Dragon's Head Nebula

.jpg)

This nebula sometimes referred to as the Dragon's Head is part of the larger Seagull Nebula system. The Dragon's Head is composed of NGCs 2035, 2032 and 2029. It is an attractive area displaying some great blue reflection nebula which was brought out by some of Steve Mazlins processing on this data.

By: Harvey; Catalog: NGC 2035; Obj Type: Nebula;

Location: CTIO, Chile; Date Taken: December 31, 2008

Exposure Time: Ha (8Hrs) RGB (3 Hrs each); Camera: Apogee Alta U47

Telescope: RCOS Carbon Truss 16 inch f/11.3 Ritchey-Chretien

Mount: Software Bisque Paramount ME

© 2013 Harvey http://www.starshadows.com

Dragon's Head Nebula Is a Beauty, Not Beast, in Amazing Telescope Views

By Miriam Kramer, Staff Writer | November 27, 2013 07:00am ET

Stars in a little explored region of the Large Magellanic Cloud — one of the closest galaxies to the Milky Way — shine in an amazing new photo taken by a telescope in Chile.

Credit: ESO

The photo, released by the European Southern Observatory today (Nov. 27) and taken by the Very large Telescope, shows new, intensely hot stars molding their surrounding dust and gas into a nebula known as NGC 2035, or the Dragon's Head Nebula, about 160,000 light-years from Earth. You can watch a video fly through of the cosmic image provided by ESO.

While the baby stars are on prominent display, the left side of the image also reveals the remnants of a supernova — an explosion that marks the death of some stars, ESO officials wrote in a release.

The huge pink, purple and blue cloud of dust on the right side of the photo is an emission nebula. Young stars emit radiation, causing the gas surrounding them to glow, but lurking within that gas are dark spots that create the "weaving lanes and dark shapes across the nebula," ESO officials wrote in a release.

"From looking at this image, it may be difficult to grasp the sheer size of these clouds — they are several hundred light-years across," ESO officials said. "And they are not in our galaxy, but far beyond."

The Large Magellanic Cloud is about 10 times smaller than the Milky Way at about 14,000 light-years across, ESO officials added.

Supernova explosions can be brighter than their host galaxies for a short time, but fade over the course of weeks or months. Once a massive star runs out of fuel, it can explode as a supernova after collapsing in on its own gravity. Other supernovas are created as a star steals matter from a stellar neighbor until a nuclear reaction takes hold.

The European Southern Observatory is supported by 15 different countries including Brazil, Austria, Denmark, France Finland, Germany and the United Kingdom among others.

Baby Star

Herbig-Haro 46/47 is releasing two jets of materials at high speeds, causing gases around the young star to glow. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array captured this glow, revealing a more energetic star than previously thought.

Credit: ESO / ALMA

www.space.com

Credit: ESO/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/H. Arce. Acknowledgements: Bo Reipurth

This image of Herbig-Haro object HH 46/47 combines radio observations acquired with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) with much shorter wavelength visible light observations from ESO’s New Technology Telescope (NTT). The ALMA observations (orange and green, lower right) of the newborn star reveal a large energetic jet moving away from us, which in the visible is hidden by dust and gas. To the left (in pink and purple) the visible part of the jet is seen, streaming partly towards us.

Credit: ESO/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/H. Arce

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have obtained a vivid close-up view of material streaming away from a newborn star. By looking at the glow coming from carbon monoxide molecules in an object called Herbig-Haro 46/47 they have discovered that its jets are even more energetic than previously thought. In these observations from ALMA the colours shown represent the motions of the material: the blue parts at the left are a jet approaching the Earth (blueshifted) and the larger jet on the right is receding (redshifted).

Credit: ESO/Bo Reiburth

This image from ESO's New Technology Telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile shows the Herbig-Haro object HH 46/47 as jets emerging from a star-forming dark cloud. This object was the target of a study using ALMA during the Early Science phase.

Credit: Karl Tate, Space.com Infographics Artist

Made up of dozens of small radio telescope dishes, the ALMA telescope will be one of the most powerful in the world when finished.

Credit: ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgement: Davide De Martin

This wide-field view shows a rich region of dust clouds and star formation in the southern constellation of Vela. Close to the centre of the picture the jets of the Herbig-Haro object HH 46/47 can be seen emerging from a dark cloud in which infant stars are being born (to zoom in use the zoomable version of this image). This view was created from images forming part of the Digitized Sky Survey 2.

by SPACE.com Staff | August 20, 2013 10:01am ET

Hubble Images

The striking Sharpless 2-106 star-forming region is approximately 2,000 light-years from Earth and has a rather beautiful appearance. The dust and gas of the stellar nursery has created a nebula that looks like a ‘snow angel.’

NGC 3314 is actually two galaxies overlapping. They’re not colliding – as they are separated by tens of millions of light-years – but from our perspective, the pair appears to be in a weird cosmic dance.

To celebrate its 23rd year in space, the Hubble Space Telescope snapped this view of the famous Horsehead nebula in infrared light. Usually obscured by the thick clouds of dust and gas, baby stars can be seen cocooned inside this stellar nursery. For the last 23 years, Hubble has been looking deep into the Cosmos returning over a million observations of nebular such as this, but also planets, exoplanets, galaxies and clusters of galaxies. The mission is a testament to the the human spirit to want to explore and discover.

Light from an ancient galaxy 10 billion light-years away has been bent and magnified by the galaxy cluster RCS2 032727-132623. Without the help of this lensing effect, the distant galaxy would be extremely faint.

This is 30 Doradus, deep inside the Tarantula Nebula, located over 170,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. 30 Doradus is an intense star-forming region where millions of baby stars are birthed inside the thick clouds of dust and gas.

Arp 116 consists of a very odd galactic couple. M60 is the huge elliptical galaxy to the left and NGC 4647 is the small spiral galaxy to the right. M60 is famous for containing a gargantuan supermassive black hole in its core weighing in at 4.5 billion solar masses.

