More to Remember Than Just the Madeleine

Celebrating the Centennial of Proust’s ‘Swann’s Way’

By JENNIFER SCHUESSLER

Published: November 7, 2013

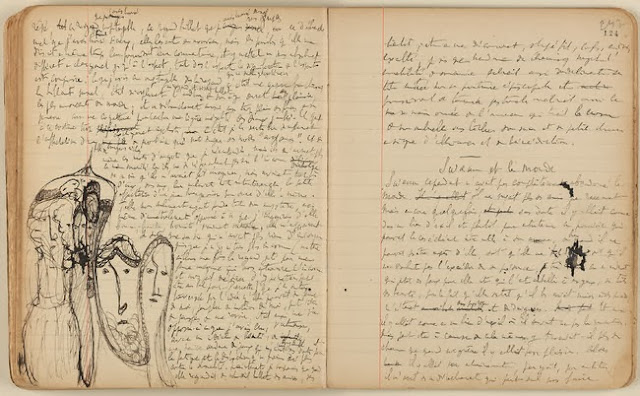

Marcel Proust's notes and doodles for "Swann's Way," published in 1913.

Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF), Paris, France, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

But in recent days, the radio host Ira Glass, the pastry chef Dominique Ansel and a crew of other long haulers have been worrying less about leg cramps than semicolons.

The marathon in question is a weeklong “nomadic reading” of Marcel Proust’s “Swann’s Way” that will celebrate the centennial of that first installment of “In Search of Lost Time” by bringing Proust’s endlessly subdividing sentences, microscopic self-consciousness and, yes, plenty of madeleines to seven Proust-appropriate locations across New York City.

In Mr. Glass’s case, that would be a bed in a room at the Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where, at 7 p.m. on Friday, he will recite the book’s opening — “For a long time, I went to bed early” — from under the covers before passing the baton, so to speak, to the next in a chain of nearly 120 readers recruited by the French Embassy’s cultural services division.

“There’s a corny literalness that I appreciate,” Mr. Glass said by telephone, before admitting that his knowledge of the book, perhaps appropriately, lay more in the realm of Proustian memory than recent experience. “Besides, when the French Embassy asks you to do something, you say yes.”

This year’s centennial has already been honored by academic conferences and an exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum, featuring manuscripts that had never before traveled outside France. But the mostly English-language nomadic reading, to be followed next weekend by a more agoraphobic-friendly 20-hour overnight event at Yale University staged inside a re-creation of Proust’s cork-lined bedroom in Paris, offers a chance for para-Proustologists, as scholars have been known to call their amateur counterparts, to get into the act.

“In France, ordinary people are more likely just to read Proust at home,” said Antonin Baudry, the cultural counselor of the French Embassy and one of the event’s organizers. “This reading is a way of showing how Proust is alive in the United States.”

It also represents a chance for the rarefied Proust, who took a half-step into the mainstream in the late 1990s with books like “The Year of Reading Proust” and “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” to grab some pop-culture market share from the perennial marathon-reading favorite, “Ulysses.”

Sure, Bloomsday has the Guinness. But the nomadic reading will have madeleines baked by Mr. Ansel (better known as the inventor of the Cronut) and a deep bench of partisans eager to plump for the more intimate pleasures of Proust.

“As a young writer, I felt there were two kinds of people: Joyce people and Proust people,” said the novelist Rick Moody, a utility infielder who has also participated in “On the Road,” “Lolita” and “Moby-Dick” marathon readings. “For a long time, I would’ve asserted my allegiance to Joycean qualities. But in my galloping middle age, Proust calls to me more fervently.”

For those lacking the stamina to take in every word of “Swann’s Way” at a gulp, shortcuts are available. Harold Pinter’s unfilmed 1972 “Proust Screenplay,” which boils down all seven volumes of “In Search of Lost Time” to about three hours, will have its first American hearing at a staged reading at the 92nd Street Y in January. If that’s still too long, the classic Monty Python “All-England Summarize Proust Competition” skit is waiting on YouTube.

But for many, the appeal of Proust is precisely that he forces readers to slow down and pay attention. “Proust is a cure for attention deficit,” said Alice Kaplan, the chairwoman of Yale’s French department and an organizer of the reading there. “You just cannot hurry through those sentences.”

Mass readings of “Remembrance of Things Past” (as some partisans of C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation still call Proust’s novel) are not an exclusively American phenomenon. Since 1993, for the project “Proust Lu” (“Proust Read”), the French filmmaker Véronique Aubouy has shot over 100 hours of more than a thousand ordinary people reading the work sentence by sentence, while sitting on top of a tractor, wading in a lake or standing in a hat shop — and she’s only partway through Volume 4.

But in the United States the embrace of the difficult and very French Proust may be a way of asserting one’s allegiance to the madeleine over the freedom fry.

“People here are eager to pull out whatever Proust credentials they have,” said Caroline Weber, a professor of French at Barnard College who is working on a book about three real-life aristocratic women who inspired Proust’s characters. “But in France, Proust doesn’t have that special significance as cultural shorthand. He’s French, and so are they.”

American Proustmania can lead to some awkward cross-cultural moments. Harold Augenbraum, founder of the Proust Society of America and a participant in the nomadic reading, recalled the startled reaction he got a few years ago from the attendant at an Art Nouveau pissoir under Paris’s Place de la Madeleine when he asked if he could lead a tour group of American Proustians in an impromptu reading of a scene in which the moldy smell of another urinal awakens a particularly pungent memory.

