At Burger King

A few hours ago, I drove for dinner to this Burger King (had a small fries, and a single stacker.) This place is the polar opposite of the Buttermilk Sauce Jack In the Box. Whilst I was waiting in line, another gentleman showed up behind me. He admired the cow I always wear on the straps of my hadbag (it sits atop my shoulder and makes the straps more comfortable...it's really supposed to go on a seatbelt for kids, but, it serves very nicely in this function.) We, the gentleman and I, started chatting, and he told me that he was going to be 88 on the 29th of this month. I said "No way!" He looked very young to me. He then told me he was a WWII vet, and that he had a horrible time after, suffering 17 strokes, and some other horrific stuff. He was worried his speech was slurred. I assured him it was not, and that he sounded perfect (which he did.) He then told me that he'd just retired only five months ago, and I was just, like, damn! The dude was amazeballs. Wish I'd been able to stay longer and have a proper natter with this extraordinary African American gentleman. Maybe I'll see him again at the Burger King. I can only hope.

By Bonnie L. Cook, Inquirer Staff Writer

POSTED: January 30, 2012

Just before Christmas, Deveta Johnson saw something in the trash in Norristown that looked like an old pile of grocery bags.

She looked closer and found a tattered photo album with hundreds of World War II-era snapshots of African Americans, in wartime Europe and going about their daily lives in rowhouse Philadelphia.

"Wait a minute," mused Johnson, who had listened to her grandfather's countless war stories. "This shouldn't be in the trash."

Her decision to take the album home and show it to her mother, Valoree Nelson, has preserved for posterity what might have been lost to a landfill. In mid-January, Nelson turned the album over to the Historical Society of Montgomery County.

"I walked there in the rain with my grandson," said Nelson, a retiree from Norristown.

Experts on historic collections who have seen the photos called the album a rare find and remarkable portrait of African American life in the mid-20th century.

"African American history has been for so many years neglected," said Jeffrey R. McGranahan, the historical society's collections manager. "You really get the sense that these were real people who went places and had family gatherings."

The snapshots so intrigued McGranahan that he began searching for clues to the identity of the tall man who seems to be the thread that holds the album together.

The man appears in khaki uniform mostly in wartime France, surveying rubble, standing outside cathedrals, and climbing atop downed Nazi airplanes as though they were souvenirs. In one photo taken on VE-Day, he's in Paris with his G.I. buddies near lines of smiling women.

Museum experts believe the man was likely a first sergeant with the 389th Engineer General Service Regiment, Company E. They know that because the man and two G.I.s are posed with a telltale U.S. Army sign.

The 389th Regiment, a racially segregated unit, landed in England in December 1943 and went to France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany before departing from France in August 1945. It was deactivated that November, according to military records.

The 389th began as a battalion. When reformed as a regiment in 1943, it supplied skilled labor to build hospitals, camps, roads, bridges, and railways. It also laid pipelines for water and gasoline.

"The general service regiments had more soldiers and less equipment, the theory being they would be more labor," said Troy Morgan, director of the U.S. Army Engineer Museum at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. "It was not unusual to have a black regiment doing general service."

Another snapshot depicts the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupre, Belgium, with white crosses marking the neat rows of graves. The photographer appears to be singling out the marker for Bernard E. McCabe, who died Nov. 30, 1944.

McCabe, a private first class in the 289th Infantry Regiment, 75th Division, was from Pennsylvania.

On the home front, the tall man, heavier with age, appears doing yard work outside rowhouses with bay windows in Philadelphia. There are photos of the playing field on Hunting Park Avenue, the intersection of Broad and Carlisle Streets, and a pharmacy at 1540 Butler St.

There are also photos of a woman in a black cap and gown. The woman poses in front of a license in a pharmacy where children sit on stools at a soda fountain. She appears again wearing a dramatic hat and fur coat.

What's missing from the album, though, are names and dates to tie the images together. And the story of how the album ended up in the trash on the 800 block of Cherry Street in Norristown.

"Who would put the book together and not put any names?" Nelson asked. "Who would throw away something like that?"

McGranahan thinks someone in a hurry ripped snapshots out of two different albums and threw them onto the pages of the makeshift book, made out of brown paper bags from Fiore's Supermarket.