With help from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope in New Mexico, Hubble has observed the awesome power of the supermassive black hole in the core of elliptical galaxy Hercules A. Long jets of gas are being blasted deep into space as the active black hole churns away inside the galaxy’s nucleus.

NGC 922 is a spiral galaxy with a difference. Over 300 million years ago, a smaller galaxy (called 2MASXI J0224301-244443) careened through the center of its disk causing a galactic-scale smash-up, blasting out the other side. This massive disruption generated waves of gravitational energy, triggering pockets of new star formation – highlighted by the pink nebulae encircling the galaxy.

Four hundred years ago a star exploded as a type 1a supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) some 170,000 light-years from Earth. This is what was left behind. The beautiful ring-like structure of supernova remnant (SNR) 0509-67.5 is highlighted by Hubble and NASA’s Chandra X-ray space observatory observations. The X-ray data (blue/green hues) are caused by the shockwave of the supernova heating ambient gases.

The intricate wisps of thin gas (billions of times less dense than smoke in our atmosphere) from Herbig-Haro 110 are captured in this stunning Hubble observation. Herbig-Haro objects are young stars in the throes of adolescence, blasting jets of gas from their poles.

Contained within an area a fraction of the diameter of the moon, astronomers counted thousands of galaxies in the deepest observation ever made by Hubble. Combining 10 years of Hubble observations, the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF) has picked out galaxies that were forming when the Universe was a fraction of the age it is now.

Hubble's Latest Mind Blowing Cosmic Pictures

APR 19, 2013 01:00 PM ET // BY IAN O'NEILL

Internet free speech: We’re doing it wrong

Internet free speech: We’re doing it wrong

By Andrew Couts — August 7, 2013

When you ask the kind of geeks who sit around pondering the value of our connected digital world what makes the Internet so great, one answer always pops up: Openness and free speech. Just look at how much access we have to the world’s information, they say. Look at how free speech has thrived and spread throughout most of the globe. The Arab Spring! Occupy Wall Street! “Breaking Bad” episode recaps! And I agree, all those are great examples of the way the Internet has made life better for countless people. But there is a sad fact about our newfound ability to disseminate whatever we want, anytime we want: We just aren’t very good at it.

The most poignant recent example of this comes from the New Yorker’s Ariel Levy, who took a deep dive into the Web’s role in the case of Steubenville, Ohio, football players, two of whom were found guilty earlier this year of raping an intoxicated teenage girl from West Virginia.

Levy’s excellent reporting will undoubtedly evoke sickening outrage at those who were responsible for violating a young girl. But it does something else, too: It shows just what happens when we, the couched commentators of the Web, try to take matters into our own hands – often acting on bad information.

This excerpt from the long-read piece highlights the problem:

In trying to determine what happened in Steubenville, the police and the public began with the same information, gathered from the same online sources: ugly tweets, the Instagram photograph, and a deeply disturbing video. But while the police commandeered phones, interviewed witnesses, and collected physical evidence from the crime scene, readers online relied on collaborative deduction.

The story they produced felt archetypally right. The “hacktivists” of Anonymous were modern-day Peter Parkers—computer nerds who put on a costume and were transformed into superhero vigilantes. The girl from West Virginia stood in for every one of the world’s female victims: nameless, faceless, stripped of identity or agency. And there was a satisfying villain. Teen-age boys who play football in Steubenville—among many other places—are aggrandized and often do end up with a sense of thuggish entitlement.

In versions of the story that spread online, the girl was lured to the party and then drugged. While she was delirious, she was transported in the trunk of a car, and then a gang of football players raped her over and over again and urinated on her body while her peers watched, transfixed. The town, desperate to protect its young princes, contrived to cover up the crime. If not for Goddard’s intercession, the police would have happily let everyone go. None of that is true.That’s right – none of that is true. And yet, in the real-time frenzy of Twitter, Facebook, and blog comment sections, we have a culture in which the nitty-gritty truth does not matter, as long as the overall narrative of any given story is right. And from that flimsy platform, we spring forward with threatening or derogatory words directed at whomever we believe are the villains.

This blind beast of online fury reared its ugly head in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing. Reddit and Twitter users mistakenly identified Sunil Tripathi, a Boston-area college student who had been missing for a month, as one of the possible terrorists.

Law enforcement authorities quickly cleared Tripathi’s name. But, as The New York Times recently reported, it was not nearly quick enough to spare the Tripathi family from the wrath of the Web. Not long after the bombing, Sunli Tripathi’s body was pulled from a river.

Most recently, we saw our misuse of the Internet’s quick and dirty communication tools used to threaten the life of Dave Vonderhaar, design director of Call of Duty: Black Ops 2, over a minor game update that had little impact on the game.

These are just a few notable, high-profile examples of how our use of free speech online has become tainted by a desire to be part of events or conversations for which we have little value to add. Twitter and Facebook are littered with garbage comments and unjustified vitriol. Reddit is a cesspool of flash judgments about people or events, by users who think they know what’s right and what’s wrong better than anyone else.

None of this is to say people aren’t entitled to their opinion, or should keep their thoughts to themselves. Nor am I saying that the Web isn’t equally filled with good vibes and positivity – there is just as much of that as there is hateful ignorance and cruelty. But it seems as though the bad stuff has begun to float further towards the top.

What I am trying to say is that our collective online behavior in cases like Steubenville and Boston could eventually have negative effects on the amazing gift of broad free speech online.

First, the spewing of gut reactions to events degrades the value of our collective discourse to the point where what’s being said online contributes little to the overall conversation. If half of the tweets out there are filled with meanness and misinformation, we have taken a step backwards, not the other way around.

