Not Anymore

American 'freedom fighter' Matthew VanDyke releases film on Syria

Fri, 09/20/2013 - 13:51

Caroline Clarkson

Last week, following considerable online buzz, self-styled “American freedom fighter" and documentary filmmaker Matthew VanDyke released the short film he has directed about the conflict in Syria. You may remember VanDyke from the civil war in Libya, where he fought on the side of the rebels. Captured by Gaddafi’s soldiers and thrown in jail, he spent almost six months in solitary confinement. Close to suicide, he only escaped when the guards abandoned his prison and a fellow inmate broke the lock on his cell.

This time, in Syria, VanDyke decided to shoot with a camera, not a machine gun. In late 2012, at considerable personal risk, he travelled to Aleppo, one of the cities worst hit by the civil war. There he met members of the rebel Free Syrian Army and shot the 14-minute film "Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution". He has now released the film on YouTube, weeks ahead of schedule. It is doing the festival circuit and has already picked up over a dozen awards, including the Audience Favorite Documentary Award at the Palm Springs International ShortFest.

“Not Anymore” features two charismatic protagonists: a young woman named Nour, who was an English teacher before the war but has now picked up a digital camera to document the conflict, and an FSA rebel fighter called Mowya, who has previously been arrested and tortured by Bashar al-Assad’s forces. It is impossible not to emphasise with the two young Syrians and VanDyke's film is extremely moving.

The 34-year-old says on his Facebook page he is releasing the film “so that people around the world can understand who the Syrian people are and why they are fighting for their freedom”.

Perhaps the film's only flaw is that it portrays the conflict as a somewhat simplistic “regime forces vs. rebels” equation. Today, the rebels have been considerably infiltrated by hardline elements. A recent report by IHS Jane's, a defence consultancy, estimates that nearly half the rebel fighters are now aligned with jihadist or hardline Islamist groups. Earlier this week, near the Turkish border, the al Qaeda front group ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) actually clashed with the FSA for the first time. But in a 14-minute film made in one city, it is obviously impossible to give a complete picture of a complex civil war.

“I spent everything I had on this film and I am in financial debt as a result”, VanDyke says on his Facebook page. It is unclear how he will be able to benefit from the film financially, having released it for free. In any case, he is asking his fans to “aggressively share” it on social networks. “Don't just watch the film, USE the film, day after day, week after week, to improve the image of this revolution and gain international support for it”, he urges. VanDyke is hoping that with sufficient press coverage, the film “could go viral similar to Kony 2012 and have a huge impact on world opinion of the Syrian revolution”.

Earlier this month, when Western military action against Syria appeared likely, VanDyke began mailing DVDs of his film to members of Congress in a bid to convince them to back military strikes against the Assad regime. But that option is now off the table.

Leonardo da Vinci

Below, a few fun facts from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com

Mona Lisa is mostly happy, a little bit disgusted. Discovery Magazine reported on research on the painted lady's notoriously coy expression. Apparently "researchers at the University of Amsterdam and the University of Illinois used face-recognition software to determine that the Mona Lisa is 83% happy, 9% disgusted, 6% fearful, and 2% angry."

Leonardo Da Vinci, an accomplished lyre player, was first presented at the Milanese court as a musician, not an artist.

Image:

Study of horses

circa 1490

Silverpoint on prepared paper

Ever the animal rights enthusiast, Leonardo Da Vinci reportedly enjoyed purchasing caged birds so that he could set them free.

Image:

The Virgin of the Rocks

Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo were reportedly frenemies. In "The Lost Battles: Leonardo, Michelangelo and the Artistic Duel That Defined the Renaissance," Jonathan Jones writes that two rival artists would often cause serious reality show level drama by insulting each other in public.

Image:

La Scapigliata

Da Vinci was the first person to explain why the sky is blue. (Light scattering, duh.)

Image:

Lady with an Ermine

oil on panel

Leonardo Da Vinci was also dyslexic, and had trouble reading, writing and spelling. (Luckily his drawing skills weren't too shabby.)

Image:

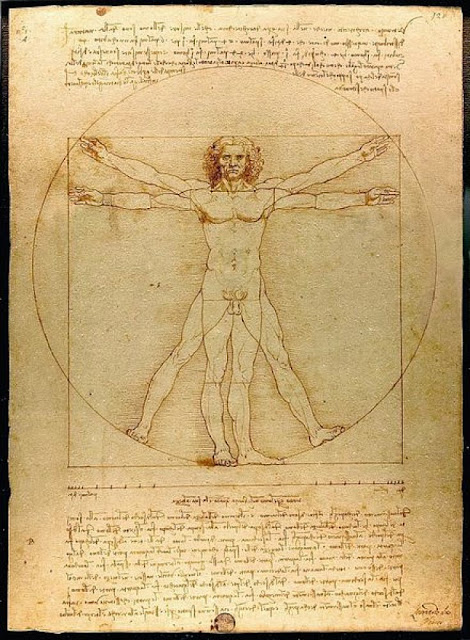

Vitruvian Man

Sun Straight Up Exploding All the Time This Weekend

X1 solar flare erupts from sunspot AR1875 on Oct. 28, 2013, GMT

The Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration (LLCD) aboard NASA's LADEE mission, fired its data-laser data downlinking an astonishing 622 Mbps and an error-free upload rate of 20Mbps.

Credit: NASA / LADEE

An X1.0 flare at 10:03 p.m. ET on Oct. 27, 2013 (131 Angstrom wavelength). NASA/SDO

BY Adam Mann 10.28.132:36 PM

http://www.wired.com

Our local star was active all weekend long, producing three of the most intense solar flares possible in two days.

The sun is currently at the peak of its natural 11-year solar cycle, where it oscillates through periods of low activity — characterized by few sunspots and intense flares — and much higher activity. This particular solar cycle has been one of the quietest on record, with the sun occasionally even going completely silent just as its activity should be highest. This weekend’s flares are a return to the normally scheduled intense outbursts from the solar surface that typically characterize solar maximum.

The first flare, which occurred on Oct. 25, was classified as an X1.7 class flare. An X-class flare is the strongest category of solar flare, where massive amounts of radiation spew from the sun’s surface. If this radiation is directed at Earth, it can mess with satellite communication, create radio blackouts, and generate beautiful auroras. An even more intense flare, an X2.1 flare, burst from the sun seven hours after the first on Oct. 25. An X2-class flare is twice as intense as an X1. A third flare X1-class occurred on Oct. 27 and at least 15 additional lower M-class flares happened between Oct. 23 and Oct. 28.

Marcia Wallace

The 8 Sassiest Quotes From “The Simpsons”’ Edna Krabappel

In memory of voice artist Marcia Wallace, who has died.

posted on October 28, 2013 at 10:24am EDT

Dan Martin

1. On romance.

2. On motivation.

3. On managing expectations.

"Some of you may discover a wonderful vocation you’d never imagined. Others may find out life isn’t fair; in spite of your Masters from Bryn Mawr, you might end up a glorified babysitter to a bunch of dead-eyed fourth graders while your husband runs naked on a beach with your marriage counsellor."

4. On consequences.

5. On priorities.

6. On being a glass-half-full person.

7. On knowing when to let them win.

"Well class, the history of our country has changed again, to correspond with Bart’s answers on yesterday’s test. America was now discovered in 1942 by ‘some guy.’ And our country isn’t called America anymore. It’s called Bonerland."

8. On the realities of life as an educator.

Ghosts

The Truth That Creeps Beneath Our Spooky Ghost Stories

by NPR STAFF

October 27, 2013 7:46 AM

Weekend Edition has been asking you to share your scary stories, the ones that have become family lore. This week, we're sharing those stories and delving into how and why they affect us.

As a teenager, Kevin Burns babysat for his sister's daughters — a 6-year-old and a 9-year-old. Throughout the night, he heard a baby crying, but it wasn't the kids, who were sound asleep in their beds.

Each time he investigated the crying, it stopped. When his sister and her husband came home, he asked them if their neighbor had a baby who cried loudly.