The grocery chain once had a presence in Norristown but closed its stores in the 1980s.

McGranahan seeks the public's help in finding the tall man's relatives so the album can be returned to them. Barring that, he hopes to place it in a suitable museum.

"If there are no members of the family left, it would end up in a geographical repository that would be appropriate. Or, if it stays here, that would be good, too," he said.

Photo album rescued from trash a trove of WWII African American life

POSTED: January 30, 2012

Just before Christmas, Deveta Johnson saw something in the trash in Norristown that looked like an old pile of grocery bags.

She looked closer and found a tattered photo album with hundreds of World War II-era snapshots of African Americans, in wartime Europe and going about their daily lives in rowhouse Philadelphia.

"Wait a minute," mused Johnson, who had listened to her grandfather's countless war stories. "This shouldn't be in the trash."

Her decision to take the album home and show it to her mother, Valoree Nelson, has preserved for posterity what might have been lost to a landfill. In mid-January, Nelson turned the album over to the Historical Society of Montgomery County.

"I walked there in the rain with my grandson," said Nelson, a retiree from Norristown.

Experts on historic collections who have seen the photos called the album a rare find and remarkable portrait of African American life in the mid-20th century.

"African American history has been for so many years neglected," said Jeffrey R. McGranahan, the historical society's collections manager. "You really get the sense that these were real people who went places and had family gatherings."

The snapshots so intrigued McGranahan that he began searching for clues to the identity of the tall man who seems to be the thread that holds the album together.

The man appears in khaki uniform mostly in wartime France, surveying rubble, standing outside cathedrals, and climbing atop downed Nazi airplanes as though they were souvenirs. In one photo taken on VE-Day, he's in Paris with his G.I. buddies near lines of smiling women.

Museum experts believe the man was likely a first sergeant with the 389th Engineer General Service Regiment, Company E. They know that because the man and two G.I.s are posed with a telltale U.S. Army sign.

The 389th Regiment, a racially segregated unit, landed in England in December 1943 and went to France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany before departing from France in August 1945. It was deactivated that November, according to military records.

The 389th began as a battalion. When reformed as a regiment in 1943, it supplied skilled labor to build hospitals, camps, roads, bridges, and railways. It also laid pipelines for water and gasoline.

"The general service regiments had more soldiers and less equipment, the theory being they would be more labor," said Troy Morgan, director of the U.S. Army Engineer Museum at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. "It was not unusual to have a black regiment doing general service."

Another snapshot depicts the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupre, Belgium, with white crosses marking the neat rows of graves. The photographer appears to be singling out the marker for Bernard E. McCabe, who died Nov. 30, 1944.

McCabe, a private first class in the 289th Infantry Regiment, 75th Division, was from Pennsylvania.

On the home front, the tall man, heavier with age, appears doing yard work outside rowhouses with bay windows in Philadelphia. There are photos of the playing field on Hunting Park Avenue, the intersection of Broad and Carlisle Streets, and a pharmacy at 1540 Butler St.

There are also photos of a woman in a black cap and gown. The woman poses in front of a license in a pharmacy where children sit on stools at a soda fountain. She appears again wearing a dramatic hat and fur coat.

What's missing from the album, though, are names and dates to tie the images together. And the story of how the album ended up in the trash on the 800 block of Cherry Street in Norristown.

"Who would put the book together and not put any names?" Nelson asked. "Who would throw away something like that?"

McGranahan thinks someone in a hurry ripped snapshots out of two different albums and threw them onto the pages of the makeshift book, made out of brown paper bags from Fiore's Supermarket.

The grocery chain once had a presence in Norristown but closed its stores in the 1980s.

McGranahan seeks the public's help in finding the tall man's relatives so the album can be returned to them. Barring that, he hopes to place it in a suitable museum.

"If there are no members of the family left, it would end up in a geographical repository that would be appropriate. Or, if it stays here, that would be good, too," he said.

How Firefighters Cope With Profound Tragedy

by ALAN GREENBLATT

July 01, 2013 5:55 PM

http://www.npr.org/2013/07/01/197721479/how-firefighters-cope-with-profound-tragedy?ft=1&f=1001

July 01, 2013 5:55 PM

http://www.npr.org/2013/07/01/197721479/how-firefighters-cope-with-profound-tragedy?ft=1&f=1001

It's not that firefighters are never afraid, but they have too many other things to worry about to give in to fear.