Second, our propensity to jump into real-life events with real-life consequences without a full comprehension of either, as exhibited during the Steubenville and Boston fiascos, could lead to less openness in the offline world. Police and government officials may be less willing to reveal information for fear of an online witch-hunt. And victims, like the victim from West Virginia, may be less willing to come forward about crimes committed against them due to the possibility that thousands of Web users will hound them with cruel messages or worse.

In short, as our use of the Web and social media continues to evolve, we must not lose sight of both the power that these tools have, and the possibility that our abuse of them could destroy what we love about them.

William Shatner, Reddit, And The Complications Of "Free Speech" On The Internet

Whitney Phillips and Kate Miltner | February 12th, 2013

Whitney: Two weeks ago, William Shatner tweeted with Chris Hadfield, an astronaut stationed at the International Space Station. This resulted in the ENTIRE INTERNET BEING WON by Shatner, at least according to this Reddit thread. Apparently the 81-year-old Shatner got wind of the thread, and promptly created an account. He then proceeded to spend the next few days feeling out the platform and openly criticizing its most characteristic elements, namely Reddit's karma system, wherein points are given or deducted based on community feedback, as well as AMA threads, which stands for "Ask Me Anything" and provides celebrities and other notables an opportunity to interact with fans. Regarding the karma system, Shatner expressed outright confusion ("isn't the system basically broken?" he asked), and regarding AMAs, Shatner wondered if it was meaningful for anyone but the people who happened to be sitting in front of the computer as the conversation unfolded. And anyway, he asked, "don't I do that daily on Twitter?"

Shatner then tackled a much meatier problem—Reddit's moderation policies. Or lack thereof, as he lamented, which are inextricably tied to the aforementioned karma system, in which "good" comments are rewarded with karma points and increased visibility while the "bad" comments are downvoted and essentially run out of town. Shatner was appalled by what often passes as "good" commentary on Reddit ("good," here, translating to "most popular/most upvoted," not necessarily "positive"), namely rampant racism, sexism and homophobia. "The fact that someone could come here, debase and degrade people based on race, religion, ethnicity or sexual preference because they 'have a right' to do so without worry of any kind of moderation is sending the wrong message, in my humble opinion," he wrote.

Kate: I guess this whole thing just proves that William Shatner is a Rocket Man, burning up his fuse out there, alone. WILL-IAM! SHAT-NER!

(Sorry.)

Seriously though, good for Shatner. From the comments that followed, he said what a lot of people have been saying or wanted to say, which is that this sort of noxious speech and content is not acceptable, and that it shouldn't be tolerated by the moderators.

Whitney: My interest in Shatner's comments are twofold. The first is good old fashioned Schadenfreude, because how do you like that nerd apple, Reddit (a breakdown of my feelings about the site can be found here). The second reaction was much more reflective, since Shatner's argument—which takes for granted that Reddit as a whole (meaning all its mods and admins) are responsible for, as they say, the shit Reddit says—dredges up a number of larger questions, particularly the ideal relationship between platform user(s) and platform moderator(s). What is the ideal relationship? Do users have a "right" to "free speech" on privately owned platforms, as many Redditors insist between rape jokes? Do platforms have a responsibility to shut that sort of content down before it ingrains itself in the site culture?

Kate: Ah, responsibility. What a loaded word! Okay, so first of all, if we're going to talk about the site culture, we need to look at its roots. Reddit is a platform that is largely based in the libertarian ethos of the early web. Free Speech At All Costs is a fundamental precept of that ethos, and for better or worse, I think that's what's fueling a lot of these claims of FREE SPEECH!!11. Just to provide a little bit of context: in 1996, John Perry Barlow (one of the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation) wrote A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. In it, he declared:

We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity… In our world, all the sentiments and expressions of humanity, from the debasing to the angelic, are parts of a seamless whole, the global conversation of bits. We cannot separate the air that chokes from the air upon which wings beat.

So, if you come at it from this perspective, you cannot separate "good" speech from "bad" speech, and as such, both are protected (or should be).

The thing is, as much as some Redditors may want to claim otherwise, Reddit is not The Internet. Reddit is a privately owned platform that can decide what sort of user-generated content will or will not be tolerated. Legally, Condé Nast (who owns Reddit) can do whatever they want to control what is posted on the site (which seems like not much, because pageviews, probably). The question that Shatner's comments raise is whether or not they should.

Whitney: And yet the "free speech" issue lingers (scare quotes used to differentiate the legal sense of the term from the cartoon internet sense of the term), which is best summarized by the concurrent assertions that "you are not the boss of me" and "don't tell me what to do." This card is most frequently played by those who think they should be able to do or say whatever they want whenever they want, often at the expense of women, gays and lesbians, and people of color, because… well because free speech (I'm looking at you, Men's Rights-types). In response to Shatner's posts, many Redditors either directly reiterated this position, or argued a slightly more nuanced version of the same thing, namely that imposing some external morality police (for example by assigning paid moderators to each specific subreddit) would undermine the very spirit of the site, which is based on, you guessed it, "free speech."

To be fair, as several Reddit users pointed out, Reddit is already subject to some on-site moderation. Reddit is a self-moderating community; community members police their own borders through upvoting (which, again, is designed to reward the good and punish the bad, at least what passes as "good" and "bad" on that particular subreddit). Furthermore, volunteer moderators, who are also members of the community, can intervene when other users cross whatever behavioral or ethical line deemed acceptable/desirable by the subreddit (which is often determined through karmic upvoting/downvoting—what the community accepts is the content the community consistently upvotes). In other words, Reddit is designed to self-regulate; so long as individual subreddits are allowed to decide what's appropriate for themselves, we should be good.

Kate: Right, but what subreddits often decide is "appropriate" is the type of content that a lot of other people find offensive, and Reddit's boundaries are porous—the site is set up for community-sourced discovery. We talked about this issue of competing norms and mores last time around with our public shaming discussion; what some people find acceptable (or entertaining) can be completely offensive to others. Taste and opinion aside, you're also dealing with a medium where it's relatively easy to misinterpret context, or intent, or any number of things that give content meaning within a particular community.