"Both of their faces instantly blanched white. They told me at that time that the house was haunted," Burns says. "They got a great deal on the house — they'd bought it, like, a month and a half before — and they were in the process of selling the house. And sure enough, within about another month, they were out of there."

Burns says he has a background in science and he doesn't really believe in ghosts, but the look on his sister's face gave him the willies.

The Unexplained Spooks The Skeptical

"Ghost stories are one of those things that have never been proven — but have also never been disproven, right?" anthropology professor Tok Thompson says. "Science can't really disprove ghosts exist."

Thompson teaches a class on ghost stories at the University of Southern California. The class explores the role of ghost stories in storytelling around the world and how they invite discussions of the soul and the afterlife.

Singer-songwriter Rita Hosking grew up in a house she says was haunted. She even saw the ghosts of a mother and her son, she says.

He says most polls find that a little more than 50 percent of Americans believe in ghosts.

"That's fascinating, because most Americans tend to believe in science. And even those who might not believe in certain aspects of science — say, evolution or whatnot — tend to be influenced by their religious teachings," Thompson says. "Well, here's a case ... where most Americans believe something that both their science and their religious leaders tell them not to believe."

Ghosts Are No Big Deal For Believers

Perspectives abroad can be different, though. Take Vietnam, where Ryan MacMichael was visiting his wife's family. One night, he says, a ghostly figure shook him awake and pointed to the bathroom.

"I thought maybe it was one of my wife's cousins had come in and woken me up," MacMichael says. "But first of all, it was three in the morning. Second of all, why would they do that? And third of all, when I had gotten up and left, I had to unlock the door to my room. It was still locked."

When he told his wife's family the story the next morning, they were pretty blasé, telling him it was probably Grandpa's ghost, just there to help him.

Thompson says that in many East Asian countries, belief in ghosts is not only more acceptable, "it's sort of unacceptable not to believe in ghosts."

He also notes that helpful ghosts are a common theme in these stories, particularly family ghosts.

A Creepy, Recurring Theme: Possessed Dolls

Thomas Adkins says he and his mom were visited many times by a Patti Playpal doll that would walk around the house, opening and shutting doors and flicking lights on and off.

"I would be in my top bunk, and I would hear in the middle of the night these footsteps coming and I would hear the 'thunk, thunk' up the ladder at the foot of my bed," he says. "I would see this doll's bangs and then her eyes peer over the edge of my bed and be so terrified that I couldn't even get a scream out."

The word "doll," Thompson says, actually comes from the root "idol."

"So this idea of their possessing a spirit, to some degree, is at the root of dolls," he says.

What Ghosts May Really Be Telling Us

Is there a point to ghost stories beyond instilling fear? Thompson says there must be some value to them.

"If there wasn't value in them, people wouldn't keep telling them. Frankly, I think that ghost stories deal with a lot of issues — not just whether or not one believes in ghosts, but also questions of the past that haunt us, perhaps past injustices that haven't been taken care of," he says.

Take the common theme of building on top of an Indian burial ground, for example.

"That speaks somewhat to America's history of the destruction of Native American peoples and societies that maybe hasn't quite been dealt with," Thompson says. "Or, again, we have a lot of ghosts of slavery."

"There's a lot of, I think, social and even moral messages that can come from ghost stories," Thompson says.

Bolivar Arellano

Photographing Puerto Rican New York, With A 'Sympathetic Eye'

by DANA FARRINGTON

October 26, 2013 5:06 PM

In the raging 1970s, New York City was dangerous, broke and at times on fire.

Latinos in the city were taking to the streets, running for office and carving out artistic spaces. "Latino" at the time in New York meant "Puerto Rican."

Photojournalist Bolivar Arellano immigrated to the city in '71, and remembers a vivid introduction to the Young Lords, a militant organization that advocated for Puerto Rican independence.

A member of the Young Lords with blood on his face is arrested by police. Bolivar Arellano took this photo, now on display at Columbia University, in 1971.

Dana Farrington/NPR

"Viva Puerto Rico libre!" Arellano heard a man shout next to a police officer. "Long live free Puerto Rico," was not a sentiment the officer shared. The man was hit with a baton after each declaration — six times, Arellano says.

"Blood was coming to his face, and that's when I said, Puerto Rico has to be beautiful for this guy to resist that beating," Arellano says. "So that was my encounter with the Puerto Rican community. Since then, I'm still with them."

This self-described activist-photojournalist chronicled the Latino community for El Diario-La Prensa, which also aimed to tell the stories the English-language press wasn't covering.

The Spanish-language daily is marking its centennial this year and is placing 5,000 archival images in Columbia University's care for preservation. Twenty of Arellano's black-and-white photos from the 1970s are now on display at the university.

"The Raging '70s" exhibit, which opened this month, positions vibrant musicians against militant activists — applause alongside protest chants. Celia Cruz onstage at Madison Square Garden. Alleged robbers in police cars after a blackout. Drug-dealing in public space. A re-creation of daily life on the Lower East Side for a film, a pig roasting in the foreground.

Arellano's work captures these moments in all their complexity, pulling you into specific places and times that are beautiful and at times tragic.

The photos show a history, but they also disrupt a familiar storyline of poverty and hardship. Arellano says he purposefully wanted to capture the joy of the Latino community.

The photos in Arellano's exhibit uphold the paper's claim of being "campeón de los hispanos," or champion of Hispanics.

Erica Gonzalez, the executive editor of El Diario-La Prensa, says the paper "has been forced to take up the banner of advocacy" because of the challenges its readership has faced.

Arellano's photographs, along with the rest of El Diario's archival images, will now be housed in the university's Latino Arts and Activism Collection at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A Profile Of The 1970s

For the exhibit, Columbia professor Frances Negrón-Muntaner sifted through dozens upon dozens of Arellano's photos to "map" the 1970s.

"I mean, really, this is a generation that produced salsa, a generation that produced experimental jazz, a generation that produced Nuyorican poetry and institutions that are still standing, and that not only harbored or housed them but also changed the ways we think about art and about audiences," she says.

The Nuyorican movement of the 1970s was a fusion of Puerto Rican culture and New York identity. Columbia adjunct professor and journalist Ed Morales says it reflected an "absorption of influences," combining English language with cultural aspects of Latin America.

Miguel Piñero of the Nuyorican literary movement and poet Sandra Maria Esteves on the train in New York City in 1977.

Bolivar Arellano

A prominent figure in that movement was Miguel Piñero, co-founder of the Nuyorican Poets Café. Arellano captured Piñero in a candid, lighthearted moment with poet Sandra Maria Esteves on the subway.

Move along the gallery wall, and you're confronted with "La Calle," the street. "You had the ways that people start owning the street," she says, "the way they start occupying it."

A front page of El Diario in 1977 declared: "Boricuas Ocupan Estatua Libertad." Activists occupied the Statue of Liberty to protest the incarceration of Puerto Rican nationalists. The takeover lasted more than eight hours.

The Young Lords also took on the daily needs of local communities. Another headline in the mid-'70s read, "Hispanos del Sur del Bronx, El Barrio, Brooklyn, Viven Entre la Basura" (Hispanics of the South Bronx, Spanish Harlem and Brooklyn Live Amid Garbage). The fight for municipal services, like trash collection, was a trademark of the era.

Arellano's photos span the "richness and the range of the '70s politics," Negrón-Muntaner says.

In 1970, Herman Badillo became the first Puerto Rican congressman, representing New York's 21st District in the South Bronx. Though he never successfully took the Democratic nomination for mayor, Badillo served in various city positions, including deputy mayor.

Arellano also photographed Juan Mari Brás, who advocated for Puerto Rican independence and founded the Puerto Rican Socialist Party.

An image of Brás joining hands with Black Panther Angela Davis at a unity protest in Madison Square Garden is next to Badillo in the exhibit.

Sensing The Moment

Leaning in close, gesticulating with his hands and eyebrows, Arellano says he spent long hours covering news, sports and entertainment. He remembers a time when journalists moved about the city with ease, capturing intimate moments in hospitals, on the streets and backstage at high-profile venues.

