Jürgen Schadeberg’s Chronicles of Apartheid

When German photographer Jürgen Schadeberg left for South Africa, he was 19 years old. Back then he had no idea that he would end up accompanying Nelson Mandela to document apartheid.

"When you're 19 years old, you need an adventure, you have to get out. And I had enough of Germany because of the war." When Jürgen Schadeberg talks about why he left Germany as a teenager, the voice of the 82-year old sounds energetic. Germany was in ruins when his thirst for adventure kicked in. The Second World War destroyed his hometown of Berlin, leaving only poverty, misery and refugees behind.

"I saw in the movies that there was another kind of life," he said. At this point Schadeberg had finished his traineeship in the photo department of the German Press Agency (DPA). With his Leica in hand, he boarded a ship to Cape Town.

Young Schadeberg at age 17 in 1949, a camera always by his side

Schadeberg encountered his first disillusionment on the train from Cape Town to Johannesburg, where he met a man who spoke German. At first he was excited to finally be able to speak his mother tongue after such a long sea voyage. But he soon realized who this fellow passenger was.

"He was an extreme racist and Nazi. His name was Dr. Johannes van Rensburg and he was the head of the Ossewabrandwag," an organization in South Africa that sympathized with the German Nazis and sabotaged the allies' efforts and the South African union against Germany.

This fellow passenger spoke enthusiastically about Hitler and what the apartheid government, which had recently seized power, was going to do. "And I was so shocked that I went to the restaurant car and got drunk. I just couldn't understand it," Schadenberg said with a bitter laugh. In hindsight he said he knows that it was just a taste of what was to come. What he saw in Johannesburg was nothing new to the man who had just left Nazi Germany.

Arrival in South Africa

In 1958 Schadeberg was arrested for protecting his Drum magazine colleague.

The new country depressed and astonished Schadeberg at the same time. In order to make some money as a photographer, he offered his work to Drum magazine, a lifestyle magazine that became the mouthpiece of the oppressed black majority of the population. Schadeberg became head photographer, photo editor and artistic leader. He took pictures of jazz stars such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and Kippie Moeketsi while establishing documentary photography.

"Photography was only news photography: headshots, handshakes, people holding a speech. The pictures were all staged," he said.

With his small Leica, Schadeberg captured daily life situations in smoky jazz bars, at the hairdresser or on the music-filled streets of Johannesburg's Sophiatown district. In the 1950s, while at a photo shoot with movie star and jazz singer Dolly Rathebe for the front page of Drum, Schadeberg learned that working for a "black" magazine could mean trouble for a white photographer.

While photographing jazz star and actress Dolly Rathebe for the cover of Drum magazine, Schadeberg was arrested because 'sex between mixed races' was forbidden.

Schadeberg and Rathebe were arrested at the photo shoot based on a law that forbids sexual relations between blacks and whites. Schadeberg was outraged and spoke out publicly. A newspaper printed his story and afterwards none of his white colleagues wanted to speak to him anymore.

As his career progressed, Schadenberg began to report on apartheid with Drum investigative journalist Henry Nxumalo. They wrote about the inhumane treatment of blacks on "boer" farms owned by whites. The word "boer" stems from a Dutch or Afrikaans word meaning farmer and was a term used by white, conservative Africans to separate themselves from the black African population. Nxumalo infiltrated one of these farms, posing as a worker. The duo wrote about the demolition of Sophiatown and about the work of the African National Congress (ANC), which fought against the system and the racial laws.

First encounter with Nelson Mandela

Schadeberg met Nelson Mandela for the first time in 1951, when Mandela was president of the ANC Youth League. "He was actually fairly withdrawn as well. I thought that was very interesting. He had this certain aura that was very relaxing. He controlled the situation," Schadeberg said.

Nelson Mandela during the Treason Trial, 1958

They met many more times for photo shoots, but also just to talk, sometimes in an old print shop where the ANC printed flyers. In this print shop was an old oven where they hid a bottle of Cognac. At this time blacks weren't allowed to own or consume any kind of alcohol, according to the law.

Schadeberg says today that he didn't see his work back then as a political but rather as a human mission. But still, Nxumalo's and his work became increasingly difficult.

"Our people that worked for us would come back with a completely smashed face every now and again, because the police simply beat them up. Because they were, somehow, too 'cheeky,' as the police put it."

In 1957 Nxumalo was stabbed to death in broad daylight. That's when Schadeberg knew it was time to go. The police were coming after him, and the oppression in the country had become increasingly unbearable. "You could just see it wasn't going anywhere from here. You could hope that things would change, but nothing did change, and instead things became worse and worse," he said. In 1964 Schadeberg hid the negatives of his photographs and left South Africa.

Back to Europe

In 1964 Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment by the South African government, who labelled Mandela a violent communist agitator and convicted him of sabotage and initiation of guerilla war against the government. Mandela spent the next 26 years of his life in a prison cell on Robben Island, an island west of the coast of Cape Town.

Over the next few years, Schadeberg worked as a photographer in London, Germany, Spain, New York and France. He got married, worked for well-known magazines in Europe and the United States and taught photography in London and Hamburg.

But in 1985 he was drawn back to South Africa. When Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, Schadeberg celebrated New Years Eve with him in a house that was specifically built for Mandela in Soweto, an urban area of Johannesburg. Mandela's wife Winnie was cooking for the guests. "So we sat together and talked about the 1950s," Schadeberg said.

Schadeberg was on hand to nervously witness the first general elections in South Africa. "Some people were standing in the sun for hours just to vote. A white lady was standing next to a black maid, and for the first time they could freely have a conversation. It was a completely new atmosphere," he said.

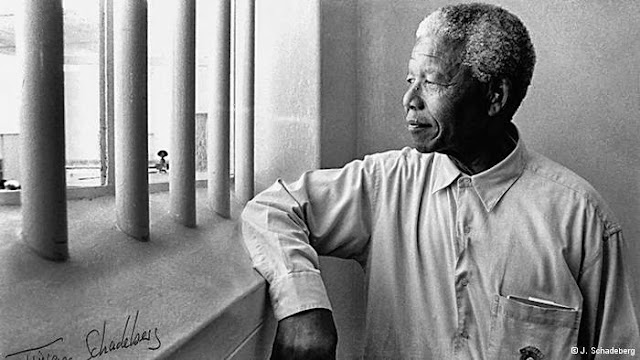

After being elected South Africa's first black president, Neslon Mandela returned with Schadenberg to the cell where he had been imprisoned for nearly two decades.

The Nobel Piece Prize laureate Mandela won the 1994 elections along with the ANC and became the first black president of South Africa. Shorty afterwards he returned to his prison cell on Robben Island. Jürgen Schadeberg and his camera were with him. The photo Schadenberg took chronicled the event and went around the world.

In his photo series "Tales from Jozi" and "Voices from the Land," Schadeberg documented the poverty and unemployment in South Africa. In 2007 he returned to Europe and received the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the only federal decoration of Germany, which is also known as the Federal Cross of Merit.

Soon a new volume of photographs will be released in South Africa. Throughout nearly 300 pages, Schadeberg looks back on "six decades of South African history." Whether the 82-year old will return to South Africa one more time is still unclear. He now lives in Spain close to the city of Valencia. The people there remind him of his time in South Africa, because they are so happy and friendly.

No comments:

Post a Comment