As redditor Morbert said in the comments, "Reddit isn't a single community. It is a variety of communities, for better or for worse." That makes things incredibly tricky. The truth is, there are some racist, homophobic, misogynist jerks out there who think that there is nothing funnier than a rape joke (ugh). These people are going to congregate somewhere—and I hate to say it, but that is their right—and I mean that in a constitutional sense: it is totally the legal right of gross bigots to hang out on a message board and make disgusting jokes about anyone who is not white and male, because that is what our laws allow.

The other thing I wanted to bring up is why we are even talking about this in the first place. I mean, who cares whether or not Reddit is tolerant of this sort of stuff except for people who hang out on Reddit? Why is this even a story to begin with? Well, it's a story because Reddit is an influential platform—influential enough that President Obama's campaign staff thought it would behoove him to do an AMA. So the reason that this matters is because one of the most influential and highly-trafficked sites on the internet is also a site that hosts a lot of content that demeans and insults the majority of the US population.

Whitney: That Reddit has been plagued with, let's call them, "behavioral issues" isn't just surprising, it's built into the platform, which is then built into the overall ethos of the site. This is not to say that all Reddit users are Violentacrez clones, or that all subreddits are gross—many users are extremely thoughtful (you can see that in one of Shatner's follow-up threads; scroll down to see a handful of Redditors grappling with many of these same issues). Take these comments, for example:

From Redditor oxynirate:

As a girl on reddit I get really upset and disheartened about the amount of sexist bull I see on here. It's not just sexist crap, it's down right hypocritical. One day you'll see an article on the front page about men protesting rape, and the comments will be all about how they would never commit a rape and are super anti rape. Until someone goes in there and posts about their being raped. They get called liars, told they put themselves in that situation and so on. I had one guy tell me I wasn't raped because I gave up protesting, fighting back and saying no. He said persistence doesn't equal rape.

And from BottleRocket2012 (in response to the claim that Reddit isn't a single community, and that for better or worse it is comprised of many smaller communities):

I think this is the frequent reddit response. But the reality is all the racist "humor" that makes the front page is upvoted by the community at large and these millions of people aren't rotated every day. The other reality is everyone reading William Shatner's posts thinks he is talking about other people. I mean "OP is a faggot" is a hilarious meme and he isn't getting the inside joke. And besides a gay person said "I'm gay and I find this hilarious" so now in the mind of a redditor this isn't hating. No racist ever thinks they are, everyone creates a wall of bullshit to believe what he is doing is ok.

And smaller subreddits—a subreddit devoted to the staggering variety of topics covered by other subreddits can be found here—are much less likely to be overrun by violent sexism (except for subreddits devoted to violent sexism, oh for example /r/beatingwomen, which has nearly 34K subscribers).

That said, the site as a whole is undergirded by a basic kind of libertarian permissiveness. In a perfect world, one that has achieved gender, racial and sexual equality, and in which all voices are equally represented, this sort of permissiveness might be enough to ensure a stable, healthy, self-regulating platform. But this is not a perfect world; you can't hand a bunch of racists, misogynists and homophobes the keys to the castle and then reasonably expect them to deny entry to other racists, misogynists and homophobes (for a visual representation of this idea, consider the following infographicfrom Modern Primate). So what to do? The obvious answer is to take away the keys and hand them to someone who doesn't stand to benefit from all that permissiveness. Someone who couldn't give two shits about the karma they stand to win or lose. In other words, you start moderating. And not just moderating, but culling the very worst offenders. Extreme, maybe, but so is /r/beatingwomen. (And yes, I am fully aware of the practical complications of iron-clad moderation policies, namely that lots of moderation requires lots of paid employee labor, and furthermore that said labor is often actively thwarted by those with mayhem in their hearts. I am also aware that ban-happiness flirts with a whole new set of problems, usually having to do with the mod's personal bias. Still, I present to the jury the basic failings of Reddit's current moderation model, and suggest that what they're doing now doesn't work, and merely opens the door for all kinds of abuse.

Kate: Yes, ugh. God. And /r/rapingwomen and /r/killingwomen. Technically, all of those fit the definition of hate speech, which means that they go from offensive to (borderline? technically?) illegal, which is another issue, really. The majority of racist and sexist content/commentary on Reddit—the commentary that Shatner was referencing— isn't that extreme (thank god). And this is where I get squirmy about culling—because it's all so relative and context-dependent ("I said 'OP is a faggot' sarcastically to point out its innate homophobia and call everyone else out on their bigotry, look at my previous trail of comments"). I've already said this elsewhere but: who moderates whom is a major issue. Who gets to decide what is acceptable and what is offensive? That is such a slippery slope—you cull (or dare I say censor) one thing, and then where does it stop? The path to hell is laid with good intentions, etc, etc.

The other thing is that having this stuff out in the open might not entirely be a bad thing, as upsetting as it might be (just stick with me for a second). There are a growing number of people out there who think that we're in a post-racial, post-gender, post-whatever world, and that racism and sexism aren't as problematic as they used to be (AHAHAHA, HA HA HA HA). The more that blatantly prejudicial/bigoted/hateful expression is pushed to the margins, the easier it will be for certain people to be like, "What do you mean, racism and sexism are problems? Oh, THOSE crackpots on weird site no one has heard of? Whatever, they're just a minority. CHECK MAH SOCIAL PROGRESS." I'd like to point out that you and I wouldn't be talking about this right now if these comments were being published on I'mARacist.com– we are only talking about it because it's on Reddit.