He spent his days listening to a police scanner he bought, taking activists' tips on upcoming protests and combing The Associated Press daybook for events. He put in 16-hour days and filled El Diario's pages with his photos. He learned the language, too ("The New York Times is the best book to learn English").

Arellano insisted there is no signature style to his photography; he never had any formal training. He just shoots what catches his eye.

But there is something that distinguishes his work, according to Negrón-Muntaner. "When you look at these pictures, you really get a sense of the moment," she says. The photos convey the dynamics and the tension of the time, she says, whether it is between the police and a protester or between a performer and her audience.

As an immigrant, he had a "sympathetic eye" while photographing the Latino community, Negrón-Muntaner says: "There seems to be a relationship or an intimacy or an access that the photographer is able to communicate."

There is a nuance that is often missed by outsiders who might only focus on poverty and devastation, says David Gonzalez, co-editor of The New York Times Lens photography blog.

"His pictures reflect the complexity and the dynamism that was happening in the various communities of New York City," he says. Gonzalez wrote about Arellano and his work in June and considers him "one of the stalwarts of New York photojournalism."

El Diario has similarly made nuance a priority in its coverage over the years. Executive editor Gonzalez says they analyze the dominant narrative of a story and then add something to the conversation. "El Diario has really brought depth to this community," she says.

Arellano says he didn't need to focus on the negative aspects of Latino life because everyone else was already doing that.

"I was covering the good things about the Latino community," he says. "There was nobody covering the good side."

History In Shambles

Arellano never intended to show his photographs in a gallery. As a freelancer, he was working one shot at a time.

"You have no idea how I [mistreated] the negatives," he said amid the photos that somehow survived the decades since. Over the past seven years, he has been digitally archiving his tens of thousands of photos.

And yet, without the pictures that Arellano has managed to save, there wouldn't be a '70s exhibit for El Diario's centennial.

Javier Gomez was hired as a consultant by the paper to organize its 100th anniversary, which includes a series of events and coverage focused on legacy, education and preservation. They wanted to do a photo exhibit from the beginning.

"So we opened the archives to do an assessment to do a centennial exhibit of 100 years of Hispanic history — we realized that we only had 30 [years' worth]," Gomez says. "We couldn't believe it."

Practically all of the photos before the 1980s were completely ruined. There had been a flood at a previous location in lower Manhattan, then two moves. The paper decommissioned the archive when it switched to digital, leaving the images without oversight. Some photos were stolen and others misfiled.

"Laughable and terrifying at the same time," Gomez found stacks of images glued together.

"As we were reviewing them for the exhibit, we pulled some carefully, trying to open them like leaves in a book," he says. "We had to let it go. That's for experts to deal with."

Enter Columbia University. "We're very happy and very proud to get these to an archive," Gomez says. The university plans to index and digitize the thousands of images that were recovered, preserving them for El Diario-La Prensa and for the city.

After all, as the paper's executive editor put it: "We're not just a Spanish-language, Latino institution; we're a New York institution."

Washington Heights Exhibits

Additional photos from El Diario's archive are displayed in three locations around the city as part of a series called "In the Headlines: Latino New Yorkers 1980-2001."

At the Medical Center exhibit on 168th Street, the display of images and front pages blends with the educational environment. The photographs are familiar to the building's security guards who live in the neighborhood. It's fitting to hear Spanish spoken in the hall.

A part of the El Diario centennial exhibit series, at the Columbia University's Medical Center.

Dana Farrington/NPR

"There's a kind of beauty ... in that anguish that I was trying to capture," says curator Rich Blint, associate director of Columbia's Office of Community Outreach and Education.

War of the Worlds & Wait Wait...October 26, 2013

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In RadioLab's very first live hour, they take a deep dive into one of the most controversial moments in broadcasting history: Orson Welles' 1938 radio play about Martians invading New Jersey. "The War of the Worlds" is believed to have fooled over a million people when it originally aired, and it's continued to fool people since--from Santiago, Chile to Buffalo, New York to a particularly disastrous evening in Quito, Ecuador.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When Orson Welles decided to make a radio play of the H.G. Well’s classic, "War of the Worlds," he had no idea that he would be branded by the FCC as a "radio terrorist." The audience reaction - panic on a mass level never before witnessed – isn’t just a testament to Welles’ talent for gripping drama, it’s also a reflection of that moment in history. RadioLab takes a close look at the way that the evolving news media collaborated with the events in Europe to prime the pump.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RadioLab takes an in depth look at a War of the Worlds radio play incident with even more dire consequences. In 1949, when Radio Quito decided to translate the Orson Welles stunt for an Equadorian audience, no one knew that the result would be a riot that burned down the radio station and killed at least 7 people. Reporter Tony Field takes us to Quito to finds out what really happened. But RadioLab would have hardly have decided to dedicate an hour to this if it was only a two-time occurence. That’s right: it happens again. This time it’s in the 1960s in Buffalo, NY. Why does this keep happening? RadioLab talks to psychology professor Richard Gerrig who tells us that the answer may have to do with RadioLab's natural response to stories.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To get some insight into what would make a person want to fool their audience, RadioLab talks to Daniel Myrick. Myrick, with Eduardo Sanchez, made a film called "The Blair Witch Project," which terrified its way to cult success and convinced a few people to never go camping again. RadioLab also talks with Jason Loviglio, a media historian, about how the soothing tone of FDR’s fireside chats, mirrored in the wartime reporting of Edward R. Murrow may have been the true target of Orson Welles’ adaptation of War of the Worlds. And in an ironic twist, the news media fully embraces Orson Welles greatest insight into broadcasting. It’s a truth so terrifying you won’t want to miss it: if the audience is scared, they will keep listening.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Brave Genius

Excerpt

Brave Genius

by Sean B. Carroll

Prologue

CHANCE, NECESSITY, AND GENIUS

Genius is present in every age, but the men carrying it within them

remain benumbed unless extraordinary events occur to heat up and

melt the mass so that it flows forth.

—Denis Diderot (1713–1784), “On Dramatic Poetry”

On October 16, 1957, Albert Camus was having lunch at Chez Marius in Paris’s Latin Quarter when a young man approached the table and informed him that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The new laureate- to-be could not hide his anguish.

Sure, the Algerian- born French writer had been an international figure for more than a decade. He had earned great public admiration for his moral stands as well as for his novels, plays, and essays. But not yet forty-four years old, Camus was only the second youngest writer ever to receive the Nobel. He thought that the prize should honor a complete body of work, and he hoped that his was still unfinished. He dreaded that all of the fanfare surrounding the prize would distract him from his work. The demand for interviews and photographs, and the many party invitations that followed the announcement soon confirmed his fears.

Camus also worried that the prize would inspire even greater contempt on the part of his critics. Despite his public popularity, Camus had many foes on both the political right, to whom he was a dangerous radical, and the left, among them many former close comrades who had ostracized him for his clear- eyed, damning critiques of Soviet- style Communism. Both camps took the Nobel as proof that Camus’s talent and influence had already peaked.

“One wonders whether Camus is not on the decline and if . . . the Swedish Academy was not consecrating a precocious sclerosis,” wrote one scornful commentator.

After the demand for interviews subsided, he paused to reply to a few well wishers. One handwritten letter was to an old friend in Paris:

My dear Monod.

I have put aside for a while the noise of these recent times in order to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your warm letter. The unexpected prize has left me with more doubt than certainty. At least I have friendship to help me face it. I, who feel solidarity with many men, feel friendship with only a few. You are one of these, my dear Monod, with a constancy and sincerity that I must tell you at least once. Our work, our busy lives separate us, but we are reunited again, in one same adventure. That does not prevent us to reunite, from time to time, at least for a drink of friendship! See you soon and fraternally yours.

Albert Camus

Camus knew well many of the literary and artistic luminaries of his time, such as Jean- Paul Sartre, George Orwell, André Malraux, and Pablo Picasso. But the recipient of Camus’s heartfelt letter was not an artist. This one of his few constant and sincere friends was Jacques Monod, a biologist. And unlike so many other of Camus’s associates, he was not famous, at least not yet. However, despite his pantheon of numerous, more illustrious colleagues, Camus claimed, “I have known only one true genius: Jacques Monod.”

