originated from the nucleus of Halley's Comet. When these tiny bits of comet collide with Earth, friction with our atmosphere raises them to white heat and produces the effect popularly referred to as "shooting stars."

So it is that the shooting stars that we have come to call the Eta Aquarids are really an encounter with the traces of a famous visitor from the depths of space and from the dawn of creation.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing picture of an Eta Aquarid meteor, or any other night sky view, that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

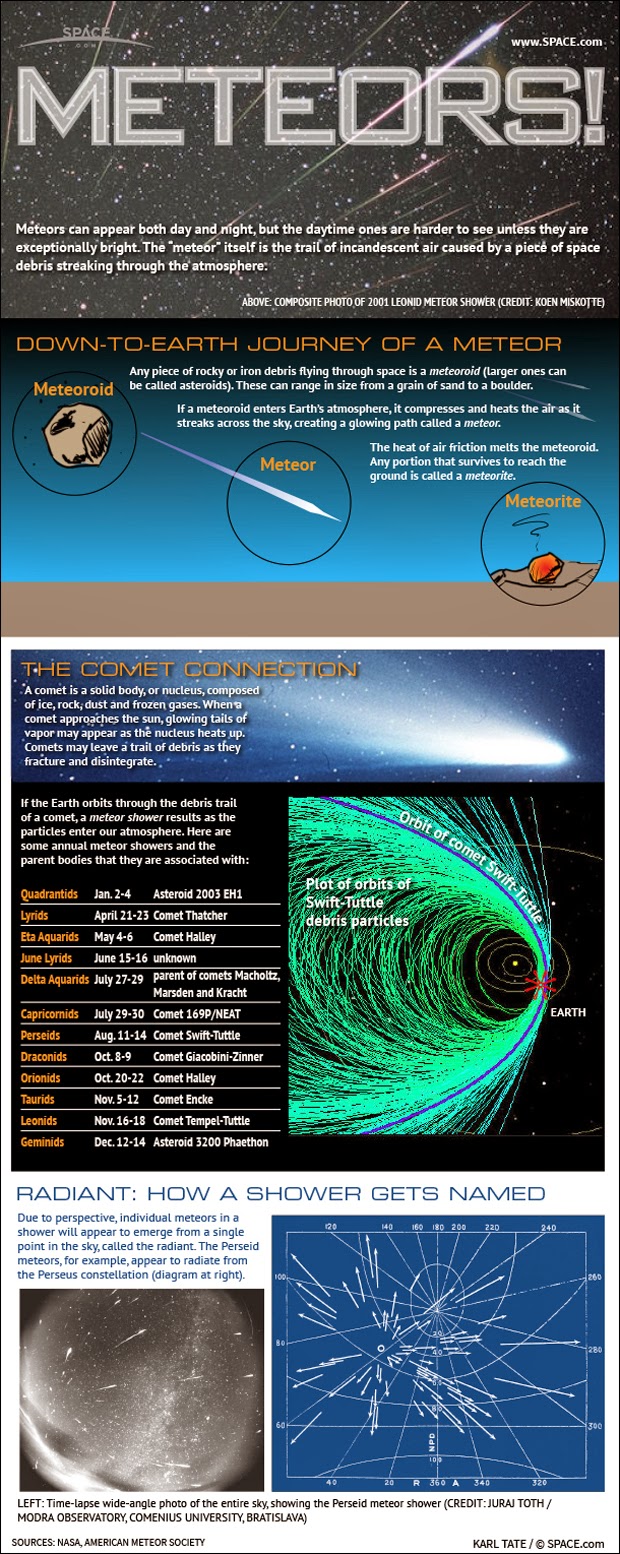

Learn why famous meteor showers like the Perseids and Leonids occur every year.Learn why famous meteor showers like the Perseids and Leonids occur every year.

Credit: Karl Tate space.com