Especially the elite wildland crews known as hotshots.

"Fear is not an aspect of the job, per se," says David Simpson, superintendent of the hotshot crew based in Santa Fe, N.M. "It's the day-to-day tasks you perform time and time again that concern us more than the fire changing directions."

There are about 100 hotshot crews in the U.S. Working in teams of 20, they are the ones who hack out a fire line in hopes of containing a raging brush fire.

The 19 firefighters who died in Arizona on Sunday were part of a Prescott fire department hotshot team, but many other hotshots work for the U.S. Forest Service.

"The fire service as a whole understands that there is a definite risk relative to the work that we perform to protect our communities," says Ron Siarnicki, executive director of the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation. "Any time you engage in fire, there is a chance you can perish."

The risk of death for firefighters has actually been decreasing in recent years. There's been greater attention paid to the other occupational hazards they face — far more are killed by heart attack and vehicular accidents than fire itself.

Last year, 73 firefighters died in the line of duty, according to the foundation, down from an annual average of about 100.

But it's early in what's already been an active season. Four fires alone — in Prescott and in West, Bryan and Houston, Texas — have caused 35 deaths combined, close to half of last year's total.

Fire departments are experimenting with new methods to help their men and women cope with grief and the high level of stress associated with the job.

"They pay us hazard pay for a reason," Simpson says. "There is an inherent risk in wild-land firefighting."

Not Yet Time To Grieve

Hotshot squads work together, day and night, throughout the Western fire season. Typically, they work for 14 days straight out in the field, before heading back to the towns where they're based for two days of mandatory rest.

The highly trained hotshots will typically each work more than 1,000 hours of overtime in a single season.

"That's the toughest part of the job, not always being able to take a shower, not being able to talk to family and friends," says Simpson, the Santa Fe superintendent. "It grinds on you during a long season."

Simpson's crew is currently active, working to contain the Silver City fire in northern Nevada. After they get their break, he says, he'll see which ones need to talk through the deaths of their fallen comrades in Arizona.

Even in Arizona, firefighters remain too busy to grieve.

"Right now, they need to bury their dead, they need to continue fighting the fire," says Ralph Esposito, a retired firefighter in New York City.

Counseling One Another

Esposito says he knew 109 firefighters who died on Sept. 11, 2001. Since then, he's counseled hundreds if not thousands of firefighters who have suffered loss.

"You know what you felt when you went through it and you share that experience," he says. "You just give them a heads up, what's coming down the pike at them."

That shared experience can be invaluable, and familiar.

No one fights a fire alone. Whatever firefighters do, they do it as a team.

Some departments are seeking to turn that sense of camaraderie into an institutionalized source of support. The fallen firefighters association is offering training for peer counseling programs, based on models developed in the armed services.

A lot of it is simple stuff, like checking back with a peer who seems troubled, rather than just shrugging some behaviors off.

"The idea is that if you get into a mode of stress first aid every day, then when you have the catastrophic occurrence, it's second nature to the organization," Siarnicki says.

Not In It Alone

Teams of both counselors and fire survivors will be descending on Arizona in the coming days. It may take some time, maybe three or four weeks, for firefighters to be ready to talk about their loss, Esposito says.

Our society expects first responders to be heroic, which can make it even more difficult for them to express their emotions and admit to vulnerability.

An event of such magnitude as the Yarnell Hill fire near Prescott can offer an opportunity for firefighters to talk more generally about their fears, says Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine who has consulted with fire departments.

"It gives people a way to begin talking not only about that loss, but the other job stressors," she says. "The important thing to understand is that very few people are completely impervious to the effects of trauma, and you don't want them to be."

Still, there's a tension inherent in departments relying on peers to keep an eye on their buddies. They can't offer the same level of confidentiality that professional counselors can.

"Firefighters may feel they have to be careful, because if they disclose too much about how they're feeling, it becomes a question about fitness for duty," Yehuda says.