Eight years after Camus, that genius would make his own trip to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with his close colleagues François Jacob and André Lwoff.

Each of the four men’s respective prizes recognized exceptional creativity, but they also marked triumphs over great odds. The adventure to which Camus referred in his letter began many years earlier, in a very dark and dangerous time. So dangerous, in fact, that the chances each of these men would have even lived to see those latter days, let alone to ascend to such heights, were remote.

This is the story of that adventure. It is a story of the transformation of ordinary lives into exceptional lives by extraordinary events— of courage in the face of overwhelming adversity, the flowering of creative genius, deep friendship, and of profound concern for and insight into the human condition.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Review

‘Brave Genius’ Is a Story of Science, Philosophy and Bravery in WartimeBy JENNIFER SCHUESSLER

Published: October 21, 2013

http://www.nytimes.com

These days, science and philosophy don’t seem to be the best of friends. Some prominent scientists dismiss philosophers as chasing vague concepts into “murky and inconsequential” rabbit holes, as the physicist Steven Weinberg once put it. And philosophers accuse scientists of imperial overreach in their attempts to claim ultimate authority on questions like consciousness, free will and the existence of God.

But in “Brave Genius,” Sean B. Carroll tells the interlocking stories of a philosopher and a scientist, Albert Camus and Jacques Monod, who were not just passionate friends but sometimes seemed to be living two versions of the same life. Both were active in the French Resistance during World War II, and after the war both devoted themselves to fighting the intellectual corrosions of Communist ideology. Both men won the Nobel Prize, Camus for literature and Monod for physiology, in recognition of fundamental discoveries about the regulation of gene expression.

And the similarities run even deeper. Both Camus and Monod, Dr. Carroll writes, were concerned with the same fundamental problem: how to act morally, even heroically, in a random, indifferent universe.

Camus, whose 100th birthday is being commemorated this year in France, will be the marquee attraction for many readers. Dr. Carroll, a molecular biologist, occasional contributor to Science Times and onetime college French major, tells his story crisply if somewhat dutifully — from Camus’s early days as a journalist through his first literary success with “The Stranger,” his rise to global fame and his premature death in a car crash in 1960, at age 46.

But Monod, whose name will ring few bells among nonscientists, comes off as the far more swashbuckling and intriguing figure. Born in 1910, he joined the Resistance as a young researcher at the Sorbonne (where he liked to hide sensitive documents inside the leg of a mounted giraffe outside his office), eventually rising to a top position in the main national Resistance network. While Camus was writing anonymous editorials for the Resistance newspaper Combat, Monod was organizing the sabotage of rail lines and, in one particularly suspenseful episode reconstructed by Dr. Carroll, evading the Gestapo by going underground with a colleague posing as an artist. After the war, Monod returned to research at the Pasteur Institute, but found himself drawn back into politics. In 1948, he published a blistering front-page article in Combat attacking the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko as a pseudoscientist. The article — “a condemnation of the entire Soviet system of thinking and of its leadership,” Dr. Carroll writes — drew a firestorm of protest from France’s powerful Communist Party. It also brought Monod into the orbit of Camus, who drew on the scientist’s ideas for a chapter in “The Rebel,” his 1951 attack on totalitarianism.

“Brave Genius” is briskly paced and ambitiously sprawling, offering potted accounts of historical episodes large and small (the fall of France, the 1956 Hungarian crisis, Camus’s famous feud with Jean-Paul Sartre, the discovery of the double helix), along with finer-grained descriptions of Camus’s and Monod’s work.

Dr. Carroll has done some impressive archival digging, turning up fresh and often vivid details about Monod’s dogged efforts to smuggle dissidents out of Hungary at a time when his scientific work was at full pitch. One Hungarian scientist, in a bit of lab-inspired derring-do, sent Monod secret messages written in invisible ink made from starch, which turned blue when exposed to iodine solution.

But the book, written in an unwaveringly heroic key, never quite makes either man come alive from the inside, or conveys the substance of a friendship Dr. Carroll claims was one of the few “constant and sincere” connections in Camus’s life. He quotes some affectionate letters and book inscriptions traded by the two men. But he almost never shows them together, beyond the occasional vaguely invoked dinner party. (“Cold war politics were never far from their conversation,” he writes in a typically broad sentence.)

Dr. Carroll is much more successful at illuminating the deeper parallels between the two men’s work. Monod, in his view, was not only a brilliant researcher and a national moral conscience who stood with French students at the barricades in 1968 and spoke out on issues like birth control and racial equality. He was also “Camus in a lab coat,” a profound thinker who linked life’s deepest meanings to its hidden mechanics.

Monod’s discoveries, Dr. Carroll writes, helped provide the intellectual scaffolding for understanding “one of the greatest mysteries of biology: the development of a complex creature from a single fertilized egg.” In his 1970 book “Chance and Necessity” (a best-seller in France second only to Erich Segal’s “Love Story” for much of that year), Monod explained those discoveries for a popular audience, explicitly tying them to his friend’s existential philosophy.

“Molecular biology,” Dr. Carroll writes, “had brought Monod full circle to Camus’s territory of the absurd condition — that contradiction between the human longing for meaning and the universe’s silence.”

“Chance and Necessity” took its epigraph from Camus’s “Myth of Sisyphus,” thus repaying an earlier compliment from Camus that readers of “Brave Genius” may not find at all absurd: “I have only known one true genius: Jacques Monod.”

Professor Snape, a Great Friend

1. He has the best wardrobe to borrow clothes from.

2. He always remembers to compliment you.

3. He’s a man of words and action.

4. He sends you disapproving Snapchats to help you judge others when he’s not there.

5. He can bring a smile to literally anyone’s face.

6. He’ll make you be honest with yourself.

7. He’s comfortable just hanging out and not talking if that’s what you need.

8. He’s an avid reader and therefore brilliant.

9. But he’ll read the gossip rags and be like, “OMG look at her butt” with you.

10. He knows how to have a good time.

11. He won’t let anyone talk shit about you.

12. He’s your biggest cheerleader.

13. He won’t let you ruin your life or haircut on an irrational revenge driven whim.

14. He’s a trailblazer.

15. He will literally light up your world.

16. No, seriously, he fangirls just as hard as you do.

17. He gives the BEST hugs.

18. And you two will be best friends always.

Reasons Snape Is The BFF You Want And Need

Always…

October 21, 2013 at 3:08pm EDT

Krutika Mallikarjuna

About Writing

How To Write An Awesome Movie, According To Some Of Hollywood’s Best Writers

Hollywood pros like Paul Feig, Richard Linklater, and Diablo Cody give their best tips and insights for all you wannabe writers.

October 24, 2013 at 7:08pm EDT

Jordan Zakarin

All aspiring writers have experienced the conception of a story, that little atom of an idea that explodes into a vision of a journey in a big bang “aha!” that rattles the brain. But the difference between the daydreamers and actual filmmakers starts right after that revelatory moment, when the disparate strands of an idea either begin to take shape — and, at some point, migrate over to Final Draft — or just fade away.

BuzzFeed spoke with some of the industry’s top writers and directors to learn how they develop a tiny germ of an idea into award-winning screenplay. They discussed everything from how they get started, to how to sit down and write, and how to balance dialogue and structure.

Here’s the roster of advisers: Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise trilogy, Dazed and Confused); Paul Feig (Freaks and Geeks, Bridesmaids, The Heat); Diablo Cody (Juno, Young Adult); Richard Curtis (Love Actually, About Time, Four Weddings and a Funeral); Nicole Holofcener (Enough Said, Please Give); Michael Weber and Scott Neustadter (500 Days of Summer, The Spectacular Now); David Wain (Wet Hot American Summer, Role Models); Rian Johnson (Looper, Brick); Jeff Nichols (Mud, Take Shelter); Lake Bell (In A World); David Gordon Green (Prince Avalanche, Pineapple Express); Greta Gerwig (Frances Ha); Mark and Jay Duplass (Jeff Who Lives At Home, Cyrus); Nat Faxon and Jim Rash (The Descendants, The Way, Way Back); and Brian Koppelman (Rounders, Oceans Thirteen).

