by MICHAELEEN DOUCLEFF

http://www.npr.org/

July 31, 2013 7:05 AM

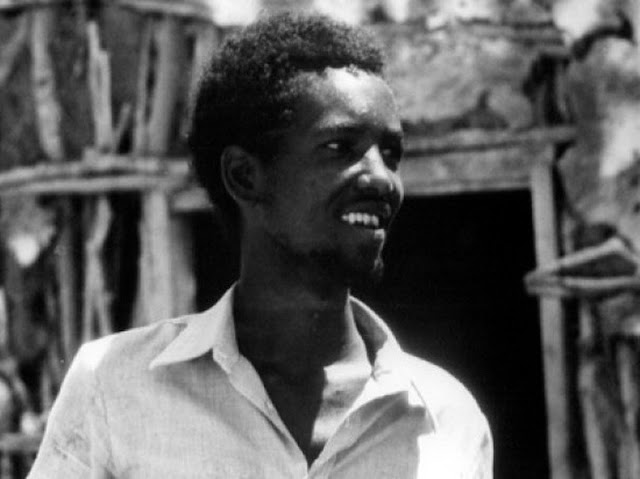

Ali Maow Maalin said he avoided getting the smallpox vaccine as a young man because he was afraid of needles. He didn't want others to make the same mistake with polio.

Photo courtesy of the World Health Organization

One special man in Somalia was at the battlefront of both eradication efforts. He died unexpectedly last week at age 59 of a sudden illness.

Ali Maow Maalin was the last member of the general public to catch smallpox — worldwide. And he spent the past decade working to end polio in Somalia.

World health leaders called Maalin "an inspiration." Even in the weeks before his death, he was leading anti-polio campaigns in some of the most unstable parts of Somalia.

Maalin's fight against polio began in 1977. Jimmy Carter had just been elected U.S. president. Apple Computer had just incorporated in California. And the world was on the verge of wiping out smallpox. Decades of vaccination efforts had pushed the virus into one last corner of the world: Somalia.

Maalin, then a hospital cook near Mogadishu, caught smallpox while driving an infected family to a clinic. He was careful not to spread the disease to anyone. And about three years later, Somalia — and the world — were declared free of smallpox.

A Yemeni child receives a polio vaccine in the capital city of Sanaa. The Yemen government launched an immunization campaign last month in response to the polio outbreak in neighboring Somalia.

After recovering from smallpox, Maalin decided to dedicate his life to eliminating another scourge. "He would always say, 'I'm the last smallpox case in the world. I want to help ensure my country will not be last in stopping polio,'" Dr. Debesay Mulugeta, who leads polio eradication efforts in Somalia, tells Shots.

So in 2004, Maalin officially became a polio vaccinator. He organized volunteers, went door to door immunizing children and helped to convince families the vaccine was safe.

At the time, vaccinating kids in southern Somalia was a dangerous job. Several militia groups were fighting each other, and some vaccinators were even shot at. Many militia leaders thought the vaccine wasn't safe. So Maalin would share his own experience with smallpox, and change their minds.

Maalin told The Boston Globe in 2006 that he had several opportunities to receive the smallpox vaccine, but initially avoided it because he was afraid the shot would hurt. "Now when I meet parents who refuse to give their children the polio vaccine," he told the Globe, "I tell them my story. I tell them how important these [polio] vaccines are. I tell them not to do something foolish like me."

Such tactics helped Maalin and other health workers stamp out Somalia's polio outbreak in 2005. And the country was declared polio-free in 2007.

Last year, there were just 223 cases of polio worldwide. Health leaders hope to have that number down to zero by 2015.

But this spring, polio began to make a comeback in Somalia. A handful of children were paralyzed by the virus in May; since then, Somalia has recorded more than 70 cases.

So Maalin went back to work and started organizing immunization campaigns in one of the most turbulent regions of Somalia. "The area where he worked was not easy because militia controlled access to it," Mulugeta says.

On the second day of the campaign, Maalin got sick. "He had a fever," Mulugeta says. "But he didn't give much attention to it."

A few days later, Maalin was in the hospital and died July 22. "The hospital said it was complicated malaria," Mulugeta tells Shots. "Ali was such a great colleague. I don't think he went for medical service early enough. He was so busy in the field, so focused on monitoring the campaign."