Scarred But Surviving

Firefighters tend not to "sit around the kitchen table at the fire station, talking about how there's a good chance we're going to die today," Siarnicki says.

Still, people who fight fires recognize that there have been preventable deaths in the past, and they're interested in making sure that they don't happen again.

They're also interested in coping with the sort of loss that seems endemic to the profession.

Most firefighters will have their nightmares, yet can come through a horrific experience scarred but OK, says Esposito. A smaller number will need professional help, while a few may require drugs to help regain their balance.

"There's no right or wrong way to grieve," he says.

But firefighters understand the risks that are involved with their job, he adds.

"Sometimes, no matter how right you are, people are going to die," Esposito says. "You don't work for IBM. You didn't sign up for that."

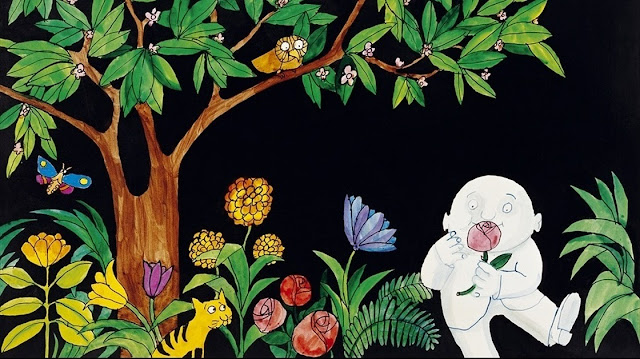

Tomi Ungerer

Children's-book writer Maurice Sendak learned a lot from author and artist Tomi Ungerer. In Far Out Isn't Far Enough, a new documentary about Ungerer, Sendak says, "I learned to be braver than I was. I think that's why [Where The Wild Things Are] was partly Tomi — his energy, his spirit. I'm proud of the fact that we helped change the scene in America so that children were dealt with like the intelligent little animals we know they are."

With a champion in their shared editor, Ursula Nordstrom, Sendak and Ungerer broke the rules of American children's literature in the 1950s and '60s. They created stories and illustrations that many adults found too frightening and rebellious for children — but that kids themselves loved. Ungerer's series of books about the Mellops, a family of adventurous and resourceful pigs who often found themselves in scary situations, was particularly popular.

Ungerer didn't mind scaring kids, because he believed in their ability to cope with and adapt to life's difficulties. He himself had witnessed terrifying things as a child growing up on the French-German border, in Alsace, during World War II. His work, he says, reflects his experience.

"Most of my children's books have fear elements," he tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross. "But I must say, too, to balance this fact, that the children in my books are never scared. ... I think fear is an element which is instilled by the adults a lot of time. I remember even in the bombings and whatever, we were always joking away."

Many Americans have never heard of Ungerer because, in the early 1970s, his books were virtually banished in the United States after he started doing erotic illustrations for books targeted at adults. Ungerer soon returned to Europe, where he lives today. He says Europeans are much more accepting of the fact that his work can plumb the imaginations of both children and adults.

"In Europe," he says, "I have absolutely no problem. I did an erotic book which is based on the Kama Sutra, but instead of human beings, the positions are taken up by frogs. People come up to me and say, 'I was brought up with you. I was 13 years old, and I saved money to buy your Kama Sutra.' "

On Fear vs. Anxiety:

"To be scared is one thing; anxiety is another one. ... If you are in a battle and you have bombs and bullets and shrapnel and everything is going up in the air, that's why you can be scared. But it doesn't really compare to the anxiety. You see, the anxiety ... is something much deeper in a way, because it sticks to you all the time. Are we going to make another day? Are we going to be arrested? ... It's all the impending menace, you know, all the time, all the time. And that's anxiety. I find anxiety worse than fear."

On growing up in Hitler's Germany:

"I remember I had to do a portrait of the Fuhrer, you know, giving a speech, and put a stein of beer on this thing. Well, the Fuhrer didn't drink, but still, you know, nobody ever objected. The thing is, no matter what tyranny, you can always get away, maybe not with murder, but with a few other things. And your mind is always free. Nobody can take away your mind.