How Ideas Are Born…and Then Stashed Away in Drawers

Richard Linklater: There are a million ideas in a world of stories. Humans are storytelling animals. Everything’s a story, everyone’s got stories, we’re perceiving stories, we’re interested in stories. So to me, the big nut to crack is to how to tell a story, what’s the right way to tell a particular story. So I’m much more interested in narrative construction.

I have a lot of subjects I’m spinning around on that I like and I take notes and read books and have files of things that interest me, but it’s like, What is the movie? How do you crack it? So I like that search.

I think you have to be forever intrigued with the subject matter, the character, or something you’re digging into, you’re rummaging around, something that fascinates you. That process can’t really ever end. If that ends, the movie is over.

Jeff Nichols: I started thinking about Mud in college. [Nichols is now 34.] I’m a very slow writer, and the typing, which most people consider writing, that’s a very last step for me. I heavily outline things. Even before I write anything down, I think about things for a really long time. It’s like a tape ball that you just add detail to, and that’s what happened in this case.

If you’re a friend of mine in Austin, I’ll grab you and take you to lunch and I’ll just vomit this story at you. It’s a really good way to start working the story out. You start talking to people about it, and in the moment, you start to figure out things that connect and make things work, because you have to, because you have to keep telling your story.

Paul Feig: I’m big into notes. I always try to keep a small pad of paper in my pocket and write down any idea that seems interesting. I also type notes into my phone and computer. I basically have ideas written down everywhere. I’ve spent my life reminding myself that, even though I always tell myself I’ll never forget an idea when I think of it, I always forget it, sometimes a minute or two after I’ve thought of it. So, I always force myself to write any idea down. The downside is I have little notebooks scattered around the house and in storage boxes that I never think to look through. Not that any of the ideas in them are gold; most of them are pretty lame. But occasionally, I’ll find a few that link up and create the basis for something worth thinking about.

Diablo Cody: I envy writers who have their shit together! You should see my computer desktop. It’s like 9 million Final Draft documents, pictures of my kids, and photos of haircuts I wish I had.

Richard Curtis: One of my big rules, if I had any rules for screenwriting, would be to let things sit there and stew. Because the two times that I’ve written films, just thought of them and written them, have been the two times I’ve just put them in a drawer and never done anything with them again. So, on the whole, if you take About Time, I thought about the idea in one shape or form at the same time that I was deciding to do the Pirate Radio movie, and I needed a bit more time and a bit more wisdom. “About Time is a bit more serious, so I’ll wait.” So that one, I’ve waited five years.

I often think the fact that, as it were, I’ve written half the number of films I could have or should have done, has been to my advantage. Because I like to really live with an idea. A film is not a flirtation, it’s a relationship. I said to my girlfriend the other day, “The difference between having a good idea for a movie and a finished movie is the same as seeing a pretty girl across the floor at a party and being there when she gives birth to your third child.” It’s a very long journey, and my first idea doesn’t bear much relationship — there are lots of pretty girls at parties, but not many will be there when you have your third child.

David Gordon Green: I have a lot of journals of just notes of ideas or dreams or things like that I think would be movie-worthy. I try, every once in a while to go to my computer, and have a master file of strange things; that’s where the title Prince Avalanche came from, this weird list of things that I dreamed about. It’s more like a scrapbook kind of thing or I’ll have a cutout of things I’ll see in Sky Mall magazine or something that makes me think of something weird.

It’s like my therapy. I use my profession as my own therapy. It’s kind of sick, isn’t it? I made this movie and I think certain people who know me very well will find, not only elements of me, but relationships with them, words they’ve said in conversations with me, strange things that are directed toward them and only them. And I think that for people who are close to me, to see something in a movie that a large audience is watching, and knowing something that is so specific that would only be for one person.

Nicole Holofcener: I guess I let it marinate a little bit, and then, if I’m afraid I’m going to forget it, I write down some notes. And usually, I’d say about 95% of the time, once I see the notes written down, I realize it’s a bad idea, which is why I don’t make movies frequently, because I can’t come up with an idea that I think is good.

If I write it down and I don’t hate it, or I feel inspired to take more notes, and I look at it again and again, day after day, and build on it, and if I’m not embarrassed by it — just even by myself — then I think maybe I should pursue it and maybe I can write this. And around the time I get sick of taking notes, I’ll start typing the script up.

Mark and Jay Duplass: We have lots of story ideas. We keep an ongoing document full of story ideas, over 100 of them at this point. We don’t have very many half-written scripts because we usually don’t start writing something until we know exactly where it’s going and what all the story beats are. The actual “writing” of our scripts is a quick spring once we’ve figured out the entire structure (which can take a long time).

Creating a Structure

Linklater: You have to follow [a question] through production, post-production, and then some. If you can ever get into something and have it all figured out, then you probably shouldn’t make a film about it. Then, you’re done. The making of the film to me is the final exponent, the final piece of the puzzle that you’ve been working on. To me, the bigger part to the puzzle is really trying to crack the narrative back of it, how to tell the story.

Woody Allen’s films are all these accumulations of all his ideas. The way his particular genius is, these things are just flowing out of him 24/7. In so many of his films, he creates a unique narrative structure — like Deconstructing Harry — to hold this basketful of ideas that don’t have other homes. The out of focus actor? You don’t make a whole film about that, but you realize he’s not telling just one story; he’s creating structures to house all these disparate ideas. He does that over and over. That’s a narrative triumph, to find the housing for your particular idea.

Mark and Jay Duplass: We heavily outline before any writing happens. We used to use note cards, but now we’ve gone green. We have abandoned thoughts of three-act structure and differences in plot types, etc. We are trying to function more from our guts. Follow our instincts, get out of our heads.

David Wain: I always lay in a subplot around 10:30 in the morning. That’s by far the best time. The worst time is 4 p.m.

Cody: I know it’s a real idea when I turn into a crazy person and have to immediately lock myself in a room and write and ruminate for hours. It’s like A Beautiful Mind, but with bad dialogue instead of equations. My husband knows when I have a story going because I get really quiet. It’s all I think about until I’ve regurgitated every detail and shaped it into a draft. Obviously, I have ideas that aren’t as exciting to me, but if I think they have the potential to sell, I’ll write up a quick email and pitch it to my agent. Not as exhilarating, but it pays for preschool.

Feig: Usually, it’ll be something like, Hey, it’d be fun to write about this subject matter. What kind of characters would be the most interesting in this world? Structure is usually what comes last. I always want to figure out the characters and their personalities and then set them loose in the idea so I can see where they naturally take me. Then I play out the story and try to twist and turn it as much as I can.

I really block out every day. I kind of set aside from 9 a.m.–6 p.m. every day and just sit there. Sometimes, the writing process is going out and walking around or going out to have lunch and taking the computer with me. But it’s basically going, I’m just going to sit here and be open to whatever is going to come into my brain for this. And also, I always set a goal when I’m writing a screenplay: five pages per day. As long as I hit five pages per day, within 23 days or whatever, you will have a first draft.

Cody: I hate outlining, but the suits make me do it. Sometimes, I don’t like structure; I like telling a meandering story and letting the characters determine the outcome. I’ve been surprised by the ending of one of my scripts more than once. Like, when I was writing Juno, I was sure Juno was going to have sex with Mark, the Jason Bateman character. Then I got to that scene and realized, Oh shit, she doesn’t want to do that. So I switched directions. I can’t make all those decisions in advance. I don’t know who the character is until I’ve spent some time writing for them.

Curtis: I seem to remember the first instinct for Four Weddings and a Funeral came from that being, as it were, a subject I was interested in: how to find the right girl. That’s what I spent my twenties doing, so the fundamental subject was right. And then I thought, I’ve been to 70 weddings in the last three years, so I thought I’ve got lots of stuff around weddings.

