Mission Control

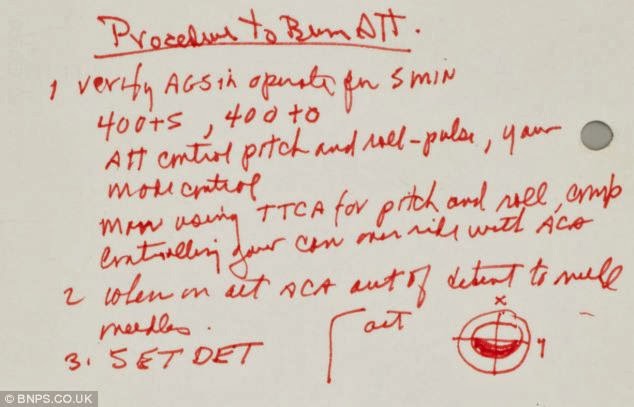

The following notes were made and used by Jim Lovell to work out how to perform a vital 'burn':

Mission Control:

The original crew of Apollo 13 were Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly and Fred Haise (pictured left to right). Mattingly missed the mission due to illness

A celebration erupts at Mission Control after a successful splashdown of the Apollo 13 Odyssey

on April 17, 1970.

Credit: NASA.

In this historical photo from the U.S. space agency, three of the four Apollo 13 Flight Directors applaud the successful splashdown of the Command Module "Odyssey" while Dr. Robert R. Gilruth, Director, Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), and Dr. Christopher C. Kraft Jr., MSC Deputy Director, light up cigars (upper left). The Flight Directors are from left to right: Gerald D. Griffin, Eugene F. Kranz and Glynn S. Lunney.

Apollo 13 crew members, astronauts James A. Lovell Jr., Commander; John L. Swigert Jr., Command Module pilot, and Fred W. Haise Jr., Lunar Module pilot, splashed down on Apr. 17, 1970, at 12:07:44 (CST) in the South Pacific Ocean, approximately four miles from the Apollo 13 prime recovery ship, the U.S.S. Iwo Jima.

Swann's Way

More to Remember Than Just the Madeleine

Celebrating the Centennial of Proust’s ‘Swann’s Way’

By JENNIFER SCHUESSLER

Published: November 7, 2013

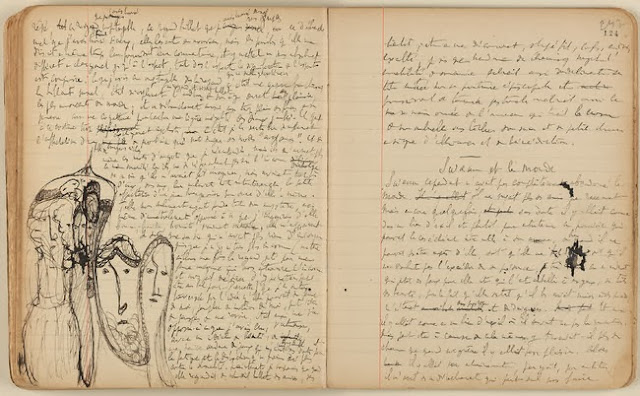

Marcel Proust's notes and doodles for "Swann's Way," published in 1913.

Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF), Paris, France, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

But in recent days, the radio host Ira Glass, the pastry chef Dominique Ansel and a crew of other long haulers have been worrying less about leg cramps than semicolons.

The marathon in question is a weeklong “nomadic reading” of Marcel Proust’s “Swann’s Way” that will celebrate the centennial of that first installment of “In Search of Lost Time” by bringing Proust’s endlessly subdividing sentences, microscopic self-consciousness and, yes, plenty of madeleines to seven Proust-appropriate locations across New York City.

In Mr. Glass’s case, that would be a bed in a room at the Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where, at 7 p.m. on Friday, he will recite the book’s opening — “For a long time, I went to bed early” — from under the covers before passing the baton, so to speak, to the next in a chain of nearly 120 readers recruited by the French Embassy’s cultural services division.

“There’s a corny literalness that I appreciate,” Mr. Glass said by telephone, before admitting that his knowledge of the book, perhaps appropriately, lay more in the realm of Proustian memory than recent experience. “Besides, when the French Embassy asks you to do something, you say yes.”