"We were brought up to become soldiers. ... [T]hey would say, 'Don't think. The Fuhrer thinks for you.' But then it was reassuring, too, because I was not a good pupil, and then the teachers would say to me ... 'Don't worry, the Fuhrer needs artists and all that.' I mean, the whole thing was geared to win over the children away from their parents."

On his early career in New York:

"It was a land of opportunity. It was really incredible how everybody was so nice. In those days you could call any art director or editor just like this, and the secretary would give you an appointment and you could come there and show your work. I remember I arrived with $60 in my pocket, so I didn't have a portfolio, and I was carrying just my drawings, you know, under my arms.

Maurice Sendak: On Life, Death And Children's Lit

Author Interviews

Lemony Snicket Dons A Trenchcoat:

"And one day it started raining, and I went into a pharmacy — it was on 43rd Street and Broadway, and I think it's still there. And I asked for a box, you see, for my drawings. So they gave me a box that created quite a sensation. because it was a wholesale box for condoms.

"[I]t was incredible how quickly I was able to settle down and work. And I would say I was enough of [a] success to be able to buy a house in New York three or four years later. ... And I'm very grateful for that, really. New York — there's no city in my life I've ever loved as much as New York."

On his mother's affection:

"My answer for [Maurice Sendak and Else Holmelund Minarik's] A Kiss for Little Bear was No Kiss for Mother, because ... my mother loved me much too much, and she poured her affection in the most sloppy ways — I mean over my cheeks and everywhere. And I couldn't stand to be kissed or even touched by my mother. She really overdid it."

On being forced to learn German:

"The Nazis arrived, and after three months it was forbidden to speak a word of French. You could be arrested for a bonjour or just a merci. Just any word in French, you could be immediately arrested. I had to learn German in three months — which shows you that with a knife on your neck, you can learn a language in three months."

Warp Drives

Why Warp Drives Aren't Just Science Fiction

Jillian ScharrDate: 26 June 2013 Time: 10:31 AM ET

CREDIT: Namco Bandai

Astrophysicist Eric Davis is one of the leaders in the field of faster-than-light (FTL) space travel. But for Davis, humanity's potential to explore the vastness of space at warp speed is not science fiction.

Davis' latest study, "Faster-Than-Light Space Warps, Status and Next Steps" won the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics' (AIAA) 2013 Best Paper Award for Nuclear and Future Flight Propulsion.

TechNewsDaily recently caught up with Davis to discuss his new paper, which appeared in the March/April volume of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society and will form the basis of his upcoming address at Icarus Interstellar's 2013 Starship Congress in August.

"The proof of principle for FTL space warp propulsion was published decades ago," said Davis, referring to a 1994 paper by physicist Miguel Alcubierre. "All conventional advanced propulsion physics technologies are limited to speeds below the speed of light … Using an FTL space warp will drastically reduce the time and distances of interstellar flight."

Warp speed: a primer

Before delving into Davis' study, here's a quick review of faster-than-light space travel:

According to Einstein's theory of special relativity, an object with mass cannot go as fast or faster than the speed of light. However, some scientists believe that a loophole in this theory will someday allow humans to travel light-years in a matter of days.

In current FTL theories, it's not the ship that's moving — space itself moves. It's established that space is flexible; in fact, space has been steadily expanding since the Big Bang.

By distorting the space around the ship instead of accelerating the ship itself, these theoretical warp drives would never break Einstein's special relativity rules. The ship itself is never going faster than light with respect to the space immediately around it.

Davis's paper examines the two principle theories for how to achieve faster-than-light travel: warp drives and wormholes.

The difference between the two is the way in which space is manipulated. With a warp drive, space in front of the vessel is contracted while space behind it is expanded, creating a sort of wave that brings the vessel to its destination.

With a wormhole, the ship (or perhaps an exterior mechanism) would create a tunnel through spacetime, with a targeted entrance and exit. The ship would enter the wormhole at sublight speeds and reappear in a different location many light-years away.

In his paper, Davis describes a wormhole entrance as "a sphere that contained the mirror image of a whole other universe or remote region within our universe, incredibly shrunken and distorted."

Sci-fi fans, for warp drives, think "Star Trek" and "Futurama." For wormholes, think "Stargate."