And then there was a particular sort of structural instinct where I got very annoyed about films where you see a couple meeting and then you cut, and then they’d be going out with each other, and you’d think, What happened? And then they’d start going out with each other, and then you’d cut, and they’d be having a fight. And you go, What? And so I thought, Wouldn’t it be great to have a film where you saw every single minute a couple was together, apart for the six hours of sex? And if you look at that film, it’s sort of what happens. You see every single minute that Andie MacDowell and Hugh Grant spend together. So that was the sort of mixture between autobiography, jokes in terms of weddings, and a sort of structural idea.

Michael Weber and Scott Neustadter: We don’t write a word until the entire movie is thoroughly outlined. This document is just for us and it usually runs 8–10 pages. It’s simply a scene-by-scene map of story, character, transitions, important lines, and hopefully, a few good jokes. Any important subplots will be covered in this outline. Of course, there are always discoveries during the writing — which can include ways to improve the subplots.

There’s always crucial information that requires an elegant layering into the story. How to do that — and where to do that — that’s what the outline is for. In terms of jokes, well, here’s our dirty little secret: We’re not funny. We think we have a good handle on character and hopefully, we understand story. After that stuff is working, we can usually generate some comedy. But it never starts with gags or jokey callbacks.

Nichols: I start with note cards, so I write every idea I’ve had for a scene and everything else on a note card, and I throw them on the floor. It’s a good way to break up the linear process of it all. The problem is, when you’re literally writing an outline on a page, you’ve got to start somewhere, and then you have to go to the next thought, and you don’t always have that next thought, but you have all these other thoughts.

Slowly, they start to take form and shape and they go up on a cork board and before you know it, I could watch the whole movie on note cards before I even start writing.

Holofcener: I used to do [note cards], and it really just fucked me up. It would sort of kill the fun, and it would make me realize that I didn’t know how to structure a screenplay. Or I didn’t have the answers that you’re supposed to have when you outline a script, and I figured out somehow that I didn’t need to have the answers. And I would just start writing and see what happens, and usually, what happens is a mess, but a fixable one, and that’s kind of how I start.

I generally have no idea [where a story will end], at least consciously. With a script like Enough Said, I knew I wanted her to become a better person at the end, to learn a lesson, and shut off the judgmental voices in her head, but I didn’t know how that was going to happen or what that would look like.

Bell: When I start writing, I string together my favorite ideas, my greatest hits, and I start to figure out a road map for those people or those ideas and thoughts and thematics. And then the story, the overall umbrella of the story, sort of exists already, but then you kind of fit in these puzzle pieces in the thing you want to talk about.

Linklater: To me the dialogue comes kind of last. To me, the dialogue is the final coat of paint. My films are all dialogue, but I swear to god, that’s what you see at the end. You look at it and it’s that coat of paint. But to me, what fascinates me more is the architecture beneath it.

Knowing Your Characters

Brian Koppelman: That part of the process remains mysterious to me. And I’m glad it does. The less I am aware that I am thinking, and the more that the subconscious takes over, the better. I think I understand the characters and how they think. But again, none of that is conscious. Great impressionists talk about thinking at different speeds when doing certain voices. It’s like that. You just write from the characters perspective because in those moments, you are fused together (when it’s working, flowing, alive. The other times you feel like Barton Fink).

Mark and Jay Duplass: On the movies that we improvise, we spend a ton of time on backstory. On the ones we fully script, we don’t fuss too much over it.

Weber and Neustadter: For us, creating backstories isn’t as helpful as, say, asking what a real person would do in the situation and jumping off from there. If your character wouldn’t do what a normal person would do, then why not? What’s the deal with that? We’ve always found bringing it back to reality to be the most helpful tool with every project.

Feig: I think you pretty much have to play out all sides of your personality in your characters. Otherwise, I don’t think you’re truly able to know what they may or may not do. “Write what you know,” as the saying goes. As a writer, you tend to compartmentalize different parts of your personality so that you can pit those various personalities against each other in your head as you’re writing. It’s sort of the fun part of the process, the therapeutic part that can be more productive than therapy.

You just have to be very honest with yourself when you’re doing this so that you get true responses and decision making from each side of yourself. There’s an unconscious tendency a lot of us have to make characters do things that we’ve seen in other movies or television. So, you constantly have to ask yourself, Would I really do that? What would I actually do if I was in that situation? You’d be amazed how many times you end up calling bullshit on your first idea.

Lindsay Weir on Freaks and Geeks was always my favorite. She was the mouthpiece for who I really was at that moment in my life. I was a 35-year-old man and all the problems and insecurities and questions about life I was having fit perfectly into the mind of a mature 16-year-old girl. She wasn’t based on anyone I knew. She was basically the big sister I always wanted. (I was an only child.)

Wain: Lead character certainly need to be thought through all the way back so there’s a cohesiveness and depth to what is presented on screen. Although sometimes it’s interesting (or funny) to purposely leave certain questions unanswered.

Curtis: I think the leading character is the sort of model usually between me and my best friend Simon and the circumstances of that character, as it were. It’s very interesting how the other things occur to you. They’re very rarely based on anyone, but they’re aspects of people who have really interested you or touched you.

Sometimes, you start with a line. I think Emma Thompson’s character [in Love Actually] — I never thought this before, I never said it — came from a line in a novel. Someone in a novel finds out that her husband’s been unfaithful, and she suddenly realizes that who she is is a completely different person. Suddenly, in the course of one minute, and she hasn’t done anything. That was such an extraordinary bold thought, and then I built up my version of that, but that character was based on that one moment of discovering that your whole life has changed and you haven’t done anything, you’ve just unwrapped a Christmas present.

Feig: I start out many characters based on people I know or have met but then once you start mixing your personality into them and adjusting the characters to the story you’re telling, they start to get further and further away from the person who was the initial inspiration for them. Which is good because you never want somebody coming up to you and saying, “That bad guy was based on me, wasn’t he, you son of a bitch?”

I want their journey through the world to be what drives the story. I’ve always been less a fan of movies that are event-driven, meaning external events happening that our characters are then thrust into. I like my stories to be driven by the decisions my characters make. And so in order to do this, I have to know those characters pretty intimately so that I can be surprised by their decisions and let those decisions drive the story and relationships forward.

Holofcener: Definitely in Walking and Talking, at one point in my life, Catherine Keener’s character was very much me. So many things in that movie were kind of autobiographical, more than other movies. I guess, in Please Give, Catherine Keener’s character, not in all respects, but many respects. Eva, in Enough Said, I’m kind of all over the place. Sometimes I’m even the daughter of somebody. Like in Please Give, the daughter with the acne, she really felt like me, or I felt like her, when I was a teenager.

I feel like, well if I’m going to make fun of other people, I’m going to make fun of myself, and I always want to make fun of myself. If anything, that feels more cathartic than writing about other people, because I can show the world and myself that I know how inadequate I am, and that somehow I’m kind of forgiving myself a little bit. If I know I’m a really guilty person and I know that my guilt makes me act like an idiot half the time, it’s kind of entertaining to put it out there.

Cody: I relate to my characters, yeah, but at this point I’m hesitant to talk about it. Because for some reason — maybe because I’m female and chatty and accessible — everyone thinks EVERYTHING I write is completely autobiographical. It’s weird.

I like Jennifer in Jennifer’s Body! She had it all figured out. And I love Juno’s stepmom; she’s a badass. As for relating to a character, I think Loray (Octavia Spencer) in Paradise is an obvious extension of me. She has a lot of cool wigs and she drinks a ton.

Writing (Non-Expository) Dialogue

Greta Gerwig: I don’t mean this to be arrogant, but I can write dialogue all day. That’s my comfort zone. Making the dialogue count toward the story, I always resist it but then I love it when it’s in place; because I feel resistant, it almost feels like I’m forcing a structure on something that doesn’t want to have a structure.