This year’s centennial has already been honored by academic conferences and an exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum, featuring manuscripts that had never before traveled outside France. But the mostly English-language nomadic reading, to be followed next weekend by a more agoraphobic-friendly 20-hour overnight event at Yale University staged inside a re-creation of Proust’s cork-lined bedroom in Paris, offers a chance for para-Proustologists, as scholars have been known to call their amateur counterparts, to get into the act.

“In France, ordinary people are more likely just to read Proust at home,” said Antonin Baudry, the cultural counselor of the French Embassy and one of the event’s organizers. “This reading is a way of showing how Proust is alive in the United States.”

It also represents a chance for the rarefied Proust, who took a half-step into the mainstream in the late 1990s with books like “The Year of Reading Proust” and “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” to grab some pop-culture market share from the perennial marathon-reading favorite, “Ulysses.”

Sure, Bloomsday has the Guinness. But the nomadic reading will have madeleines baked by Mr. Ansel (better known as the inventor of the Cronut) and a deep bench of partisans eager to plump for the more intimate pleasures of Proust.

“As a young writer, I felt there were two kinds of people: Joyce people and Proust people,” said the novelist Rick Moody, a utility infielder who has also participated in “On the Road,” “Lolita” and “Moby-Dick” marathon readings. “For a long time, I would’ve asserted my allegiance to Joycean qualities. But in my galloping middle age, Proust calls to me more fervently.”

For those lacking the stamina to take in every word of “Swann’s Way” at a gulp, shortcuts are available. Harold Pinter’s unfilmed 1972 “Proust Screenplay,” which boils down all seven volumes of “In Search of Lost Time” to about three hours, will have its first American hearing at a staged reading at the 92nd Street Y in January. If that’s still too long, the classic Monty Python “All-England Summarize Proust Competition” skit is waiting on YouTube.

But for many, the appeal of Proust is precisely that he forces readers to slow down and pay attention. “Proust is a cure for attention deficit,” said Alice Kaplan, the chairwoman of Yale’s French department and an organizer of the reading there. “You just cannot hurry through those sentences.”

Mass readings of “Remembrance of Things Past” (as some partisans of C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation still call Proust’s novel) are not an exclusively American phenomenon. Since 1993, for the project “Proust Lu” (“Proust Read”), the French filmmaker Véronique Aubouy has shot over 100 hours of more than a thousand ordinary people reading the work sentence by sentence, while sitting on top of a tractor, wading in a lake or standing in a hat shop — and she’s only partway through Volume 4.

But in the United States the embrace of the difficult and very French Proust may be a way of asserting one’s allegiance to the madeleine over the freedom fry.

“People here are eager to pull out whatever Proust credentials they have,” said Caroline Weber, a professor of French at Barnard College who is working on a book about three real-life aristocratic women who inspired Proust’s characters. “But in France, Proust doesn’t have that special significance as cultural shorthand. He’s French, and so are they.”

American Proustmania can lead to some awkward cross-cultural moments. Harold Augenbraum, founder of the Proust Society of America and a participant in the nomadic reading, recalled the startled reaction he got a few years ago from the attendant at an Art Nouveau pissoir under Paris’s Place de la Madeleine when he asked if he could lead a tour group of American Proustians in an impromptu reading of a scene in which the moldy smell of another urinal awakens a particularly pungent memory.

“She looked at me like I was out of my mind,” Mr. Augenbraum said. “But that was part of the idea, to make it comic for everyone.”

There may be similarly puzzled reactions at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx on Sunday, should unsuspecting visitors happen upon students from the Lycée Français and the French American School of New York who will be reading (presumably more wholesome) passages in a patch of forest, chosen to represent young Marcel’s paeans to the countryside.

The Yale reading, by contrast, will emphasize Proust’s asthmatic, indoor spirit, though a team of students from Yale’s drama school has been offering coaching sessions to help the 100-plus participants avoid becoming stuck in syntactic dead ends, to say nothing of actual respiratory attacks. “His sentences are completely energetic, and you are completely out of breath reading him,” Ms. Kaplan said. “It’s the asthmatic teaching us breath control.”