“She looked at me like I was out of my mind,” Mr. Augenbraum said. “But that was part of the idea, to make it comic for everyone.”

There may be similarly puzzled reactions at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx on Sunday, should unsuspecting visitors happen upon students from the Lycée Français and the French American School of New York who will be reading (presumably more wholesome) passages in a patch of forest, chosen to represent young Marcel’s paeans to the countryside.

The Yale reading, by contrast, will emphasize Proust’s asthmatic, indoor spirit, though a team of students from Yale’s drama school has been offering coaching sessions to help the 100-plus participants avoid becoming stuck in syntactic dead ends, to say nothing of actual respiratory attacks. “His sentences are completely energetic, and you are completely out of breath reading him,” Ms. Kaplan said. “It’s the asthmatic teaching us breath control.”

Ms. Weber will be reading on Monday at the Oracle Club, a private arts space in Long Island City, Queens, meant to evoke the grand salons Proust frequented before illnesses real and imagined consigned him to bed.

“Maybe I’ll wear a fur coat indoors, and bring my maid and instruct her to run around at various points and open windows,” Ms. Weber said. “Proust would send really funny letters to hostesses saying, ‘I’ll come, but can only come after 11, and only if you open all the windows, then close them when I get there.’ He had all kinds of Mariah Carey-in-the-green-room stipulations. It might be amusing to put on that kind of show.”

Reading Proust: An Introduction

By SAM TANENHAUS

One hundred years after its publication, “Swann’s Way,” the first volume in Marcel Proust’s cycle “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu” — “In Search of Lost Time,” better known to many Anglophone readers as “Remembrance of Things Past,” the Shakespearian title used by Proust’s first English translator — doubles as thematic “overture” and Michelin guide to the most captivating, ambitious and elusive of modern novels.

The glittering surface of “Swann's Way” presents a Manet-like canvas of belle époque France, a sumptuous world of fashionable salons and tranquil summer homes populated by characters — old and young, rich and poor, artists and aristocrats, footmen and physicians — who spring at us with comic ferocity: their sufferings and delusions, their petty cruelties, their self-destructive obsessions and corrosive vanities. By the end of the giant cycle (some 4,000 pages) these fictitious beings will seem realer than the members of one’s own family.

But within the space of far fewer pages, 200 or so, the reader grasps, just as readers did in 1913, that Proust is a novelist of limitless talent: a preternatural observer, inspired mimic, prodigious wit, fluent narrator, ingenious coiner of images and words. And he knows everything, sounding at times like a botanist, at others like a painter, architectural historian, musicologist, literary theorist. He seems to have read every book, seen every play, and absorbed the contents of entire museums along with the principles of medicine, diplomacy, etymology and more.

Yet all this only touches the outskirts of Proust’s herculean purpose. As the sinuous sentences unfold, aphorism following insight, metaphor converted into syllogism, we realize Proust is as rigorous a thinker as he is fabulist, heir to Descartes, companion to Freud. He is not “simply” writing a novel. He is bending the girders of an inherited form into a new science of understanding. He means to unlock the “laws” of human psychology — of hidden motive, desire and crippling habit — and so perhaps arrest, if not defeat, the ravages of “Time.”

We know this is his intent because he frankly tells us so. The novel’s narrator addresses us with the brazen directness of our own moment’s memoirists, though Proust is strangely self-effacing, even his terrifying omniscience grounded in his repeated insistence that he really knows nothing at all.

Inevitably, the first pages of “Swann’s Way” announce that the grand investigation to come must be autobiographical and must begin in childhood, for the impressions gleaned then will determine a lifetime of tiny misconstruals and fatal miscalculations, of revelations that would not surprise us, and they do each time, if only Proust, and we, had been paying closer attention.

These first pages also set forth Proust’s theory of “involuntary memory,” encapsulated in the famous incident of the madeleine soaked in tea. When the narrator presses the spoon to his lips, the sensation looses a tactile flood that transports him to the past — not the known but the latent or repressed past, hitherto concealed from him by the organized recollections of “voluntary” or conscious memory, the prison of falsehood each of us constructs in the effort, we think, to uncover the truth, though in fact it only makes it more elusive. Not that “involuntary memory,” the morsel of tasted cake, makes Proust the master of reality. On the contrary, he is allotted only flickering glimpses, which will accost him unpredictably and, often, woundingly.

“Swann’s Way” and the six novels that follow can be read as the mounting sequence of these glimpses. Everything else, in the rich and varied universe Proust has invented, exists only as the stage for these scattered lightning-flashes. The most cerebral of writers, Proust seeks finally to free himself, and us, from the shackles of intellect and reason.

NOMADIC READING Friday to Thursday; various locations in New York; frenchculture.org.

THE YALE PROUST MARATHON Nov. 16 to 17; New Haven; proustatyale.com.

ON PROUST Panel with William C. Carter, Jennifer Egan, Laurent Mauvignier and Olivier Rolin; Nov. 17, 11 a.m.; 92nd Street Y, 1395 Lexington Avenue; 92y.org.

REWRITING PROUST Panel with authors. Nov. 19, 7 p.m.; Center for Fiction, 17 East 47th Street, Manhattan; centerforfiction.org.

PINTER/PROUST Jan. 16; 92nd Street Y; 92y.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment