Acrotholus audeti and Neurankylus lithographicus. (Digital photographic compositing. Evans et al, 2013). One of the pleasures of working closely with paleontologists is that I get to be “in the loop” about new discoveries even before they go to print in research journals. This is gratifying because it allows me to still keep a foot firmly in the camp of active science even though I am not currently engaged in the research for which my graduate training in ecology and microbiology prepared me. This piece is an example of artwork that was commissioned by Dr. David Evans to appear in press releases in order to boost public knowledge of his research, helping to spread the word through newspapers, television and digital media much farther than would publication solely in a scientific journal. This scene shows the newly described dome-headed dinosaur, Acrotholus, exiting a stand of giant Gunnera leaves and coming across a Neurankylus turtle soaking in a footprint of a hadrosaur that had passed by earlier. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Carcharocles megalodon snacking on Platybelodon in Miocene waters. (Photographic compositing. Hall of Paleontology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, 2012). One of 14 of my images appearing as backlit panels (about 4 feet tall) in the museum, this image depicts the probably rare but plausible encounter between the giant shark Carcharocles (jaw diameter estimated at 11 feet) and a medium-sized proboscidean, Platybelodon. Whereas adult sharks likely dined over deep water, relegating their young to the safety of nurseries in shallow lagoons, it is plausible that an adult could enter shallow water occasionally, especially under stress. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Suchomimus and Kryptops. (Digital Painting, 2013). A Cretaceous Nigerian scene depicting a young (and speculatively feathered) abelisaurid called Kryptops disturbed from its drinking by the commotion caused by a Suchomimus plucking a young Sarcosuchus from its river habitat. This image was meant to break the unnecessary custom of nearly always showing the crocodilian-like snouted Suchomimus hunting fish of one sort or another. I do not see why it could not have hunted anything of about the right size, even a young Sarcosuchus (which, in adult form, would turn the tables and pose a greater threat to Suchomimus than the other way around). JULIUS CSOTONYI

Utahraptor attacking Hippodraco in sand dewatering feature. (Digital painting. Dr. James Kirkland, 2013). This image endeavors to restore some of the events leading to the creation of a large block of highly fossiliferous sandstone (containing Utahraptor over a range of ontogenetic stages and Hippodraco) from the Cretaceous in what is now Utah. The futile struggles of a Hippodraco draw the interest of a pack of Utahraptor , all of which will ultimately become mired in the quicksand. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Dimetrodon dawn. (Digital painting. Gondwana Studios, Australia, 2011). One of two marketing images created for Gondwana Studios’ travelling exhibit, “Permian Monsters: Life Before the Dinosaurs”. This image shows a lone Dimetrodon ready to begin sunning itself on an early Permian morning. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Lythronax investigating Squalicorax. (Photographic compositing, 2013). On a beach in Laramidia during the Cretaceous, in what is now Utah, a pair of Lythronax argestes moves in to investigate the stranded carcass of a large Squalicoraxshark, which is already being picked at by a pair of enantiornithine birds. Although protofeathers are not known from Lythronax, phylogenetic bracketing suggests their presence in tyrannosaurids in general, so I chose to give Lythronax a stubble of downy feathers. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Early Permian landscape. (Photographic compositing. Gondwana Studios, Australia, 2011). One of eleven murals created for Gondwana Studios’ travelling exhibit, “Permian Monsters: Life Before the Dinosaurs”. This image features the bizarre sight of Meganeuropsis carrying Hylonomus, and Eryops leaping after them.