Ms. Weber will be reading on Monday at the Oracle Club, a private arts space in Long Island City, Queens, meant to evoke the grand salons Proust frequented before illnesses real and imagined consigned him to bed.

“Maybe I’ll wear a fur coat indoors, and bring my maid and instruct her to run around at various points and open windows,” Ms. Weber said. “Proust would send really funny letters to hostesses saying, ‘I’ll come, but can only come after 11, and only if you open all the windows, then close them when I get there.’ He had all kinds of Mariah Carey-in-the-green-room stipulations. It might be amusing to put on that kind of show.”

Reading Proust: An Introduction

By SAM TANENHAUS

One hundred years after its publication, “Swann’s Way,” the first volume in Marcel Proust’s cycle “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu” — “In Search of Lost Time,” better known to many Anglophone readers as “Remembrance of Things Past,” the Shakespearian title used by Proust’s first English translator — doubles as thematic “overture” and Michelin guide to the most captivating, ambitious and elusive of modern novels.

The glittering surface of “Swann's Way” presents a Manet-like canvas of belle époque France, a sumptuous world of fashionable salons and tranquil summer homes populated by characters — old and young, rich and poor, artists and aristocrats, footmen and physicians — who spring at us with comic ferocity: their sufferings and delusions, their petty cruelties, their self-destructive obsessions and corrosive vanities. By the end of the giant cycle (some 4,000 pages) these fictitious beings will seem realer than the members of one’s own family.

But within the space of far fewer pages, 200 or so, the reader grasps, just as readers did in 1913, that Proust is a novelist of limitless talent: a preternatural observer, inspired mimic, prodigious wit, fluent narrator, ingenious coiner of images and words. And he knows everything, sounding at times like a botanist, at others like a painter, architectural historian, musicologist, literary theorist. He seems to have read every book, seen every play, and absorbed the contents of entire museums along with the principles of medicine, diplomacy, etymology and more.

Yet all this only touches the outskirts of Proust’s herculean purpose. As the sinuous sentences unfold, aphorism following insight, metaphor converted into syllogism, we realize Proust is as rigorous a thinker as he is fabulist, heir to Descartes, companion to Freud. He is not “simply” writing a novel. He is bending the girders of an inherited form into a new science of understanding. He means to unlock the “laws” of human psychology — of hidden motive, desire and crippling habit — and so perhaps arrest, if not defeat, the ravages of “Time.”

We know this is his intent because he frankly tells us so. The novel’s narrator addresses us with the brazen directness of our own moment’s memoirists, though Proust is strangely self-effacing, even his terrifying omniscience grounded in his repeated insistence that he really knows nothing at all.

Inevitably, the first pages of “Swann’s Way” announce that the grand investigation to come must be autobiographical and must begin in childhood, for the impressions gleaned then will determine a lifetime of tiny misconstruals and fatal miscalculations, of revelations that would not surprise us, and they do each time, if only Proust, and we, had been paying closer attention.

These first pages also set forth Proust’s theory of “involuntary memory,” encapsulated in the famous incident of the madeleine soaked in tea. When the narrator presses the spoon to his lips, the sensation looses a tactile flood that transports him to the past — not the known but the latent or repressed past, hitherto concealed from him by the organized recollections of “voluntary” or conscious memory, the prison of falsehood each of us constructs in the effort, we think, to uncover the truth, though in fact it only makes it more elusive. Not that “involuntary memory,” the morsel of tasted cake, makes Proust the master of reality. On the contrary, he is allotted only flickering glimpses, which will accost him unpredictably and, often, woundingly.

“Swann’s Way” and the six novels that follow can be read as the mounting sequence of these glimpses. Everything else, in the rich and varied universe Proust has invented, exists only as the stage for these scattered lightning-flashes. The most cerebral of writers, Proust seeks finally to free himself, and us, from the shackles of intellect and reason.

NOMADIC READING Friday to Thursday; various locations in New York; frenchculture.org.

THE YALE PROUST MARATHON Nov. 16 to 17; New Haven; proustatyale.com.

ON PROUST Panel with William C. Carter, Jennifer Egan, Laurent Mauvignier and Olivier Rolin; Nov. 17, 11 a.m.; 92nd Street Y, 1395 Lexington Avenue; 92y.org.

REWRITING PROUST Panel with authors. Nov. 19, 7 p.m.; Center for Fiction, 17 East 47th Street, Manhattan; centerforfiction.org.

PINTER/PROUST Jan. 16; 92nd Street Y; 92y.org.

Bob Fosse

Biography Of Director Bob Fosse Razzles, Dazzles And Delights

by BOB MONDELLO

November 07, 2013 3:57 PM

On Sept. 23, 1987, opening night of a Sweet Charity revival in Washington, D.C., Bob Fosse and his ex-wife and collaborator Gwen Verdon gave the cast a final pep talk, then left the National Theater to get a bite to eat. They turned right, and about a block away, unknown to the gathering audience, or the cast, Fosse collapsed on the sidewalk. Newspapers the next morning said he died at 7:23 p.m.

I was inside that theater. I later calculated what was happening at 7:23. It was a quintessential Fosse moment: a stagewide bar rising from the floor, a line of dance hall hostesses draping themselves over it, bait for big spenders. Here you can listen to him stage the movie version a few years later.

I had seen a lot of Fosse shows by that time — Damn Yankees, Pippin, Dancin', Chicago — and I had read enough about him to know what was autobiographical in his movie All That Jazz.

So I cracked open Sam Wasson's 700-page biography figuring I knew the score. Hell, knew the score and the steps: those artfully slumped shoulders, knocked knees and pigeon-toes. The bowler hats and black vests worn without shirts, like the one Liza Minnelli sported in the number that introduced her in Cabaret on-screen, leading a chorus that knelt and stomped and sprawled, and used hard-backed chairs for everything but sitting.

But I didn't know the details Wasson gets at about how Fosse taught choreography that often made dancers seem all elbows and knees. First to Verdon, who was his muse before she was his wife, and then, with her help, to the dancers in all his shows.

In one dance the chorus girls all had to extend a foot while leaning back and shooting their arms down at their sides. Fosse gave them an image to help them see exactly how he wanted it: "Ladies," he said, "it's like a man is holding out a fur coat for you and you have to drop your arms in."

"Other directors," writes Wasson, "might give their dancers images for every scene. Bob ... had one for just about every step. These were the lines the dancers' bodies had to speak."

That, I submit, is lovely writing, as is his description of Cabaret as a film "about the bejeweling of horror [that] coruscated with Fosse's private sequins." You can lift samples just like those from virtually every page of this book.

You'll also learn how the director's dark stage imagery mirrored his own life — the wife and girlfriends he cheated on, the down-and-dirty burlesque houses he grew up in, the amphetamines that kept him going, and the barbiturates that calmed him when he lost confidence in his own "razzle-dazzle."

Wasson pictures him as harder on himself than he was on his dancers. In one year, he won a directing triple crown for which no one else had ever even been nominated — An Emmy for Liza With A Z, an Oscar for Cabaret and a Tony for Pippin. And his reaction was utter depression. But out of that depression came Chicago ... a musical vaudeville that looked great at the Tony Awards in 1976.

The revival is about to enter its 14th year on Broadway.

Fosse is filled with the kind of inside detail that comes of substantial research, and vivid descriptions that turn the research into a sort of movie in your head. All the way from little Bobby Fosse's elementary school disappointment when the spotlight faded on him, right through to the moment when Gwen Verdon, the love of his life, cradled Fosse's head on her lap on a D.C. sidewalk, just blocks from an audience he was at that very moment razzle-dazzling to beat the band.

Excerpt: Fosse

Gwen Verdon, legally Mrs. Bob Fosse, was smiling big. She had perched herself in the foyer beside a tray of champagne flutes so that, with the help of a few servers, she could pass them out between air-kisses and the occasional embrace. Verdon held herself with a poise befitting her legacy as the one-time greatest musical-comedy star in the world, and though her glory days were far behind her, one could immediately recognize the naughty, adorable, masterfully flirtatious song-and-dance girl Broadway had fallen in love with. Fosse's best friend, Paddy Chayefsky, had called her the Empress.

Around eight o'clock, the flurry of famous and obscure, some of them in black tie, others dressed merely for a great time, hugged and kissed their way off the pavement and into Tavern on the Green. They passed Verdon as they headed down the mirrored hall to the Tavern's Crystal Ballroom, a fairy-tale vision of molded ceilings and twinkling chandeliers where light was low and sweet and a dark halo of cigarette smoke hovered over the ten-piece band. They played before a wide-open dance floor and dozens of tables apoof with bouquets. Each place was set with a miniature black derby, a tiny magic wand, and a little toy box that, when opened, erupted with cheers and applause.

For Fosse's haute clique of friends, lovers, and those in between, the night of October 30, 1987, was the best worst night in show-business history. In work or in love, they had all fought Fosse (in many cases, they had fought one another for Fosse), and they had always come back. No matter the pain he caused, they understood that on the other side of hurt, grace awaited them. His gift — their talent — awaited them. But now that Fosse was dead — this time permanently — many wondered how his wife, daughter, and armies of girlfriends, separated by their own claims on his love, would learn to hold his legacy.

The site of sundry Fosse movie premieres and opening-night bashes, Tavern on the Green had hosted the oddest pairings of writers, dancers, and production people, old and young, sober and drunk, but tonight, the dance floor seemed to scare them away.

People talked in separate clusters. Liza Minnelli cut a line through the procession, squeezed Verdon's hand, and made her way toward Elia Kazan. Then came Roy Scheider. Without stopping, he nodded at Verdon and eased past Jessica Lange, who was wallflowering by Fosse's psychiatrist, Dr. Clifford Sager, and Alan Heim, editor of Fosse's autobiographical tour de force All That Jazz. "Alan," producer Stuart Ostrow said, "you know, Bob always said you edited his life." There was Cy Coleman; Sanford Meisner; Buddy Hackett; Dianne Wiest; Herb Schlein, the Carnegie Deli maître d' who kept linen napkins set aside for Bobby and Paddy, his favorite customers for twenty years. Where was Fosse's ally and competitor Jerome Robbins? (He was free that night, though he'd RSVP'd no.) Peering into the crowd, Verdon spotted what remained of Fosse's tightest circle of friends — Herb Gardner, E. L. Doctorow, Neil Simon, Steve Tesich, Peter Maas, Pete Hamill — all writers, whom Fosse idolized for mastering the page, the one act he couldn't. They were slumped over like tired dancers and seemed lost without Paddy, Lancelot of Fosse's Round Table. "If there is an afterlife," Gardner said, "Paddy Chayefsky is at this moment saying, 'Hey, Fosse, what took you so long?'"

Before his cardiac bypass, Fosse had added a codicil to his will: "I give and bequest the sum of $25,000 to be distributed to the friends of mine listed ... so that when my friends receive this bequest they will go out and have dinner on me."

Fosse thought the worst thing in the world (after dying) would be dying and having nobody there to celebrate his life, so he divided the twenty-five grand evenly among sixty-six people — it came out to $378.79 each — and then had them donate that money back to the party budget so that they'd feel like investors and be more likely to show up. Bob Fosse — the ace dancer, Oscar and Tony and Emmy Award–winning director and choreographer who burned to ash the pink heart of Broadway, revolutionized the movie musical twice, and changed how it danced — died hoping it would be standing room only at his party, and it was. Many more than his intended sixty-six shouldered in — some thought over two hundred came that night — but after a lifetime in show business, having amassed a militia of devoted associates, he had not been sure they all really really loved him. Had he been there, Fosse would have been studying their faces from across the room, keeping track of who told the truth and who told the best lies. Who really missed him? Who pretended to? Who was acting pretentious? Who was auditioning? He would have called Hamill and asked him later that night, waking him up, probably, at two in the morning. Fosse would fondly and faithfully deride the bereaved, but underneath he'd be worrying about the house, how many came, where they laughed, and if they looked genuinely sad.

"This is incredibly sad," said Arlene Donovan on one side of the room.

"I'm having the best time," said Alan Ladd Jr. on another.

Roy Scheider, who had played a version of Fosse in All That Jazz, scrutinized every detail of the party scene from behind his cigarette and said, "It was as if he was orchestrating it." He laughed.

Stanley Donen eyed Scheider. "My God," Donen thought, "I'm watching this with Fosse's ghost."