As you've noted previously, shaming (or in this context, moderating) ignorant people isn't going to change their fundamental beliefs. They'll just end up taking their isht elsewhere—and that may clean up the tone/content on Reddit/create a filter bubble for offensive content on major platforms, but it won't eliminate the underlying problem. It is absolutely essential that we (as a society, as individuals, as academics, as people who publish their opinions on websites) keep talking about this, frequently and publicly. Otherwise, these beliefs (which are not going away anytime soon) will become (further) silently institutionalized, which is arguably more difficult to combat.

Whitney: Yes, if you give a mouse a cookie, he'll want you to ban the word Christmas from all public-school functions (it's actually not a bad idea). The problem I've always had with that argument—if we start censoring some of the things, what will stop us from censoring ALL of the things??—is that it essentially plays on a person's fear of being silenced, not their sense of basic human decency. In short: this person is being censored for their beliefs. You don't want to be censored for YOUR beliefs, do you?? Then you better defend with your life other Redditors' right (which isn't actually their right, as they're posting to a privately owned website) to post incendiary, unnecessary, completely unproductive bile all day, because "free speech."

In other words, the argument that selective censorship can only lead us down a path to fascism often does little more than to lull everyone else into complicity, and therefore functions as preemptive self-censorship. You are encouraged to hold your tongue when you see something upsetting, because maybe next time you'll be the one whose speech is under the microscope. This is a problem, because some people need to be told to SHUT UP, particularly when their speech interferes with their audience's basic human right—what should be a basic human right—not to be constantly inundated with violently racist, sexist, homophobic, pedophilic or otherwise ignorant bullshit every time they go online. On Reddit, there are ways of shutting the most egregious content down; but in order for that to happen, some people (ahem, white dudes) have to be willing to acknowledge that the "free speech" to which they so desperately cling actually costs quite a bit, a point with which Reddit's managers and investors would also have to make peace. Because banning bigots would mean less traffic, and less traffic would mean less money. And wouldn't that be a shame. Which is not—I repeat, is not—an argument against offensiveness generally. Nor is it an argument against all forms of dissent or discomfort, both of which can be quite generative. This is an argument against what is already dead cultural weight. Nobody benefits from keeping it around, except maybe the websites themselves. But even then, it's not so much "benefit" as "profit."

Kate: I'm not arguing against solid moderation policies on Reddit or anywhere else. Those are private sites that can dictate the tone of discourse however they see fit. However, if we're talking about people shutting their mouths in the larger sense, I don't know if I agree. Speech—and who is listened to—is often about power and access. If restrictions on speech are put in place—even with the aim of helping marginalized groups—I worry that they will end up backfiring. Those who are used to having power are awfully good at figuring out ways to circumvent things to ensure it's business as usual.

A few months ago, social media scholar danah boyd wrote an excellent blog post about the nature of freedom of expression in a cross-national, online context. She was discussing the uproar over The Innocence of Muslims and the racist MTA campaign by the American Freedom Defense Initiative. Different case studies, same issues. She wrapped up the whole problem pretty neatly, so I'm just going to end it with a quote from her:

I think that we need to start having a serious conversation about what freedom of speech means in a networked world where jurisdictions blur, norms collide, and contexts collapse. This isn't going to be worked out by enacting global laws nor is it going to be easily solved through technology. This is, above all else, a social issue that has scaled to new levels, creating serious socio-cultural governance questions. How do we understand the boundaries and freedoms of expression in a networked world?

How, indeed.

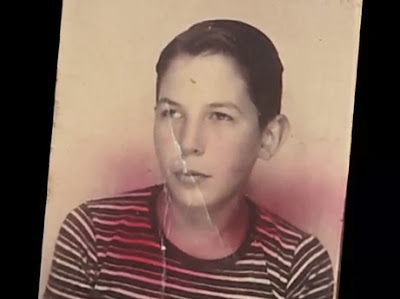

Leonard Nimoy

An Interview With Photographer Leonard Nimoy

by Jason Landry

Posted: 11/23/2013 6:45 pm

Jason Landry: Where does Leonard Nimoy the photographer go for inspiration?

Leonard Nimoy: It pops up. I don't go to any particular place looking for it. It has to arrive. It's the kind of thing that has to touch something in me when I read or see or hear something that's relevant.

It's unpredictable, as it should be. I try not to force an issue because then the work feels forced, too intellectual, and not spontaneous -- not out of the subconscious or the unconscious. I'm working very hard at trying to be in touch with the creative process rather than the intellectual process.

JL: From what I have read, you started making photographs as a teenager and built a darkroom in the family bathroom. At what were you pointing your lens back then?

LN: Family members, mostly. I still have a photograph that I did of my grandfather on the banks of the Charles River. I shot it with a camera that I still have, a bellows camera called a Kodak Autographic. It was one of these things that used to flop open when you pull the bellows out on to the track. These cameras were made with a little lid on the backside that you could open and inscribe something on the back of the film as a kind of a memory of what the photograph was. I never used the autographic feature, but I did use that camera to take pictures with, then I built an enlarger using that camera as the heart of it. I found a suggestion for that idea in a Mechanix Illustrated magazine: how to build your own enlarger using a metal lunchbox. For the light housing, I used one of those lunchboxes that had a dome-shaped top and I put a sock in there and a seventy-five-watt light bulb and cut a hole into the bottom of the lunchbox, mounted it onto a make-shift wooden frame, mounted the camera onto that, and then used a couple pieces of glass for the negative holder. I was able to take a photograph with that camera and then enlarge it with that camera.

JL: Going back to Robert Heinecken, was there anything specific that he taught you or might have said to you that left a lasting impression?

LN: Yes. As I mentioned, he was very strong on "theme," and if you wanted to be a photographic artist, you should not be just shooting pictures willy-nilly, and at anything you just happened to see or come across, but stick to his or her thematic thrust. And as an example, he said if you are walking down the street with your camera, and you see a person falling out of a high building, you don't shoot a picture of that falling person unless the theme of the work that you're working on has to do with the affect of space on the human figure. If you simply shoot it because it was happening, you have moved to photojournalism.