JULIUS CSOTONYI

JULIUS CSOTONYI

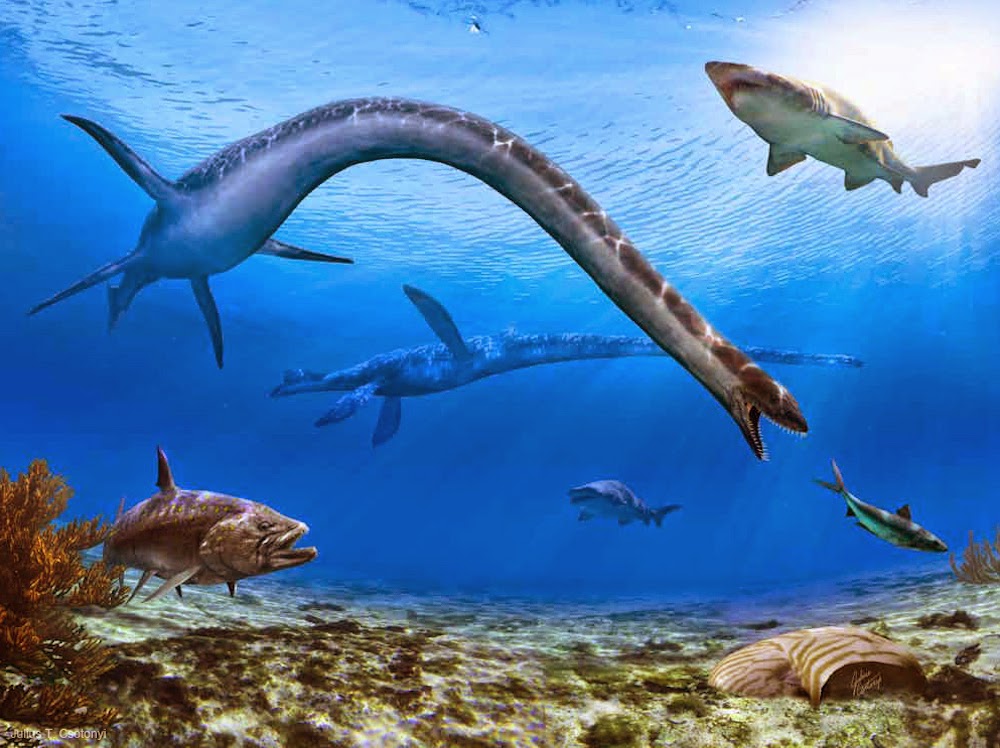

Albertonectes in the Bearpaw Sea. (Digital photographic compositing. Pipestone Creek Dinosaur Initiative in support of the Phillip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum, Grande Prairie, Alberta, Canada, 2012). It’s been rewarding to be involved in the fund raising efforts of Brian Brake’s team on the way to making a long-awaited dream come true: the building of Canada’s newest paleontological museum, the Phillip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum, just off the Alaska Highway. This piece, commissioned to be sold as prints for fund-raising, depicts the extremely long-necked plesiosaur, Albertonectes, hunting fish in the Bearpaw Sea, a Late Cretaceous environment of the Western Interior Seaway that once covered much of Alberta and that is an exceptionally well known paleo-ecosystem from the fossil record. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Permian dicynodonts. (Photographic compositing. Gondwana Studios, Australia, 2011). Created for Gondwana Studios’ travelling exhibit, “Permian Monsters,” this image features a group of the synapsid Dicynodon warily eying the early archosaur Archosaurus as it snaps up a breaching Saurichthys, while a Chroniosuchus hangs out in the stream shallows. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Mei long, first published specimen. (Digital painting. Non-commissioned, 2007). An illustration of the first published specimen of the troodontid Mei long, a name which in Chinese means “sleeping dragon.” It comes from the Yixian formation in China, amazingly in a posture similar to that adopted by sleeping birds of today. In this reconstruction, I wished to illustrate the concept of cryptic coloration, referring to the color patterns of an animal closely matching those of its surrounding, and which is employed by modern animals to hide from predators or prey. It would have been a useful trait for small theropods that slept on the ground, unless they had other means of hiding, such as inhabiting burrows or other concealing cover. JULIUS CSOTONYI

Damn Awesome!!

ReplyDeleteMagnifique! Really stunning.

ReplyDeleteExcellent pictures - worthy of Zallinger.

ReplyDelete