Curtis: I mainly discover the people by writing how they talk. And I write very fast, so I write 20 or 30 pages a day. And I will just have people chat to each other. And I’ll have a chat that will sometimes turn into a scene that is in the movie, but sometimes it’ll just be random conversation and I get a feeling for how they talk to each other and how they interact, and I’ll have long conversations between people — in Four Weddings, I would have had all of them spending a lot of time with each other, even though in the movie I mainly have them spending time just through Hugh. That refines them. I could have written Notting Hill in four days, but it took me 300. What happened to the other 296 days of dialogue?

Feig: I say [dialogue] out loud. If I can’t say it and make it sound convincing and not clunky, then no poor actor will be able to make it any better. You have to trust that your audience is generally way ahead of you. They’re smart and they know the language of film. They can guess who’s going to fall in love with whom and who works where and what they want. If you start telling them things they already figured out, they’ll start to hate you for treating them like idiots. The only people who tend to want more exposition are executives who think audiences aren’t smart. And so you’ll end up writing the reading draft, which is overwritten and explains a lot of things, and then the shooting draft, where you realize you don’t need all those longs speeches about how people are feeling and what they want out of life.

It’s all about being in a character’s head. I do like to sit in places by myself and eavesdrop on people’s conversations. I’m fascinated by people’s turns of phrase and their sometimes odd takes on the world. But I’m more interested in writing real characters with interesting personalities and then readjusting the dialogue once I’ve cast the actors who will play these roles. I’d rather use whatever odd energy they bring naturally, rather than dictate to them some quirky way of talking.

Jim Rash and Nat Faxon: Exposition probably gets thinned out as we revise and revise drafts. That first pass can feel like a “spit draft” just throwing out what needs to be accomplished in each scene even if that means the dialogue is crappy and filled with exposition or even “on the nose” statements about how that character is feeling right now.

Cody: I have to thank Austin Powers, because whenever that happens I’m just like, “Hey, here comes Basil Exposition!” and I laugh to myself. Sometimes you can’t help it. The studios like things to be super expository because they think you’re all dumb. I try to fight on behalf of the viewer. “They can figure out what’s happening. You don’t need all this.” I crack up every time I’m watching a movie and a character says, “Let me get this straight…” and then recaps everything!

Holofcener: I think I just understand the character. It comes easily to me. I just put myself in that character’s face and just start talking. Sometimes out loud to myself. I just picture that I’m them.

I guess sometimes I let myself be on the nose and then trim it, and realize that this doesn’t have to be told. I think I have an exposition meter at some point, and realize this doesn’t have to be told, this is really boring. And my scenes are generally very short.

Write Your Own Rules

Linklater: How to convey it all, the decisions that go into that, that’s the hard part. There are a lot of great stories; it’s hard to make a compelling movie. You can take the most colorful life of someone and you can make a very boring movie out of it if you don’t break convention, or everything’s the same and we’ve seen it all before, no matter how exciting. It’s the how to tell a story, the technical inspiration, the storytelling inspiration, what’s the form that story should take, what’s the best way for an audience to receive it.

Mark and Jay Duplass: The biggest rule to follow is this one simple question: “What do you want to see next?”

Holofcener: I have no rules. People who don’t like my movies would probably be like, “That’s right, she needs some.” I mean I think that having written as many screenplays as I have at this point in my life as I have, I feel it’s intuitive that I write something with conflict. When I was in college or whatever, I’d write two girls sitting around talking and thought it was so ingenious, and now I know better — to some degree — that there has to be some conflict, at least between the two people talking, or what they’re talking about.

I guess when I know I’m doing something that breaks the laws that I’ve created in my movie. For instance, in Please Give, there’s a couple of sequences where somebody disappears, I guess Catherine Keener is looking at a chair in the store, and we know that somebody has died in that chair, and she looks over and sees the dead person in the chair. And there’s no reason to believe that I’m about to do that in this movie, there’s nothing mystical that’s happened, or anything magical, and yet I thought, Fuck it, I want it, it works.

I shot that thinking, This is never gonna be in the movie, but I ended up liking it. So that’s breaking convention. Or having someone talk to the camera out of the blue, which I’ve never had or never did. Things like that. Or showing someone — if I’ve set up a story where it’s from a certain character’s point of view, and then suddenly we’re in a room without that character, that’s breaking convention. But I don’t care, as long as it works, that’s how I feel.

Wain: Most of the classic screenwriting rules are good to keep in mind, but I find that you have to go back and forth between looking at something through the lens of rules/conventions/structures on one hand, and freely imagining with no boundaries on the other. The rules I do go back to often are: In a comedy you need to have jokes on every page, unless you’re going for a very specific moment of breaking the form; every scene (and every beat) should have a good reason to be there or it should be cut.

Every rule is made to be (and has been successfully) broken. But I would say every script has to have a “reason to be” — a vague but helpful rudder that has kept me on track during long, frustrating projects.

Koppelman: If a scene doesn’t have either internal or external conflict, it had better be damned interesting.

Curtis: On Love Actually, I was really finished in love and thought I understood how to write romantic films.

Two of the films in that were two films I was thinking of writing, the Hugh Grant one and the Colin Firth one, and then I thought, I don’t want to write another whole romantic comedy, what about if you could do a sort of ecstatic film, where you just saw the best bits of 10 films, rather than just one whole film? And when I thought that, I thought, I don’t only want to do the sort of romantic kissing ones, and that’s when I put in the Laura Linney story and the Emma Thompson story and the Liam Neeson one, which starts with a funeral.

Weber and Neustadter: The only rule we have is that it can’t be boring. If you’re bored writing it, people will be doubly bored reading it. And it’s important to think about the reader. Who are the people reading your stuff? When it comes to screenplays, for the most part, it’s people whose job it is to read 10 a weekend and they have things they’d rather be doing. If you’re able to hook THEM, to keep them turning the page of YOUR script vs. another one in the stack, the battle’s half won.

We don’t want the audience ahead of the characters, we never want to be overly treacly, we avoid coincidences at every turn. But with conventions, we would say nothing is absolutely absolute. One thing we would never do is avoid convention because it’s a convention. If it’s lame, that’s one thing. But if two characters have to meet — and they probably, eventually do — that’s a convention you can’t avoid. The true goal should be to make sure your version of that convention is memorable and effective rather than to avoid it entirely.

Writing Yourself Out of a Corner

Feig: I’m very deliberate when I write my first draft. I won’t move forward if I can’t think of the right word or description of an action. And so I tend to see corners coming before I get too deep into them. By letting my characters show me the way, I sometimes like to let them lead me into what I fear might be a corner because then the fun is figuring out how they would actually get out of it. I think if you don’t lead yourself into what you fear might be a corner, you risk writing a story that is predictable or not terribly interesting.

My favorite thing in movies or television is when a character is heading into something and I’m thinking, Holy shit, how in the world are they going to get out of that situation? The problem is that oftentimes the solution isn’t good or is convenient or has a deus ex machina that makes you lose faith in the people who are telling the story. But when a storyteller leads you into an unsolvable situation and then gets you out of it in a way that you never saw coming and that totally makes sense, it’s viewer nirvana.

Cody: Just keep writing; you’ll get out. It’s like getting stuck in a bumper car. Turn the damn wheel and mash the pedal and eventually you’ll do a 180.

Curtis: For me, the most important scene in Four Weddings was the scene that I realized I fucked up the film. Because I’d written a lot of it and we had the funeral, and anyone who sees the funeral would know that true love is real, and can’t be found and they had experience of it, there is such a thing as the right person, that’s what the funeral says to every person in the movie. And then, structurally, I planned that we should cut straight to Hugh marrying the wrong person. And that made that character an idiot who was going in completely the wrong direction. And so I realized the film is fatally flawed, because every single person will know, and then you cut to your leading character who you’re meant to empathize with, who is the only person in the room who doesn’t know what happened.