JL: "There's poetry in black and white." You said that in an interview once when describing black and white photography. Is the use of black and white a nostalgic thing, or a way that photographs should be displayed based on the subject matter?

LN: It has to do with nostalgia and subject. I grew up doing my own printing. Always enjoyed it, always enjoyed going into the darkroom and experimenting with a print. I did not move into developing or processing color. I stayed with black and white. I still think to this day that I prefer to work in black and white if it has to do with poetry or anything other than specific reality. I have worked in color when I thought it was the appropriate way to express the thought that I was working on. My Secret Selves project had to be in color. It was so specific to the individual and what they were bringing to the portrait session. Color is more specific and black and white is more poetic.

JL: For many years you were on the other side of the lens. How does it feel to be behind the lens directing your subjects through photography?

LN: It's liberating for me. I don't have to perform -- don't have to take on other identities. It's using a different part of my creative process, which I enjoy. It's refreshing.

JL: What is the most important lesson that you've learned through photographing people?

LN: How to make a subject or model comfortable in front of my camera. The other is that people come in all shapes and sizes in their psyche, and not just in the physical and metaphysical sense, but in their psychological condition. And it's a search -- you are searching constantly to find out who this person is. What is it that you want to extract from this person? There was this wonderful video of Richard Avedon taking a portrait of an actor, and he said to his subject (paraphrasing), "think of nothing...just let your mind go totally blank." And he takes the picture. And then I asked myself, what is Avedon looking to show here? Is he thinking that by telling this person to think of nothing that something wonderful or something special is going to emerge? Thinking of nothing could also make for a very dull picture. It could also create a blank canvas for people to project into. Every photographer has to find their own way into this territory. It's a life-long search. I don't think anyone every perfects it and is done with it. It's a work of art and it's never complete.

JL: If you were advising a young photographer today, what would your words of wisdom be?

LN: Stop worrying about the nature, design or qualifications of your equipment. Master your equipment so you know how to get the shot you want, but above all, search for the reason to be taking pictures. Why are you taking pictures? Why do we shoot pictures? I say the same thing to actors who want to develop a career as an actor. You must master your craft and then put it aside and concentrate on the more difficult aspect of the work. What is it that you want to do with that craft? What do you want to express? What do you want to explore? What do you want to find out? What do you want to present to people? Those are the issues that you have to search for.

The War Within: Treating PTSD

This week on 60 Minutes, Scott Pelley showed viewers an extraordinary look at cutting-edge therapies for veterans with PTSD. These new therapies are now being offered at VA hospitals across the country.

For a state-by-state directory of PTSD treatment programs at VA hospitals,

click on this link: http://www.va.gov/directory/guide/ptsd_flsh.asp and enter your address OR click on your state inside the map to find a facility near you.

click on this link: http://www.va.gov/directory/guide/ptsd_flsh.asp and enter your address OR click on your state inside the map to find a facility near you.

To find a therapist outside the VA system, click on this link: http://www.abct.org/ and fill in your city, state, and zip code, check the box that says Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and scroll down to the SEARCH box and hit enter.

To find further information about PTSD, treatments, and other resources go to the National Center for PTSD: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/

If you are in crisis and need immediate help, go to this link www.veteranscrisisline.net

and call 1-800-273-8255 and press 1.

© 2013 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

GRB 130472A

An unusually bright gamma-ray burst produced a jet

that emerged at nearly the speed of light.

Credit: NASA/Swift/Cruz deWilde

that emerged at nearly the speed of light.

Credit: NASA/Swift/Cruz deWilde

Stanford physicists played a key role in monitoring and analyzing the brightest gamma ray burst ever measured, and suggest that its never-before-seen features could call for a rewrite of current theories.

In April 2013, an incredibly bright flash of light burst from the direction of the constellation Leo. Originating billions of light-years away, this explosion of light, called a gamma-ray burst, has now been confirmed as the brightest gamma-ray burst ever observed. Astronomers around the world were able to view the blast in great detail and observe several aspects of the event for the first time ever, according to a press release issued today from Stanford University.

These astronomers said the data could lead to a rewrite of standard theories of how gamma-ray bursts work.

When the core of a massive star collapses, it can eject a jet of gas into space at nearly the speed of light. Collisions between the fast-moving gas and its surroundings, as well as within the jet itself, create gamma rays.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The April 2013 blast, named GRB 130472A, was observed by several space- and ground-based telescopes, and the data were analyzed by dozens of astronomers around the world. The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was the first to detect the event, and it quickly began monitoring the flood of radiation using its Large Area Telescope (LAT), whose principal investigator is Peter Michelson, a physics professor at Stanford and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Michelson leads the international collaboration that built and operates the LAT.

Fermi’s quick action, allowing the LAT to record nearly the entire event, yielded data that revealed previously unknown aspects of the mechanisms involved in a gamma-ray burst.

The findings are reported in a series of papers published by the journal Science at the Science Express website on November 21, 2013.

A special cosmic event

Several features of GRB 130472A combined to make it of particular interest to astronomers.

First, according to these astronomers, the blast occurred 3.6 billion light-years away from Earth, which is less than half the distance of the typical GRB. The record-setting 20 hours that the LAT observed gamma rays was longer than any other observed GRB. And, in addition to being the brightest GRB ever witnessed, it was also one of the most energetic. Nicola Omodei, a research associate at Stanford’s Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory who led LAT data analysis for one of the Science papers, said:

When that happens, we start seeing features that we were not able to observe before. Especially because it was very bright, you can uncover features that were not predicted by the standard models.

The leading theory explaining long gamma-ray bursts such as GRB 130427A posits that they are created during the most energetic explosions in the cosmos, which occur when a very massive star collapses on itself.

These explosions erupt a jet of elementary particles traveling at close to the speed of light. Within the jet, pressure, temperature and density are not uniform, creating internal shock waves that move inward and outward as faster regions within the jet collide with slower ones.