By midnight many had said their goodbyes, but you wouldn't know it to hear the band, grooving hard on their second wind. Ties were loosened. High heels dangled from fingers. Only the inner circle remained. Here was Fosse's daughter, Nicole. Here was Gwen Verdon, his wife. Here was Ann Reinking, Fosse's girlfriend of many years. Along with his work, they were the living record of his fervor, adored and sinned against, difficult to negotiate, impossible to rationalize.

In a quiet room away from the clamor, Fosse's last girlfriend, Phoebe Ungerer, wept. Then she left.

Suddenly Ben Vereen flew to the dance floor. He threw his hands into the air and then onto his hips and started slithering. At first he was alone, but moments later the crowd caught on. Reinking followed with Nicole and the eternal redhead, Nicole's mother, the Empress. The bandleader upped the tempo to a funk sound with the kind of heavy percussion Fosse loved, and Fosse's three women moved closer together. Verdon, sixty-two; Reinking, thirty-eight; and Nicole, twenty-four — wife, mistress, daughter — started swaying, their arms entwined, moving together in an unmistakably sensual, sexy way. Their eyes closed and their bodies merged with the beat, pulsing together, like a hot human heart. Others joined them. First ex-girlfriends, then writers. A circle formed, closing in around the women, then opened, then closed, ceaselessly breaking apart and coming together. Grief and laughter poured out of them in waves.

From Fosse by Sam Wasson. Copyright 2013 by Sam Wasson. Excerpted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Excerpt: Fosse

The End

Gwen Verdon, legally Mrs. Bob Fosse, was smiling big. She had perched herself in the foyer beside a tray of champagne flutes so that, with the help of a few servers, she could pass them out between air-kisses and the occasional embrace. Verdon held herself with a poise befitting her legacy as the one-time greatest musical-comedy star in the world, and though her glory days were far behind her, one could immediately recognize the naughty, adorable, masterfully flirtatious song-and-dance girl Broadway had fallen in love with. Fosse's best friend, Paddy Chayefsky, had called her the Empress.

Around eight o'clock, the flurry of famous and obscure, some of them in black tie, others dressed merely for a great time, hugged and kissed their way off the pavement and into Tavern on the Green. They passed Verdon as they headed down the mirrored hall to the Tavern's Crystal Ballroom, a fairy-tale vision of molded ceilings and twinkling chandeliers where light was low and sweet and a dark halo of cigarette smoke hovered over the ten-piece band. They played before a wide-open dance floor and dozens of tables apoof with bouquets. Each place was set with a miniature black derby, a tiny magic wand, and a little toy box that, when opened, erupted with cheers and applause.

For Fosse's haute clique of friends, lovers, and those in between, the night of October 30, 1987, was the best worst night in show-business history. In work or in love, they had all fought Fosse (in many cases, they had fought one another for Fosse), and they had always come back. No matter the pain he caused, they understood that on the other side of hurt, grace awaited them. His gift — their talent — awaited them. But now that Fosse was dead — this time permanently — many wondered how his wife, daughter, and armies of girlfriends, separated by their own claims on his love, would learn to hold his legacy.

The site of sundry Fosse movie premieres and opening-night bashes, Tavern on the Green had hosted the oddest pairings of writers, dancers, and production people, old and young, sober and drunk, but tonight, the dance floor seemed to scare them away.

People talked in separate clusters. Liza Minnelli cut a line through the procession, squeezed Verdon's hand, and made her way toward Elia Kazan. Then came Roy Scheider. Without stopping, he nodded at Verdon and eased past Jessica Lange, who was wallflowering by Fosse's psychiatrist, Dr. Clifford Sager, and Alan Heim, editor of Fosse's autobiographical tour de force All That Jazz. "Alan," producer Stuart Ostrow said, "you know, Bob always said you edited his life." There was Cy Coleman; Sanford Meisner; Buddy Hackett; Dianne Wiest; Herb Schlein, the Carnegie Deli maître d' who kept linen napkins set aside for Bobby and Paddy, his favorite customers for twenty years. Where was Fosse's ally and competitor Jerome Robbins? (He was free that night, though he'd RSVP'd no.) Peering into the crowd, Verdon spotted what remained of Fosse's tightest circle of friends — Herb Gardner, E. L. Doctorow, Neil Simon, Steve Tesich, Peter Maas, Pete Hamill — all writers, whom Fosse idolized for mastering the page, the one act he couldn't. They were slumped over like tired dancers and seemed lost without Paddy, Lancelot of Fosse's Round Table. "If there is an afterlife," Gardner said, "Paddy Chayefsky is at this moment saying, 'Hey, Fosse, what took you so long?'"