I spent months on that one scene and finally found a way of getting him to the wrong position. The way I did it was having him have a conversation with the most lovely person in the film who was also not clever. He had a conversation with James Fleet’s character, and James said, “I never expected true love, I just thought I’d just bump into someone who didn’t find me revolting. It worked for my parents until the divorce.” And so you were sort of suckered into the wrong conclusion. But before I did that, I’d have a conversation with Andie, a conversation with Kristin [Scott Thomas], and had all of them talking about the whole issue; I tried every way to get to the end of the movie, and that’s one of those things where you realized that your thought is flawed and you have to use a lot of craft to get from A to B.

Rip It Up and Start Again

Gerwig: I’d never had an entire movie written and said, “You know what? The middle 40 pages actually need to go,” and thrown it all out. Stuff like that. It’s painful, but Noah [Baumbach] is so good at being ruthless that I learned how to be a little ruthless. It’s throwing stuff out and moving stuff around and just chopping.

Koppelman: Always be open to the idea that we should just cut a huge section, start again. Have done it many times. It’s brutal. But then kind of joyous because you are at the beginning again, with all that open road in front of you.

Bell: Once I have a draft down, that’s when I start to get pretty obsessive about hitting the right beats. But initially, I write without judgment, without adhering to any rules. My first draft is always very free, and the draft later, once I’ve written “the end,” then I start to be a little more hard on myself and start adhering to the satisfying beats in a film that you want to have, even if you derail a little bit.

Feig: I try to not fall in love with my writing. It’s the downfall of so many writers. There are two things I always have in my office. One is a model of the Titanic, to remind myself that no matter how great something seems, it can still sink and fall apart. And the other is a bust of Shakespeare, to remind myself that I’m not Shakespeare. All writers’ writing can always get better.

It’s the falling in love with the first thing that comes out of your head that is what will take you down. It will make you impossible to work with and it will result in things often not being as good as they could be. Sure, sometimes you nail something the first time, but even then, it’s worth taking a crack at making it better. As Judd Apatow told me when we were prepping the pilot for Freaks and Geeks, “Let’s have you try to make the script even better. If it’s not, your original script will still exist. We’re not going to burn every copy of it.”

Koppelman: The opening voiceover in Solitary Man is one of my favorite things I have ever written. Maybe because I finally got to use a line I’d been carrying around for years. It was something a friend’s father said to him when my friend was a teenager. “Son, find ‘em where you fuck ‘em, and leave ‘em where you find ‘em.” Hilarious and mean and great. And I think it helped to land Michael Douglas. Because it was so dark. But we cut it in editing. And in so doing, basically saved the movie. It took me months to realize it. Made the character too unlikable too soon. But I still love the hunk.

Rash and Faxon: There was a scene in The Way, Way Back that we ended up having to lose in the final edit. It was a scene where Duncan (Liam James) is riding back on his bike with Peter (River Alexander) after staying out all night at a party. This was a fun scene that we loved on paper and when we shot it, but it slowed down the story as we headed into the final moments of the film.

Cody: I don’t have a formal rewrite process; I just compulsively groom and regroom scenes like a cat with OCD… I’m still mentally rewriting Paradise and it’s been in the can for months.

Ask for Help — and Partner Up!

Faxon: A lot of our Groundlings [Los Angeles sketch and improv comedy theater] training relates over to what we do now, in terms of brainstorming and improvising and collaborating together. There are times when, usually at the end of the day or something, I’m tired and then Jim will, wanting to solve the problem, take it home with him and come in the next day with a beautifully crafted scene. But we don’t usually pass stuff back and forth. We don’t usually split up duties and say, “You take this 20 pages” or whatever. We do as much as we can together without killing each other — or without Jim killing me.

Feig: You’re only as good as the people around you. With comedy especially, when you start to die in comedy as you get older is when you go, “Don’t tell me! I know what I’m doing.” You cannot survive, because comedy is ever-changing. The wake-up call for me was, I directed a lot of The Office over the years and in the fifth season I went in as a co-exec producer, so I was in the writer’s room a lot. They have all these twenty- and thirtysomething writers who are hilarious, and some guys my age.

So you have the kind of joke areas that you like to pitch and you get laughs and I was pitching these out, and the twenties and thirties were looking at me like I was crazy. I realized, “Oh my god, I’m like a dad. I’m telling dad jokes.” So hearing them and hearing their joke pitches, I said, “Oh, I see, it’s the tone that’s going on now.” You say, “Oh, I get why that’s funny now,” and referentially you see what doesn’t work because it’s old or whatever. So you just need to then magnify that by a thousand and deputize everyone around you and make sure you’re working with younger people, with older people, and you just want a big consensus, and that way you’ll hit the whole audience basically.

Gerwig: The thing with writing is nobody cares if you don’t write. Unless you’re commissioned to write something, but nobody was like, “How’s that movie about that dancer going?” Or like, “I need those pages.” It helps to have a writing partner. Anyways, I felt like I’d gotten kind of sidetracked by acting and it was really just such a tremendous gift that Noah [Baumbach] asked if I wanted to do Frances Ha.

To start, I emailed him a list of different moments and snippets of scenes and maybe some characters. He added some things to the list and then we just started writing. Really, you just start letting the characters talk to each other and see what happens and we started just generating scenes. We’d say, “Write that scene and see what that scene is and email it to me, and I’ll write this scene and I’ll email it to you.” Then, we’d see what the story was that was emerging out of that. It took about a year.

It was a long process. It was hard too; I’d never really worked that intensely on a piece of writing. I’d written things in college, and then after college, plays, but I’d never really gotten further than two drafts in, and so I’d never learned how to take something apart and put it back together.

Feig: I really labor over my first drafts, so that they’re usually in pretty good shape. Then I’ll get feedback from a few trusted readers and make more adjustments based on their feedback. The notes I’m most interested in things people didn’t understand, things people found confusing, and things in my script people have seen before in movies that I haven’t seen.

I’m less interested in notes that begin with “What I would have done…” since everybody’s head works differently and what another person would have done with a character or an action is different from what my experiences led my characters to do. That’s not to say I don’t want to hear all notes. I think that most notes have a totally valid point buried in the middle of them. The problem is when people then try to present a solution for the problem. I just want to hear the problem and then go away and fix it in my own way.

But don’t be the person who argues against people’s notes. If you asked for their opinion, hear them out, write down their thoughts, and then compare their notes to everybody else’s. If you start to see a pattern on certain issues people are having, those are the things you definitely need to fix. Remember, just look at that bust of Shakespeare on your desk and get back to work.

Dealing with Interference

Cody: Nobody wants to make movies about unfuckable women, period. I always have to make everyone hotter. “She can be pregnant, but she has to be cute too.” “She can be a burn victim, but she has to be cute too.” “We can’t put glasses on Amanda Seyfried; she won’t look as hot.” It never fucking ends. My latest script is about a woman in her sixties, so that should be interesting. She’ll be a very fuckable 60, I’m sure.

Feig: It was a kid’s movie I did a big rewrite on that I was very happy with. I went into my first week of directing it and suddenly the studio head had a change of heart and made me pull out most of the dramatic underpinnings of the story, so that all I was left with was basically a silly romp. I was still able to salvage some of the heart but it gutted it enough that it was a letdown to most critics, as well as fans of Freaks and Geeks. That said, I’m still very proud of the movie. It’s just not what it could have and should have been.

There was a script I was writing under a blind script deal I had at a studio right after Freaks and Geeks was canceled. I had an idea I loved called Weirdo that was about a bunch of nerds in a small town who stage a UFO invasion to make people stop making fun of them. But my development executive was hung up on me coming up with a Don Quixote story. I’d go in with ideas I loved and then he’d change them all around to fit his Quixote fetish and I’d walk out completely confused about what I was supposed to write.

Wain: I listen to/read them carefully, and try to understand the underlying reason the note was made. Often the specific note is more of an indication of something else that’s wrong. Even if I totally disagree with a note, I try understand why it was given. That said, ALL notes should be filtered through the ultimate gut of the person who’s sitting in front of the keyboard putting the thing together.

Second-guessing the audience (or the studio/buyer/financier/producer) is a trap I try to steer clear of. The idea of “This isn’t making me laugh but it’s the kind of thing that will probably make them laugh” is a dangerous pitfall.