As the jet travels outward, it collides with the interstellar medium to create additional shock waves, called external shocks. Although details are not well understood, particles are accelerated at the shock front and, at the same time, interact with the surrounding electromagnetic fields. This causes particles to lose part of their energy emitting photons, through a process known as synchrotron radiation.

The balance between the gain in energy from acceleration by the shock and the loss of energy due to synchrotron radiation dictates the maximum energy of the photons that can be emitted by such a system. The highest energy photons among these are classified as gamma rays and are detected by the LAT.

The observations of GRB 130472A, however, didn’t quite match energy levels predicted by these models.

Close-up image of the brightest gamma-ray burst ever seen, taken in April 2013 by the ultraviolet/optical telescope on NASA's Swift satellite.

Credit: NASA/Swift satellite

An unexpected observation

For instance, the telescopes detected more photons, and more high-energy gamma rays, than theoretical models would predict for a burst of this magnitude. In particular, a few of these high-energy events are so energetic that they cannot be produced via existing models of synchrotron radiation from shock-accelerated particles.

Additionally, the prevailing thought was that the brightest flashes were driven by the explosion’s internal shock waves, but the evidence indicates that these photons were created externally. Omodei said:

It’s like having a blanket that’s too short. You pull it up to your chin and uncover your toes. With our standard model, if you try to explain the pulse, you will fail to explain the energy.

The new observations don’t rule out the existing model, but researchers will need to either amend portions of it or adopt a new theory altogether to account for these characteristics, said Giacomo Vianello, a postdoctoral scholar in Michelson’s group and a co-author who performed LAT data analysis and interpretation on three of the Science papers.

The microphysics of how particles are accelerated involves a certain amount of well-thought assumptions, and these assumptions therefore get built into the theoretical models used to predict the behavior of cosmic events. The assumptions are necessary in part because these events cannot be recreated in laboratory settings, he said, which highlights the critical role that observations play in the fine-tuning of fundamental physics theories. He said:

The really cool thing about this GRB is that because the exploding matter was traveling at [nearly] the speed of light, we were able to observe relativistic shocks. We cannot make a relativistic shock in the lab, so we really don’t know what happens in it, and this is one of the main unknown assumptions in the model. These observations challenge the models and can lead us to a better understanding of physics.

A gamma-ray burst that exploded in April 2013 is the most luminous object in the field, as seen in this image from NASA's Swift satellite. All the other objects seen in the image are stars from our own galaxy, while the gamma-ray burst is millions of times farther away. This section shows an area of the sky about a quarter the size of the full moon.

Credit: NASA/Swift satellite

Invisibility Cloaks

By Sebastian Anthony on August 14, 2013 at 11:16 am

Researchers at Northwestern University have designed an invisibility cloak that can temporally hide objects for an indefinite period of time. Objects covered by this invisibility cloak wouldn’t disappear from sight, but rather it would appear that time has completely stopped for the cloaked object. A clock, for example, would continue to tick — but to the human observer, the hands would never move. One use for such a cloaking device is security, where a thief might set up a temporal cloak in front of an object that he intends to steal — so that to any outside observers or security cameras, the theft — the event, in physics terminology — hasn’t yet occurred. There are, of course, lots of military uses as well.

The best bit, though, is that the Northwestern invisibility cloak is fashioned out of plain old mirrors, which means that the device should cloak the entire visible light spectrum. Most of the recent research into invisibility cloaks (both spatial and temporal) has focused on the use of metamaterials — man-made materials that can bend light in weird and wonderful ways. So far, though, we have only been able to engineer metamaterials that operate in narrow electromagnetic bands, such as infrared light or microwaves — which isn’t very useful if you’re trying to hide something from humans.

The process is somewhat complex, but by changing the reflectivity of the four electrically switched mirrors, events that occur at the object (O) can be hidden from the observer. The duration of the temporal cloak is twice the time it takes light to travel between A and B — and so if you place B a very, very long way away — such as on another planet — you could theoretically cloak an object for minutes, or hours… or light years. I guess you could even do it here on Earth, if you created a massive (and I mean millions of miles massive) network of mirrors capable of bouncing light around for a few seconds or minutes.

For now, it sounds like Lerma hasn’t yet built the device — but there’s no reason his design couldn’t be implemented today, using existing and readily available materials. In fact, given the time machine nature of this device, it’s possible that someone — perhaps the military — has already built it. We just can’t see it yet…

New invisibility cloak combines metamaterials and fancy electronics to be thinner, lighter, more invisible

By Sebastian Anthony on November 11, 2013 at 12:00 pm

A researcher at the University of Texas at Austin has devised an invisibility cloak that could work over a broad range of frequencies, including visible light and microwaves. This is a significant upgrade from current invisibility cloaks that only cloak a very specific frequency — say, a few hertz in the microwave band — and, more importantly, actually make cloaked objects more visible to other frequencies. The UT Austin cloak would achieve this goal by being active and electrically powered, rather than dumb and passive like existing invisibility cloaks.

As you probably know, the last few years have seen a lot of research into invisibility cloaks. These cloaks are mostly based on metamaterials — special, man-made materials that bend radiation in ways that shouldn’t technically be possible, allowing for cloaking devices that bend radiation around an object, hiding it from view. (Check out our featured story, The wonderful world of wonder materials.) The problem with these cloaks is that metamaterials are tuned to a very specific frequency — so, while that specific frequency (say, a thin band of microwaves) passes around the object, every other frequency scatters off the cloak. In a beautiful twist of irony, most invisibility cloaks actually create more scattered light, making the cloaked object stand out more than if it was just standing there uncloaked.

According to Andrea Alù at UT Austin, this is a fundamental issue of passive invisibility cloaks, and the only way to get around it is to use cloaks fashioned out of active, electrically active materials. It might change in the future with more advanced passive metamaterials, but for now active designs are the way forward. Research into active invisibility cloaks is currently being carried out by multiple groups, but none have yet been built.