Mirror, mirror on the hull

The next question is: how to create these spacetime distortions that will allow vessels to travel faster than light? It's believed — and certain preliminary experiments seem to confirm — that producing targeted amounts of what's called "negative energy" would achieve the desired effect.

Negative energy has been produced in a lab via what's called the Casimir effect. This phenomenon revolves around the idea that vacuum, contrary to its portrayal in classical physics, isn't empty. According to quantum theory, vacuum is full of electromagnetic fluctuations. Distorting these fluctuations can create negative energy.

According to Davis, one of the most promising methods for creating negative energy is called the Ford-Svaiter mirror. This is a theoretical device that would focus all the quantum vacuum fluctuations onto the mirror's focal line.

"When those fluctuations are confined there, they have a negative energy," said Davis. "You could have types of negative energy that could make a wormhole that you could put a person through and, if you make a bigger mirror, put a starship through. The [mirror] is scalable … that's the beauty of it."

Davis described a theoretical configuration of Ford-Svaiter mirrors that could enable FTL spaceflight: "For a traversable wormhole, it'll have to be separate Ford-Svaiter mirrors [arranged] in an array to create the wormhole and then a ship with mirrors attached to it to extend the wormhole to the destination star."

The concern there is how to target the wormhole's exit.

"We don't know the answer to that question yet," said Davis. "Einstein's theory of general relativity doesn't answer it."

That's the difference between the fields of physics and engineering, Davis explained. According to our current understanding of physics, targeting the wormhole's exit is possible, but engineers have yet to figure out how to achieve it. [See also: NASA Turns to 3D Printing for Self-Building Spacecraft]

"On screen, Number One."

Another issue addressed in Davis' paper is how to navigate an FTL starship.

"If you're in a wormhole, you don't go faster than light — you're going at normal speeds, but your visualization and stellar navigations are all gone [because] … there are no stars to navigate by."

The iconic image of stars streaking by a spaceship viewscreen popularized by franchises like "Star Trek" and "Star Wars" simply isn't accurate, said Davis. "The light that goes through the wormhole gets distorted … you're going to have a very weird visual display."

This is because the negative energy necessary to create a wormhole or warp drive creates a repulsive gravity that distorts light around the ship.

So ships moving at faster-than-light speeds will not be able to observe their surroundings to calculate their location. Astronauts will have to rely on sophisticated computer programs to calculate their probable location. "You'll need something on the order of a supercomputer equipped with parallel processing," said Davis. "[The computer is] going to have to do all the figuring out … [using] input data from the last position and estimating."

This is more of a concern with warp drives, which are actively reshaping space as they travel, but not as much with traversable wormholes, whose entrances and exits will probably be preset before flight. "You can only go one way through the wormhole, so it's not like you're going to get lost," said Davis

It's also important for the computer to be able to produce some kind of visual representation of its flight plan and spatial location. These images would then be rendered and displayed in the starship's cockpit or bridge for the crew to see and study. "It'll help the human psychological need for understanding, in real time, what the position changes of the stars are going to look like," said Davis.

Where no one has gone before

At the heart of Davis' paper is the principle — supported by rigorous scientific theory — that faster-than-light travel is a real and even tangible possibility. The last section of the paper proposes nine "next steps" that would push the field toward engineering prototypes and other practical tests of faster-than-light theories.

These steps include creating computer simulations to model the structure and effects of space warps. Davis also calls for more rigorous exploration of the Ford-Svaiter mirror, which is still a largely theoretical device. The mirror is just one possible way to generate negative energy; further study is needed to determine whether there are any other practical methods of achieving the same effect. [See also: Hypersonic 'SpaceLiner' Aims to Fly Passengers in 2050]

Davis describes the development and implementation of space-warp travel as "technically daunting" in his paper, but in conversation, he said he has no doubt that faster-than-light travel will someday be not only possible, but necessary.

"The Earth is subjected to natural and outer space and ecological disasters, so life is too fragile, while the planets in the solar system are not very hospitable to human life. So we need to explore extrasolar planets for alternative homes," Davis said.

"This is all part of the growth and evolution of the human race."

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Email jscharr@technewsdaily.com or follow her @JillScharr. Follow us @TechNewsDaily, on Facebook or on Google+. Originally published on TechNewsDaily.