Before his cardiac bypass, Fosse had added a codicil to his will: "I give and bequest the sum of $25,000 to be distributed to the friends of mine listed ... so that when my friends receive this bequest they will go out and have dinner on me."

Fosse thought the worst thing in the world (after dying) would be dying and having nobody there to celebrate his life, so he divided the twenty-five grand evenly among sixty-six people — it came out to $378.79 each — and then had them donate that money back to the party budget so that they'd feel like investors and be more likely to show up. Bob Fosse — the ace dancer, Oscar and Tony and Emmy Award–winning director and choreographer who burned to ash the pink heart of Broadway, revolutionized the movie musical twice, and changed how it danced — died hoping it would be standing room only at his party, and it was. Many more than his intended sixty-six shouldered in — some thought over two hundred came that night — but after a lifetime in show business, having amassed a militia of devoted associates, he had not been sure they all really really loved him. Had he been there, Fosse would have been studying their faces from across the room, keeping track of who told the truth and who told the best lies. Who really missed him? Who pretended to? Who was acting pretentious? Who was auditioning? He would have called Hamill and asked him later that night, waking him up, probably, at two in the morning. Fosse would fondly and faithfully deride the bereaved, but underneath he'd be worrying about the house, how many came, where they laughed, and if they looked genuinely sad.

"This is incredibly sad," said Arlene Donovan on one side of the room.

"I'm having the best time," said Alan Ladd Jr. on another.

Roy Scheider, who had played a version of Fosse in All That Jazz, scrutinized every detail of the party scene from behind his cigarette and said, "It was as if he was orchestrating it." He laughed.

Stanley Donen eyed Scheider. "My God," Donen thought, "I'm watching this with Fosse's ghost."

By midnight many had said their goodbyes, but you wouldn't know it to hear the band, grooving hard on their second wind. Ties were loosened. High heels dangled from fingers. Only the inner circle remained. Here was Fosse's daughter, Nicole. Here was Gwen Verdon, his wife. Here was Ann Reinking, Fosse's girlfriend of many years. Along with his work, they were the living record of his fervor, adored and sinned against, difficult to negotiate, impossible to rationalize.

In a quiet room away from the clamor, Fosse's last girlfriend, Phoebe Ungerer, wept. Then she left.

Suddenly Ben Vereen flew to the dance floor. He threw his hands into the air and then onto his hips and started slithering. At first he was alone, but moments later the crowd caught on. Reinking followed with Nicole and the eternal redhead, Nicole's mother, the Empress. The bandleader upped the tempo to a funk sound with the kind of heavy percussion Fosse loved, and Fosse's three women moved closer together. Verdon, sixty-two; Reinking, thirty-eight; and Nicole, twenty-four — wife, mistress, daughter — started swaying, their arms entwined, moving together in an unmistakably sensual, sexy way. Their eyes closed and their bodies merged with the beat, pulsing together, like a hot human heart. Others joined them. First ex-girlfriends, then writers. A circle formed, closing in around the women, then opened, then closed, ceaselessly breaking apart and coming together. Grief and laughter poured out of them in waves.

From Fosse by Sam Wasson. Copyright 2013 by Sam Wasson. Excerpted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Arc of the Milky Way

Thomas O'Brien sent SPACE.com this image of the Milky Way over Machu Picchu on July 4, 2013. He captured the photo from Putucusi Mountain, which is located across the Urubamba River Valley from the historic sanctuary of Machu Picchu, Peru. Machu Picchu is the dark, saddle-shaped area between mountains on right side of the image where the arc of the Milky Way intersects with the horizon.

Credit: Thomas O'Brien | www.tmophoto.com

The Milky Way, our own galaxy containing the solar system, is a barred spiral galaxy with roughly 400 billion stars. The stars, along with gas and dust, appear like a band of light in the sky from Earth. The galaxy stretches between 100,000 to 120,000 light-years in diameter.