Alù’s proposed design consists of a conventional metamaterial base, but with CMOS negative impedance converters (NICs) placed at the corner of each metamaterial square (top image). A NIC is an interesting electronic component that adds negative resistance to a circuit, injecting energy rather than consuming it. NICs are not widely used as we’re not entirely sure how to use them. Alù seems to propose that by interspersing NICs (which must be powered) with the metamaterial, multiple frequencies can be cloaked. In the image above, you can see a standard metamaterial cloak (blue), vs Alù’s metamaterial-and-NIC cloak (green). Alù’s proposed cloak is invisible over a large range of frequencies, while a standard passive cloak is only invisible for a small range, and more visible than non-cloaked devices in other ranges.

From our own experience with writing about invisibility cloaks on ExtremeTech, we’d have to agree that active designs make more sense. Where passive cloaks have all been incredibly bulky and not all that effective, an active cloak can be thinner, more flexible, and capable of cloaking a much wider range of frequencies. Given our mastery of CMOS, and the utterly insane things that we can do with computer chips, it seems foolhardy to not pursue active, electronic invisibility cloaks.

In hindsight, maybe this is the approach that the Canadian camouflage kook is using to achieve his Quantum Stealth tech. But I doubt it somehow.

Stanford engineers' new metamaterial doubles up on invisibility

The new material's artificial "atoms" are designed to work with a broad range of light frequencies. With adjustments, the researchers believe it could lead to perfect microscope lenses or invisibility cloaks.

BY BJORN CAREY

Stanford Report, May 6, 2013

All natural materials have a positive index of refraction – the degree to which they refract light. The nanoscale artificial "atoms" that constitute the metamaterial prism shown here, however, were designed to exhibit a negative index of refraction, and skew the light to the left. Technology that manipulates light in such unnatural ways could one day lead to invisibility cloaks.

One of the exciting possibilities of metamaterials – engineered materials that exhibit properties not found in the natural world – is the potential to control light in ways never before possible. The novel optical properties of such materials could lead to a "perfect lens" that allows direct observation of an individual protein in a light microscope or, conversely, invisibility cloaks that completely hide objects from sight.

Although metamaterials have revolutionized optics in the past decade, their performance so far has been inhibited by their inability to function over broad bandwidths of light. Designing a metamaterial that works across the entire visible spectrum remains a considerable challenge.

Now, Stanford engineers have taken an important step toward this future, by designing a broadband metamaterial that more than doubles the range of wavelengths of light that can be manipulated.

The new material can exhibit a refractive index – the degree to which a material skews light's path – well below anything found in nature.

"The library of refractive indexes that nature gives us is limited," said Jennifer Dionne, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering and an affiliate member of the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. "All natural materials have a positive refractive index."

For example, air at standard conditions has the lowest refractive index in nature, hovering just a tick above 1. The refractive index of water is 1.33. That of diamond is about 2.4. The higher a material's refractive index, the more it distorts light from its original path.

Really interesting physical phenomena can occur, however, if the refractive index is near-zero or negative.

Picture a drinking straw leaning in a glass of water. If the water's refractive index were negative, the straw would appear inverted – a straw leaning left to right above the water would appear to slant right to left below the water line.

In order for invisibility cloak technology to obscure an object or for a perfect lens to inhibit refraction, the material must be able to precisely control the path of light in a similar manner. Metamaterials offer this potential.

Unlike a natural material whose optical properties depend on the chemistry of the constituent atoms, a metamaterial derives its optical properties from the geometry of its nanoscale unit cells, or "artificial atoms." By altering the geometry of these unit cells, one can tune the refractive index of the metamaterial to positive, near-zero or negative values.

One hitch is that any such material needs to interact with both the electric and magnetic fields of light. Most natural materials are blind to the magnetic field of light at visible and infrared wavelengths. Previous metamaterial efforts have created artificial atoms composed of two constituents – one that interacts with the electric field, and one for the magnetic. A drawback to this combination approach is that the individual constituents interact with different colors of light, and it is typically difficult to make them overlap over a broad range of wavelengths.

As detailed in the cover story of the current issue of Advanced Optical Materials, Dionne's group – which included graduate students Hadiseh Alaeian and Ashwin Atre, and postdoctoral fellow Aitzol Garcia – set about designing a single metamaterial "atom" with characteristics that would allow it to efficiently interact with both the electric and magnetic components of light.

The group arrived at the new shape using complex mathematics known as transformation optics. They began with a two-dimensional, planar structure that had the desired optical properties, but was infinitely extended (and so would not be a good "atom" for a metamaterial).

Then, much like a cartographer transforms a sphere into a flat plane when creating a map, the group "folded" the two-dimensional infinite structure into a three-dimensional nanoscale object, preserving the original optical properties.

The transformed object is shaped like a crescent moon, narrow at the tips and thick in the center; the metamaterial consists of these nanocrescent "atoms" arranged in a periodic array. As currently designed, the metamaterial exhibits a negative refractive index over a wavelength range of roughly 250 nanometers in multiple regions of the visible and near-infrared spectrum. The researchers said that a few tweaks to its structure would make this metamaterial useful across the entire visible spectrum.

"We could tune the geometry of the crescent, or shrink the atom's size, so that the metamaterial would cover the full visible light range, from 400 to 700 nanometers," Atre said.

That composite material probably won't resemble an invisibility cloak like Harry Potter's anytime soon; while it could be flexible, manufacturing the metamaterial over extremely large areas could be tricky. Nonetheless, the authors are excited about the research opportunities the new material will open.

"Metamaterials will potentially allow us to do many new things with light, things we don't even know about yet. I can't even imagine what all the applications might be," Garcia said. "This is a new tool kit to do things that have never been done before."